Bone health is a critical aspect of overall wellbeing, particularly as the population ages. It’s also become a significant public health concern, with osteoporosis and related fractures forecast to substantially increase over the next decade.

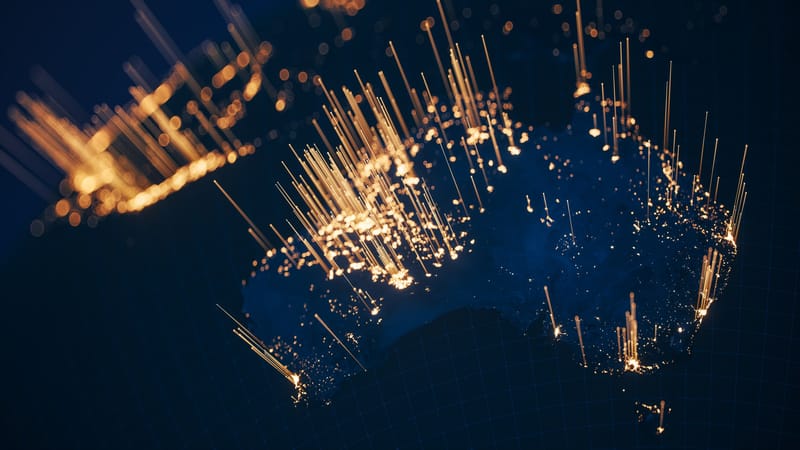

Approximately 6.2 million Australians over 50 are living with poor bone health, including conditions such as osteoporosis and osteopenia. This number is projected to increase by 23% over the next decade, reaching 7.7 million by 2033.

Osteoporosis, characterised by weakened bones and an increased risk of fractures, is particularly prevalent among older adults. However, it can affect individuals of all ages, especially those with risk factors such as a family history of the disease, low body weight, or prolonged use of certain medications.

Fractures are a common consequence of poor bone health. In 2023, Australia recorded a fracture every 2.7 minutes, amounting to more than 193,000 fractures annually. This rate, too, is expected to worsen, with projections indicating a fracture every 30 seconds by 2033.

The economic burden of osteoporosis and osteopenia is also significant, with costs estimated to rise from $4.8 billion in 2023 to $8.3 billion by 2033.

The most common fractures associated with osteoporosis are hip, spine, and wrist fractures. Hip fractures, in particular, are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. They often require surgical intervention, and can lead to long-term disability and loss of independence.

Advances in treating fractures

The management of fractures has seen significant advancements in recent years, driven by improvements in surgical techniques, technology, and rehabilitation practices.

While many fractures heal without complications, some do not. Some common problems associated with broken bones and their healing process include nonunion and malunion, infection, post-traumatic arthritis, and bone deformity.

How our body heals a bone fracture.

Soon after a fracture occurs, the body forms a protective blood clot and callus around the fracture. New “threads” of bone cells start to grow on both sides of the fracture line and towards each other. pic.twitter.com/ux5T3pTWEW— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) October 11, 2023

Despite these challenges, the advances in medical technology and treatment methods have significantly improved the outcomes for people with fractures.

Now, a Monash University research team is confident it can further transform how broken bones are treated, with the development of a special zinc-based dissolvable material that could replace the metal plates and screws typically used to hold fractured bones together.

Surgeons routinely use stainless steel or titanium, which stays in the body forever, can cause discomfort, and may require follow-up surgeries.

But the new zinc alloy, designed by Monash biomedical engineers, could solve these problems by being mechanically strong but gentle enough to degrade safely over time while supporting optimal healing.

A study recently published in Nature describes the research team’s innovative approach that makes the zinc alloy as strong as permanent steel implants, and more durable than other biodegradable options such as magnesium-based implants.

Lead researcher Professor Jianfeng Nie, from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, said the material had the potential to transform orthopaedic care by reducing complications, minimising the need for additional surgeries, and offering a sustainable alternative to permanent metallic implants.

“Our zinc alloy material could revolutionise orthopaedic care, opening the door to safer, smaller implants that not only enhance patient comfort, but also promote better healing outcomes by minimising disruption to surrounding tissues,” Professor Nie said.

“An implant that never disappears will always be a risk to the patient. On the other hand, one that degrades too fast won’t allow adequate time for the bones to heal. With our zinc alloy material, we can achieve the optimal balance between strength and controlled degradation of the implant to promote better healing.”

The research shows that by engineering the size and orientation of the material’s grains, the zinc alloy can bend and adapt in unique ways to accommodate the shapes of its neighbouring tissues.

“This made it not only stronger but more flexible, offering a game-changing alternative for orthopaedics,” Professor Nie said.

The research is paving the way for a startup to be launched out of Monash University with a focus on developing next-generation biodegradable implants.