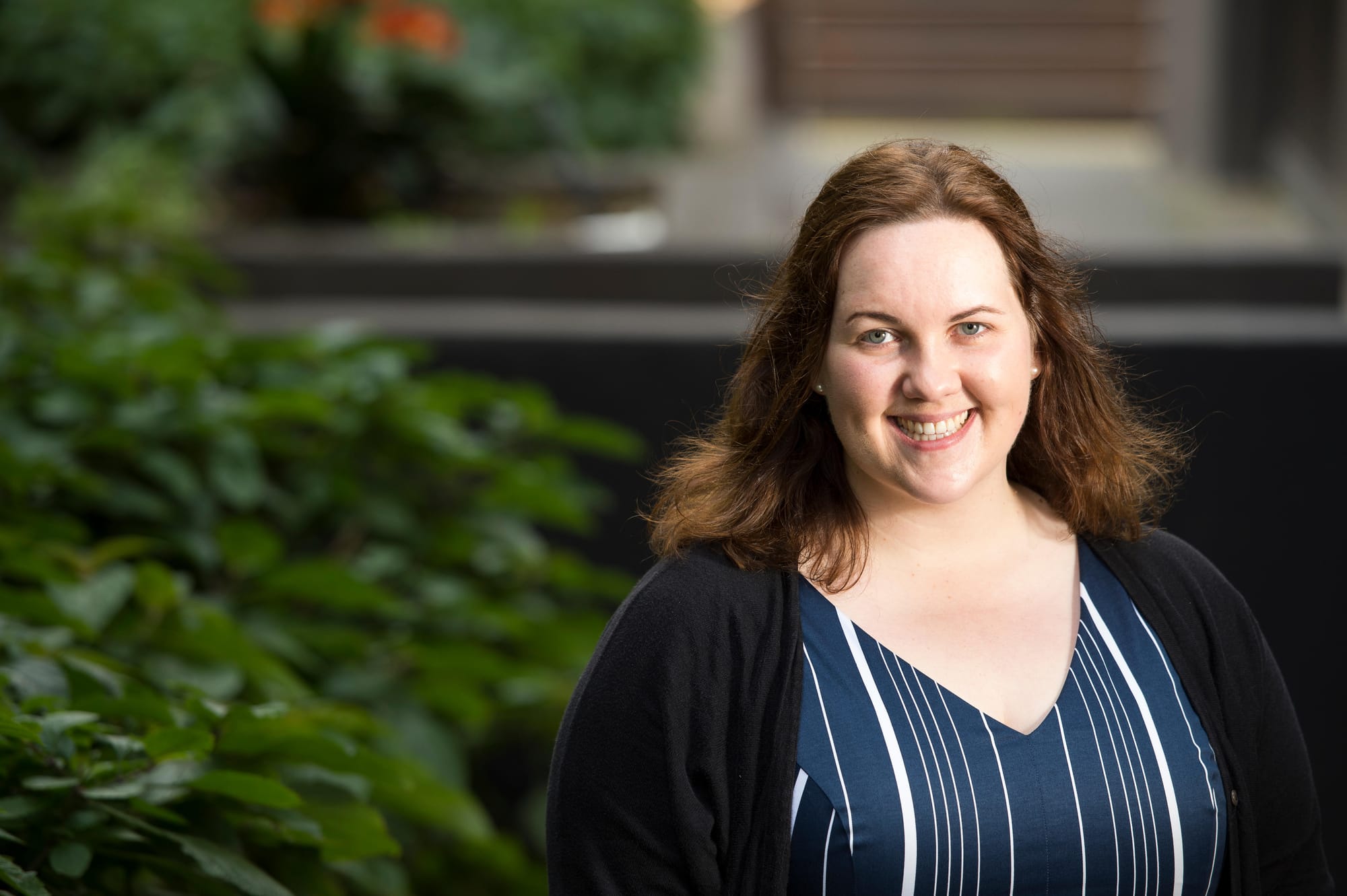

It’s difficult and confronting work, but Monash University forensic anthropologist Samantha Rowbotham knows it’s for the greater good.

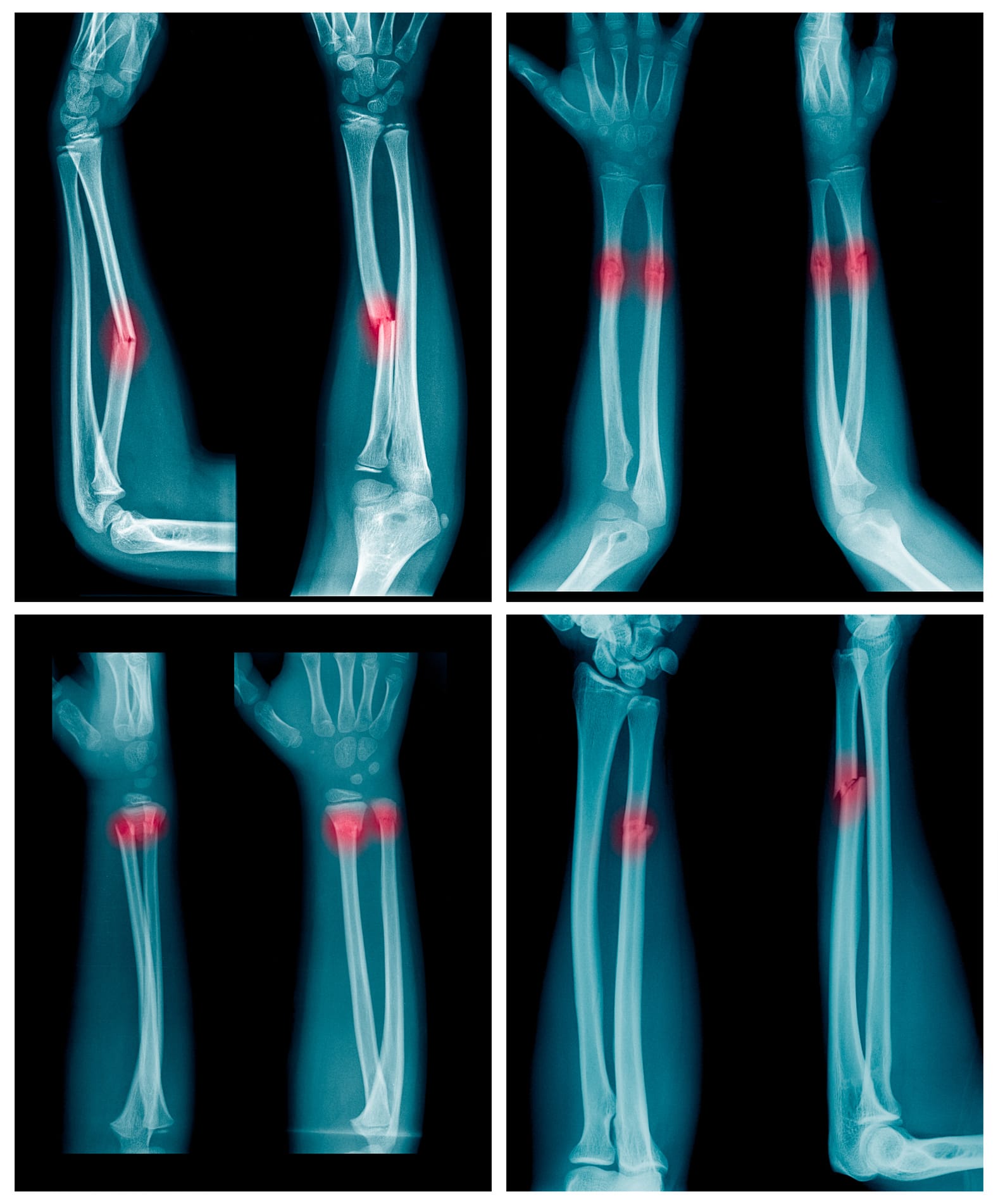

She studies skeletal trauma – that is, the broken bones of the dead. Her research is mostly all in children. Her key enquiry is investigating the difference between the bones of a child killed accidentally in a fall and a child killed by “non-accidental blunt-force trauma”, which translated to plain English means being hit, stomped on, kicked, thrown or otherwise assaulted in the context of child abuse.

The end result of her harrowing research will be that courts – mostly coroners’ courts – will be better-placed to tell the difference between the two very different sets of events. A common defence for alleged child abuse is that the injuries were caused by a fall. There is, so far, little detailed research on paediatric skeletal injuries in the medico-legal context.

But now Rowbotham has won a Victoria Fellowship from the Veski group, giving her state government money to travel to three forensic institutions overseas this year to broaden her work – she’ll visit South Africa, France and Denmark to embed herself in forensic labs. Towards the end of the year she’ll add her findings to data from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (VIFM), where she works, to begin building a world-first database.

The work is crucially important to an under-researched and ugly crime. VIFM’s senior forensic anthropologist, Associate Professor Soren Blau, says it will help courts move beyond hearsay towards facts.

“Rather than opinions about skeletal trauma presented in court being based on anecdotal findings from casework,” she says, “the results of Sam’s research set the foundation for providing a robust approach to how skeletal trauma is interpreted.”

Paediatric skeletal trauma is one of five projects (all to do with skeletal trauma, or broken bones, of some kind) Rowbotham is involved in out of the VIFM. There are 15,000 cases of physical child abuse a year in Australia, most not fatal, but “it’s an important social issue”, she says, “and these types of cases are particularly complex for medico-legal practitioners. How can we differentiate skeletal injuries that result from an accidental fall with injuries that result from physical abuse? It’s a challenging question for many reasons.”

Social impact

There's significant social/societal fallout from paediatric trauma cases – such as parents or caregivers being separated from children, if the parents are suspected but proof is scant. Or conversely, children being mistakenly left with abusive parents.

She says children’s bones are difficult to study as well; they’re different to adult bones in that they’re still developing. “The bones of a child are more elastic than an adult. So when force is applied to a child’s bones, the bones will bend before they break, unlike an adult’s bones, where they’ll simply break.

“This difference in biology means fractures appear differently in a child’s skeleton. The body proportions of a child are also different. Infants and very young children have heavier heads, so their centre of gravity is different to an adult’s, and this can influence how they land when falling,” Rowbotham says.

“The way our bones fuse and develop with age also influences where we see fractures, and how those fractures heal. It is in some ways much more complicated to look at a child’s skeleton.”

All that is apart from the daily routine of studying images of dead children’s bones.

“It’s certainly not easy, and it doesn’t seem to get any easier. But this is a contribution I’d like to make to my field,” she says.

Rowbotham trained originally as an archaeologist and biological archaeologist – she was interested in prehistoric and medieval archaeological remains. But then she decided to transfer her osteology skills to the medico-legal field. She found her niche in forensic anthropology.

“Trauma is one of the main contributions anthropologists provide to medico-legal investigations in Australia. Historically, the role of the anthropologist used to be focused on the identification of remains, but now with DNA and odontology [forensic dentistry[ we don’t do as much around the identification of an individual, but rather what happened to them around the time they died based on their injuries.”

Novel approach

Rowbotham’s method for comparing injuries and mapping the connections between them is relatively simple, but it’s a novel approach. She uses post-mortem computed tomography (PCMT) scans and coronial data to look at cases of skeletal blunt-force trauma to identify patterns of injury.

“If you see a fracture to the skull, did the child fall backwards and hit their head? Or did someone throw that child against a wall or hit them with a blunt object to the back of the head?

“If you see a fracture to the skull, did the child fall backwards and hit their head? Or did someone throw that child against a wall or hit them with a blunt object to the back of the head?"

“At the moment, it’s difficult to say which mechanism, the fall or physical abuse, caused the blunt-force trauma, because we don’t know what types of fractures and what types of fracture patterns we should see with each of those different blunt-force trauma events. This study will begin to answer those questions.

“This has always been an issue, but there’s been very little robust scientific research undertaken until now.”

Rowbotham begins collecting data from VIFM in August then travels in October and November. She’ll visit the Medico-Legal Laboratory at the University of Pretoria, the Medico-Legal Institute in Paris, and the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Forensic Medicine, and hopes to begin seeing results by the end of the year.