The Spanish flu was particularly deadly for healthy men aged between 20 and 40. It acted so swiftly that people said a young man could be well at breakfast and dead by dinner.

COVID-19, on the other hand, is devastating the elderly, and those with respiratory diseases, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Indigenous Australians have high rates of all these illnesses, which are also diseases of poverty.

Although Australia has to date successfully controlled the COVID-19 outbreak, historian Lynette Russell says she’s “terrified” of the impact a second or third wave could have on Indigenous Australians.

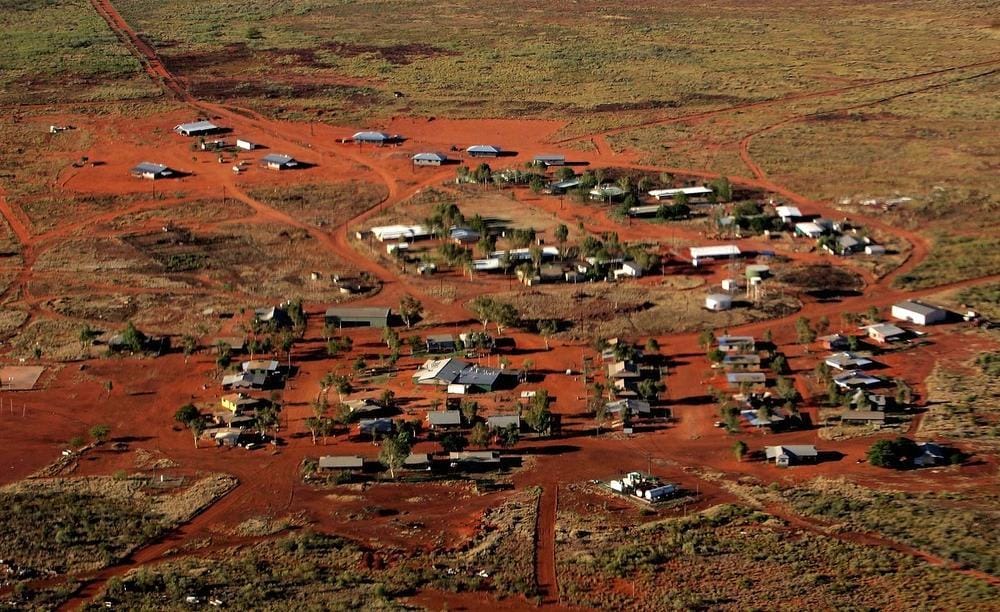

“People in very isolated or remote communities have been protected, because they have strong boundaries around them,” she says. In the Northern Territory, for instance, the military are patrolling highways to ensure that strict isolation regimes are enforced – measures supported by Indigenous communities, who themselves called for the borders to be closed. (The restrictions are due to be lifted in June.)

Indigenous communities have also created health information posters and videos about COVID-19 in Aboriginal languages for people who speak little English.

“What we're seeing is the splendid exertion of power from these communities, particularly the Aboriginal-controlled and operated health services – they’re really showing the way to protect their communities,” Professor Russell says.

But Indigenous people living in urban areas, including homeless people, remain vulnerable, she says. “People who are living on the street – it literally wakes me up at night, wondering what that must be like,” she says. “It must be terrifying.”

Spanish flu took a heavy toll

It’s little appreciated that the Spanish influenza was particularly deadly in Aboriginal communities, she says. In Barambah (now known as Cherbourg) in Queensland, for example, 596 people became infected in a community of 606. Of these, 87 died and were buried in a mass grave.

The number of Aboriginal Australians killed by the Spanish flu isn’t known. Aborigines weren’t included in the census, although Aboriginal men did serve in WWI – in one tragic instance, two Indigenous soldiers unknowingly brought back the disease to their 100-strong community of Euraba on the Queensland-NSW border, with 54 men, women and children later dying in the outbreak.

The second and third waves were even more deadly – 12,500 Australians are estimated to have died in the pandemic altogether. Research on the impact of the illness on Indigenous Queenslanders by Aboriginal historian Gordon Briscoe estimated that one third of the fatalities (or 315 people) were Indigenous.

“Some of the difficulties in determining the numbers of people that died is the way in which people were categorised,” Professor Russell says. “So the various protectors, particularly in Queensland, if they had an Aboriginal person, but that Aboriginal person had perhaps a white father, then they weren't recorded as an Aboriginal death.”

Disease, destruction, then smallpox

Professor Russell points out that at the time of the outbreak, Australia’s Aboriginal population had already been decimated by disease, bullets, and the effects of losing their land and traditional way of life. From the time of the First Fleet, communicable diseases devastated Indigenous people along the east coast; one particularly virulent disease was smallpox.

Early explorers and, later, observers estimated that the first wave of smallpox reduced Aboriginal communities by half. “We had several waves of smallpox, but also waves of influenza, measles, and other diseases that Europeans had built immunity to over generations,” Professor Russell says.

"For the most part, this pandemic is very much being depicted as something that is affecting all of Australia equally, but we know that it's not.”

Melbourne saw two smallpox epidemics – the first struck around 1788-89, probably travelling into Victoria through the river system. The second wave took place around 1829.

In 1835, “when John Batman and his group arrived, there were 15 to 16,000 Aboriginal people in Victoria,” she says. “And it's probably a quarter of what was here just a generation earlier – 45,000 people had disappeared.” Then colonisation took its toll. By 1850, only 1900 Aboriginal people were recorded as having survived.

Combating the negative depiction

The shocking impacts of disease and dispossession led to what Professor Russell calls “the early 20th-century extinction discourse”, the insidious belief that Indigenous people were doomed because they were intrinsically weaker. She’s concerned that COVID-19 will revive this discourse, and “I think that we have to resist that really negative depiction”.

In the US, poor black communities have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19; she’s afraid that a similar scenario could take place in Australia.

So far, the Australian government has responded “brilliantly” to the health emergency, she says. But she adds “for the most part, this pandemic is very much being depicted as something that is affecting all of Australia equally, but we know that it's not”.

We know, for example, that “the experts tell us disease will be very bad for anybody over the age of 70 or over the age of 50 if you're Indigenous,” she says. “We need to be very cautious, though, that these models are not implying that Indigenous people are more at risk, as a lot of those things are the result of co-morbid health issues, which are caused by poverty.”