This year marks the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s encounter with the great southern continent and its original occupants.

After claiming the eastern coast for the British crown, Cook observed in his journal “so far as we know [it] doth not produce any one thing that can become an Article in trade to invite Europeans to fix a settlement upon it”.

Unbeknown to Cook, Aboriginal Australians had been interacting with explorers and traders for centuries, historian Lynette Russell says. She wants to challenge the conventional view that they were an isolated and passive people, stranded on a lonely continent.

“It’s not a long period of Aboriginal people being here all on their own and then suddenly Cook bumps into the east coast, and everything is different,” she says. “Australian history is far more complex.”

Professor Russell has received a $2.94 million Australian Research Council Laureate Fellowship to explore the relationships forged between Indigenous Australians and outsider cultures in the millennium before Cook arrived.

"Global Encounters and First Nations Peoples: 1000 Years of Australian History" will examine interactions with the Dutch, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the French, and the Makassans from Indonesia.

Three postdoctoral fellows are working with Professor Russell on the project, one examining the Makassan archives, one the Dutch, and one investigating Aboriginal people’s responses to these newcomers.

“We’re looking at multiple strands of evidence – language, Dreamtime stories, Indigenous narratives about these events,” Professor Russell says. The researchers will also examine archives in Spain, Portugal and South Africa.

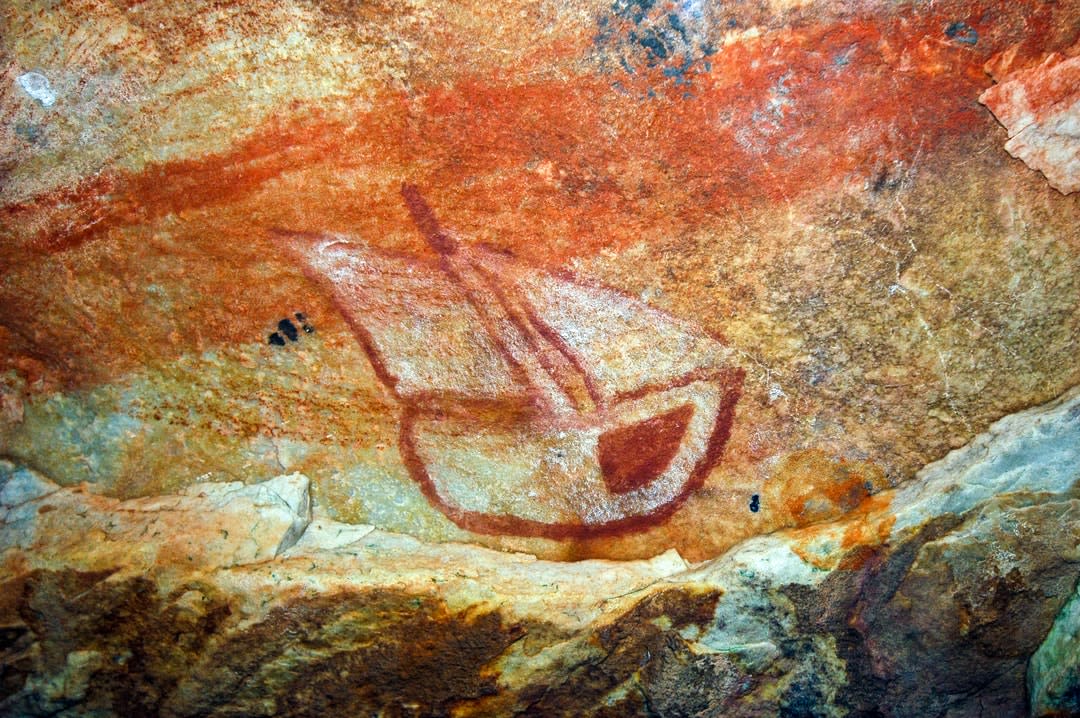

Rock art points to early contact

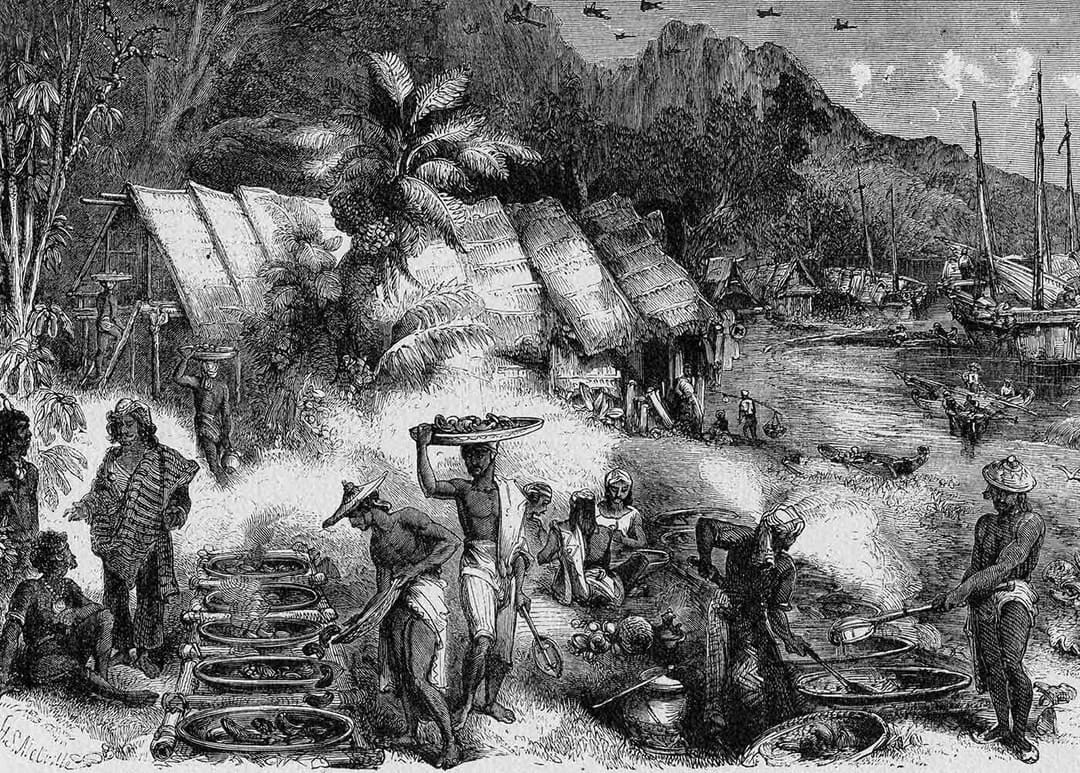

Rock art from Arnhem Land suggests the Makassans may have begun visiting Australia as early as the 1500s, she says. The Makassans, who also visited the Kimberley, came for trepang, or sea cucumbers, arriving with the northwest monsoon each December, and living with Indigenous communities for about four months.

After boiling and drying the trepang on Australian beaches, the Makassans returned home and traded their harvest with the Chinese.

“I’d love to include China in the project, too,” Professor Russell says, “but I think it might be impossible at this point. There are some odd finds here and there, a bit of Chinese ceramic in a midden site in Torres Strait, or there’s some Chinese coins found along a beach.”

Many tantalising hints of Indigenous interactions with foreign cultures in the days before Cook have never been properly investigated, she says, but they deserve to be.

“The Chinese coins, for instance, could easily be explained away as items dropped by someone in the 1950s who had them as a souvenir. That’s possible. In this project I want to synthesise all the strange and unusual things that we hear about from time to time.”

An enduring relationship

The Makassan contact with the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land was intimate and long-lasting, Professor Russell says.

“Yolngu people will tell you that they have family in Makassar. And Makassan people will say they have family in northern Australia. There’s very significant linguistic relationships, too – quite a number of shared terms.”

The tamarind and peppercorn trees on the north coast are further signs of Makassan influence. Last year, a Yolngu woman mentioned to Professor Russell “she had some Islamic coins” that had been passed down through the family, which almost certainly had come in through the Makassans.

Indigenous rock art from the Top End depicts sailing ships and guns, most likely from Dutch and Portuguese expeditions.

The Dutch were the earliest-known Europeans to explore Australia. Their presence was first documented in 1606. (The Spanish explorer, Luis Vaez de Torres, is believed to have passed the northern tip of Cape York in the same year, while navigating Torres Strait.)

The Dutch East India Company was based in Batavia – now Jakarta – where it traded in spices.

“In a sense, it was the world’s first transnational company,” Professor Russell says. Company ships “bumped into Australia on more than one occasion”. Archives in Holland and South Africa will be examined for information about the company’s southern explorations.

The Dutch also visited the Kimberley coast, the islands of the Dampier Archipelago (named after British privateer and explorer William Dampier, who visited in 1699).

In 1656, a Dutch East India Company ship, the Vergulde Draeck (Gilt Dragon), sank after striking a reef near Ledge Point, about 100 kilometres north of Perth. Captain Pieter Albertszoon stayed behind with 75 survivors, dispatching a small crew to Batavia for help. A further 11 men were lost in subsequent rescue missions, and the original 75 were never found.

But in 1931, 40 silver coins were uncovered in the sand hills north of Cape Leschenault. Thirty-two years later, in 1963, the Vergulde Draeck’s remains were identified off the nearby coast. The ship was travelling from South Africa to Batavia; an elephant tusk was found in the wreck.

What happened to the survivors?

Professor Russell says she's seeking help from medical scientists to explore why a group of West Australian Indigenous people would share the same rare genetic mutation as members of the Amish in Pennsylvania. “It might be a random mutation,” she says. Or it could indicate blood ties with the Dutch.

Collecting Indigenous stories

Professor Russell and her team will also collect Indigenous stories from around the coast. A Tasmanian story, for example, describes “a great floating island”, which could be their account of a French ship, she says. And an Indigenous story from Queensland’s Fraser Island tells of “a great bird that came flying across the ocean” – this is a Portuguese or French ship, she believes. The story is thought to date from before Cook’s arrival.

Possible Polynesian connections will also be investigated. The trade winds blow from west to east, and have been cited as a reason why Australia’s eastern seaboard wasn't explored earlier. But Polynesian objects have been found in Queensland, and their origins remain unexplained. “They've never been properly analysed,” Professor Russell says, “and it's worth doing.”

Melanesian contacts with Australia have taken place over 3000 years, she says. They'll be excluded from her research, because the wide range of interactions “would explode the project”.

“I’m trying to look at outsiders,” she says. “And while one might imagine Melanesians to be outsiders, there’s so many connections. If you look at Torres Strait, there’s a gradation from Melanesia into Australia.”

Professor Russell hopes her research will broaden our understanding of how Indigenous Australians responded with creativity and curiosity to their many foreign visitors. The story has never been told.

“A key part of every single piece of research I've ever done is to show Indigenous agency,” she says. “I don’t want to present Aboriginal people and, to a degree, Torres Strait Islander people as merely reactive. I want to show them as proactive.

“I have Aboriginal heritage, so I’m very passionate about the history of this country,” she says. “I think every Australian should be incredibly interested, because it's remarkable. There's nowhere on the planet like our home.”