Once again, the UNESCO World Heritage Site at Atapuerca, Spain, is offering new insights into the history of human evolution.

During our 2022 field season, we unearthed a series of bone fragments from the Sima del Elefante site, specifically from level TE7. These fragments represent the left side of an adult individual’s midface, now labeled ATE7-1.

The location of this remain, two metres below a previously discovered human mandible at TE9, suggests that ATE7-1 is older, dating to between 1.4 and 1.2 million years ago.

Since its discovery, an interdisciplinary team has dedicated more than two years meticulously studying these remains to determine which species they belonged to, as well as to understand their adaptation strategies and the environmental conditions they faced. In addition to the restorative works, we employed high-resolution mCT images and 3D models to piece the bone fragments together, allowing us to accurately reconstruct the bone structure and teeth.

Fossils reshaping understanding

The archaeopalaeontological sites in the Atapuerca hill range are located in the historic province of Burgos, on the Castilla-León plateau in Spain, just 15km from the city. This karstic complex contains more than 4km of caves filled with sediments ranging from the Early Pleistocene to the Bronze Age. Currently, more than 10 sites are being excavated, and human fossils have been recovered from six of them, dating as far back as 1.4 million years.

The fossils discovered at Atapuerca have reshaped our understanding of European hominin evolution multiple times. One of the most significant findings was the identification of H. antecessor, a species that inhabited this region about 850,000 years ago, as confirmed by direct dating of the human remains.

This discovery challenged the “short-chronology” hypothesis, which suggested Europe was only populated during the Middle Pleistocene, 500,000 years ago.

The recent discovery of a new fossil remain, ATE7-1, in the Sima del Elefante site pushes the timeline of human presence in Europe even further back.

Which species does it belong to?

To this moment, the earliest evidence of human settlement in Western Europe comes from the Atapuerca-Gran Dolina site, represented by H. antecessor species. The first question we asked was whether ATE7-1 could be assigned to H. antecessor.

One key feature of H. antecessor is its relatively modern-looking face, which is not projected as we typically picture in earlier species, but instead has a vertical morphology.

However, ATE7-1 lacks these traits, which ruled out the possibility of assigning ATE7-1 to H. antecessor. So, what species could it be?

Next, we compared the ATE7-1 remains to other earlier hominin groups, including those from the Dmanisi site (Republic of Georgia), dated to about 1.8 million years ago. Interestingly, ATE7-1 differed from the Dmanisi hominins, especially in the nasal region.

However, ATE7-1 shares some morphological similarities with H. erectus, including both African and Asian populations. These include the lack of a projecting nose and the forward-projection of the midface.

On the contrary, the ATE7-1 fossil differs from H. erectus in having a shorter and narrower face. Still, ATE7-1 is missing key features characteristic of H. erectus, so for now we are classifying ATE7-1 to H. aff. erectus, meaning that it’s closely related to this species, but lacks some of the defining morphological features.

Beyond the hominin fossils

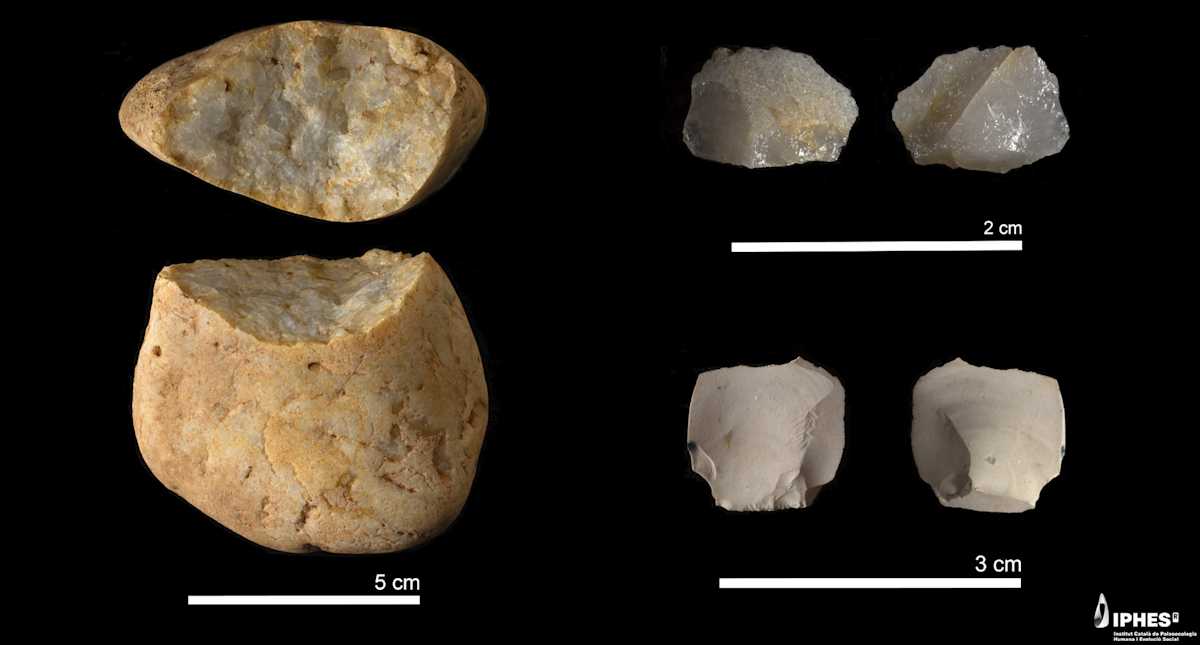

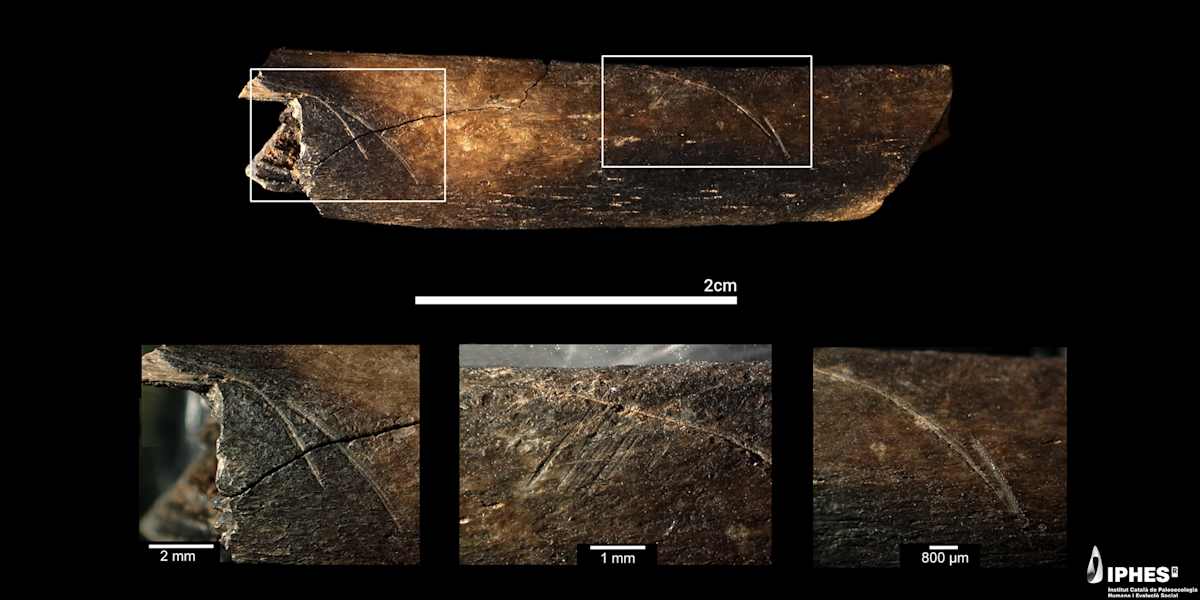

Along with the hominin fossils, faunal remains and stone tools were recovered. The marks of use on the tools, as well as the cut marks found in the faunal remains, suggest this species practiced butchery in the cave. We also know, thanks to pollen and small fauna remains, that the environment was dominated by a humid forest landscape.

This discovery opens exciting new possibilities for understanding the origins and population dynamics of the earliest human settlements in Western Europe.

The hominin fossils from Dmanisi already told us that hominins had left Africa at least 1.8 million years ago. Now, the Sima del Elefante finding tells us that within a few hundred thousand years, hominins had made it to the westernmost part of Europe, and during that time, their morphological characteristics had evolved.

Moreover, this also raises other questions about the implications of having two hominin populations in the same geographical area in such a limited timeframe. Did H. antecessor and H. aff. erectus coexist in the same area, or did they never meet, with H. aff. erectus becoming extinct by the time H. antecessor arrived? If the latter is true, what drove one species to extinction while another flourished?

In this second scenario, we need to consider the factors behind both the extinction of the species and their dispersal. Paleoclimatic and genetic evidence suggests that population dynamics could closely be linked to climate and environmental conditions. During favorable periods, hominins may have expanded into Europe, and possibly faced extinction when the climate worsened.

Finally, we must consider the possible relationship between ATE7-1, Homo antecessor, and Neanderthals within the European landscape.

There’s still much work ahead of us, but fortunately each year we return to Atapuerca to continue unearthing the evidence that pieces together the story of our origins. Each new discovery, such as ATE7-1, brings us one step closer to understanding our past.

We acknowledge all the members of the Atapuerca research team involved in the recovery and study of the archaeological and palaeontological record from Sima del Elefante site. The research of the Atapuerca sites is founding by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Regional Development Fund. Laura Martín-Francés receives support from Horizon Europe’s Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions of the EU Ninth program (2021-2027)