The pig-nosed turtle, an endangered freshwater turtle native to the Northern Territory and southern New Guinea, is unique in many respects.

Unlike most freshwater turtles, it’s almost completely adapted to life in water. It has paddle-like flippers similar to sea turtles, a snorkel-like “pig-nose” to help it breathe while staying submerged, and eggs that will only hatch when exposed to the waters of the wet season.

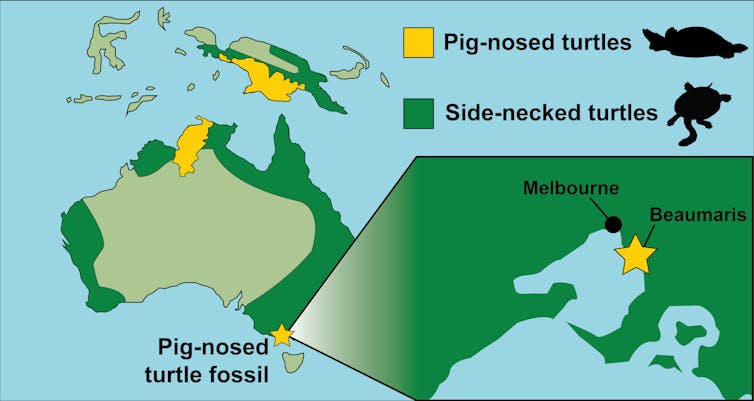

It’s also the last surviving species of a group of tropical turtles called the carettochelyids, which once lived throughout the northern hemisphere. Scientists thought pig-nosed turtles only arrived at Australia within the past few millennia, as no pig-nosed turtle fossils had ever been found here – or so we thought.

A five-million-year-old fossil from Museums Victoria’s collections has now completely rewritten this story. Discovered at Beaumaris, 20km southeast of Melbourne, this fossil lay unidentified in Melbourne Museum’s collection for almost 100 years until our team came across it.

We identified the fossil as a small section of the front of a pig-nosed turtle’s shell, as we report this week in the journal Papers in Palaeontology. Although the fossil is just a fragment, we were lucky it was from a very diagnostic area of the shell.

The fossil shows that carettochelyid turtles have been living in Australia for millions of years. But what was a pig-nosed turtle doing in Beaumaris five million years ago, thousands of kilometres from their modern range?

Well, in the past, Melbourne’s weather was a lot warmer and wetter that it is now. It was more akin to the tropical conditions in which these turtles live today.

In fact, this isn’t the first prehistoric tropical species discovered here – monk seals, which today live in Hawaii and the Mediterranean, and dugongs also once lived in what is now Beaumaris.

Read more: New seal fossil discoveries are rewriting our understanding of ancient monachine species

A tropical Melbourne?

Millions of years ago, Australia’s eastern seaboard was a tropical turtle hotspot. The warmer and wetter environment would have been perfect for supporting a greater diversity of turtles in the past. This is in stark contrast to modern times; today, Australia is mostly home to the side-necked turtles.

Tropical turtles would have had to cross thousands of kilometres of ocean to get here. But this is not unusual – small animals often cross the sea by hitching a ride on vegetation rafts.

So where are these turtles now? Why is the modern pig-nosed turtle the last remaining species of the carettochelyids?

Well, just like today, animals in the past were threatened by climate change. When Australasia’s climate became cooler and drier after the ice ages, all the tropical turtles went extinct, except for the pig-nosed turtle in the Northern Territory and New Guinea.

This also suggests the modern pig-nosed turtle, already endangered, is under threat from human-driven climate change. These turtles are very sensitive to their environment, and without rain their eggs cannot hatch.

This is true of many of Australia’s native animals and plants. In reptile species such as turtles and crocodiles, sex can be determined by the temperature at which eggs are incubated. This is yet another factor that could put these species at risk as the climate changes.

The treasure trove of fossils from Beaumaris shows just how important Australia’s previously tropical environment was for ancient animals. Southern Australia used to be home to many tropical species that now have much more restricted ranges.

Just last year, the discovery of tropical monk seals fossils at Beaumaris completely changed how scientists thought seals evolved. This shows just how much we still have to learn about Australia’s prehistoric past, when it was so different from the sunburnt country we know today.

James Patrick Rule receives funding from an Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP180101797). Museums Victoria receives support for research on The Lost World of Bayside from Bayside City Council, Community Bank Sandringham, Beaumaris Motor Yacht Squadron, Bayside Earth Sciences Society, Sandringham Foreshore Association, and generous community donations to Museums Victoria.

William Parker receives funding from an Australian Government RTP Stipend and a Museums Victoria-Monash University Robert Blackwood Scholarship.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.