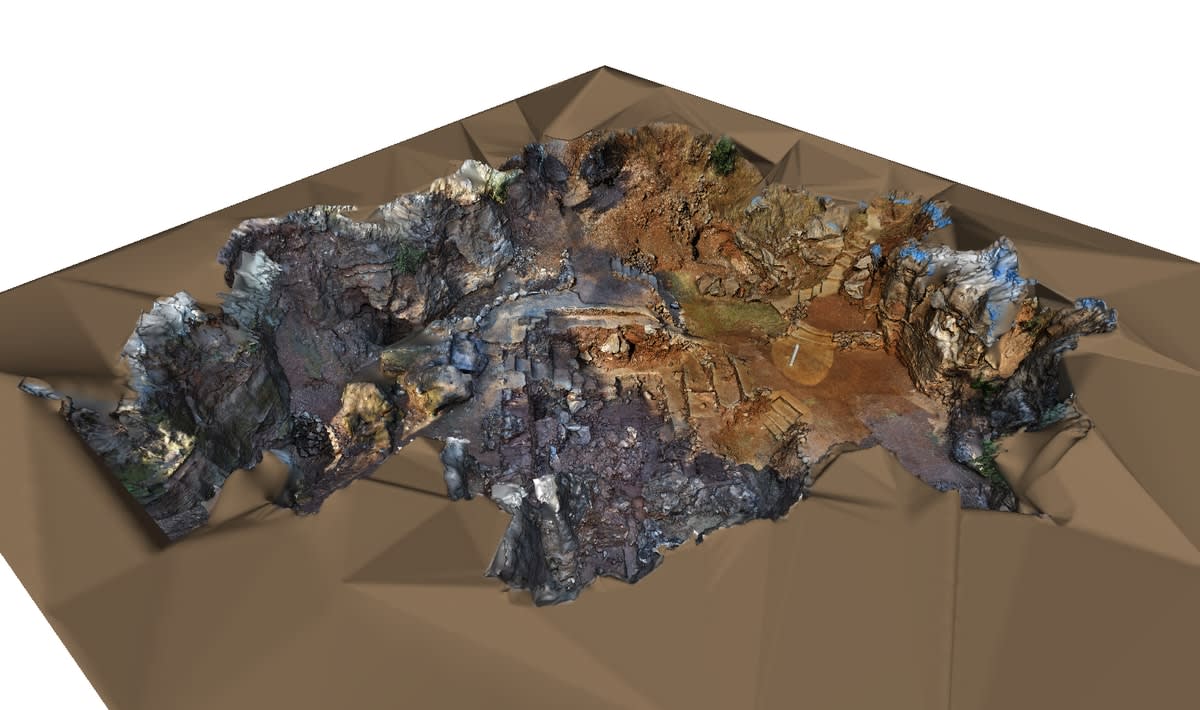

The site of the incredible discovery, explains Monash University palaeontologist Dr Justin Adams, is dry, scrubby and exposed country just 40 kilometres north of Johannesburg, in South Africa. It doesn’t look like an archetypal dig. Instead, it’s in a very old collapsed cave complex named Drimolen, within the so-called “Cradle of Humankind”.

“These are fascinating places to work in,” Dr Adams says. “In South African cave palaeontology, we don’t struggle with finding the fossils. We know where they are – they’re in the caves’ deposits, because caves attract animals.

“The caves can be water catchments in an increasingly arid environment, because they meet the underground water table. Caves also help with thermo-regulation, because it’s cold at night and hot in the day; the caves clustered and trapped body heat. We also know predators used the caves, too, to den in, or as a retreat to feed and drag animal remains in with them.”

Dr Adams is part of an international team – led by La Trobe University in Melbourne – that discovered and analysed fragments from a human-like child’s skull at Drimolen. Dr Adams is a senior lecturer in anatomy and developmental biology in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, and a field palaeontologist.

The child was aged three; the fragments are two million years old. In doing so, the team has played an integral part in solving part of the puzzle of our human origins, and have had its extraordinary findings published in the journal Science.

The three-year-old was in the group of our human ancestors known as Homo erectus. Remains of Homo erectus fossils are rare in southern Africa; most discoveries of the species have come from northern and eastern Africa, Java, China, and the Republic of Georgia.

A treasure trove of discoveries

The discovery at Drimolen not only firmly establishes the species in southern Africa, but also represents the earliest fossil specimen of the species at slightly more than two million years old.

Of equal interest to science, however, is that the discovery at Drimolen also establishes the simultaneous occurrence of three genera of early human ancestors in southern Africa, alongside an incredible diversity of other animal species.

“It’s not what I would necessarily call a controversial finding,” says Dr Adams (although this long-read in The Age/Sydney Morning Herald suggests it could be). “But it provides clarity on some major issues that have remained queries for the last couple of decades.”

The discovery proves three species of human ancestors lived in the same place at the same time, overlapping in the evolutionary chronology of our lineage. Of the three ancestral groups – Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo – only our genus (Homo) would survive past about 1.5 million years ago, and eventually lead to us – Homo sapiens (the “wise men” in Latin) – about 300,000 years ago.

We’re now the only human species on Earth, but the Science paper documents that this wasn’t always the case.

The South African site was only discovered as a palaeontological goldmine in 1992, and is now part of the UNESCO World Heritage-protected region of the Cradle of Humankind that spans across northern South Africa.

“Our discovery is planting a flag, and saying there was Homo erectus here several hundred thousand years before what was known. So whatever biological events had to take place to get us to a Homo-like condition had already happened before two million years ago.

“The discovery also ties into larger ideas we’ve had for a while about South Africa acting as an ecological refuge. It was a weird, mixed meeting point of older animal lineages starting to die out, but the newer animal lineages were migrating into these areas. There was never clear evidence for this, only suggestions that the process was occurring.

“Around two million years ago was a radical transformation in the landscape, but it had an overlap of these three separate genera [kinds] of hominins [human-like species] at the same time. They were all able to live in this landscape, but they may have been doing fundamentally different things.

“Our discovery is planting a flag, and saying there was Homo erectus here several hundred thousand years before what was known. So whatever biological events had to take place to get us to a Homo-like condition had already happened before two million years ago."

“The new kid on the block, Homo erectus, is somehow able to live on the landscape, too, and the primary adaptation is having a big brain and children with big brains.

“This new kid on the block is starting down an evolutionary pathway, but at the same time living on a marginal environment that represented a challenge for other hominin groups like Australopithecus, who we previously demonstrated had a unique survival strategy of returning to breastfeeding at times of limited nutritional options.”

Among the rich record of extinct animals from Drimolen were also fossils of two species of sabre-tooth cats that had never before been found in the same fossil deposits.

The Drimolen cave had previously been mined for lime, leaving bands of sediment full of bones and fossils. The child’s skull fragments were found preserved in these sediments.