As our understanding of sex and gender is changing, the language of healthcare is failing to keep up.

Healthcare education, settings and professionals are all struggling to describe bodies outside gendered terms. As one of the cornerstones of medicine, anatomy is facing an increasing need to find terminology that accurately reflects the bodies it represents.

Anatomical sex terminology changes over time

A look through anatomical history suggests the body is a culturally determined representation, not the foundation, of gender. In Making Sex, Thomas Laquer argues that early interpretations of the body were based on a “one-sex” model.

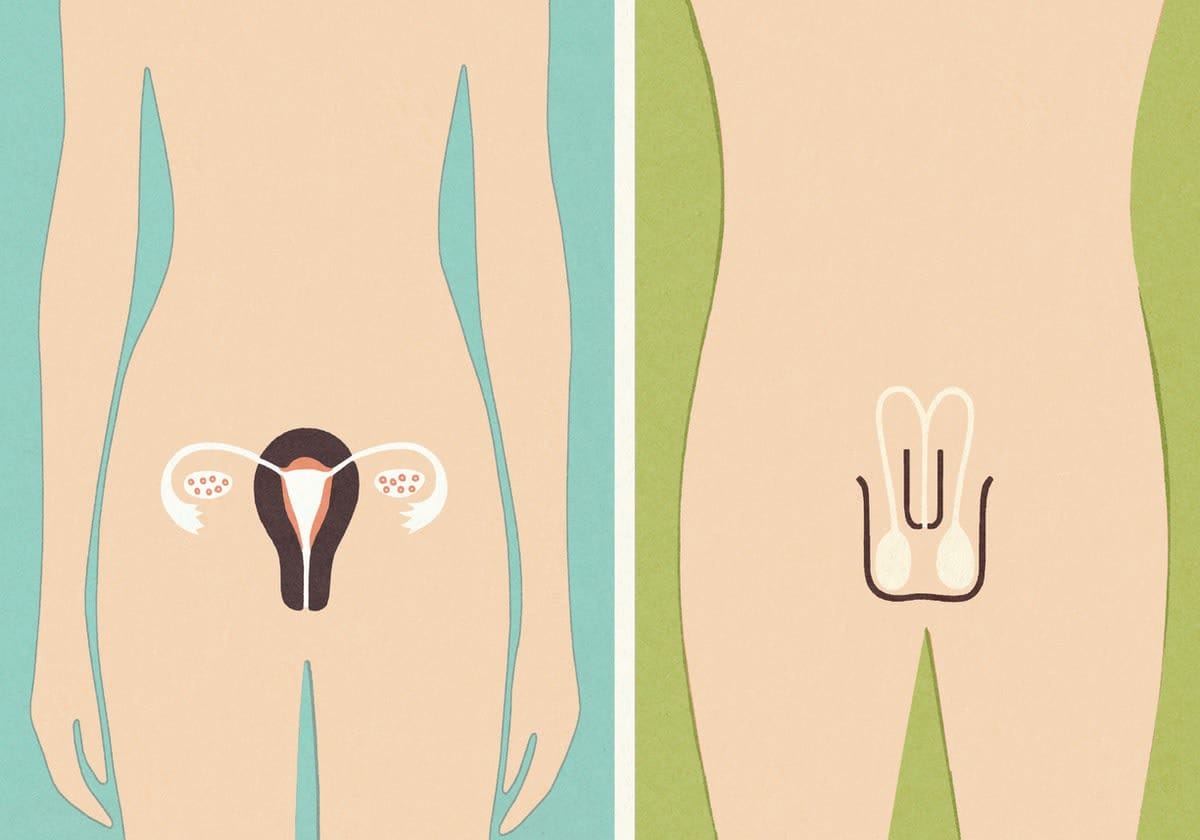

Early anatomists saw the vagina as an interior variation of the penis, and similarly, the uterus was taken to be an inversion of the testes.

Anatomical language reflected this one-sex view, with terminology only representing male genitalia. In our early understanding of anatomy, “female” anatomy was not represented at all.

As perceptions and culture changed, so did our interpretation of the body. Following the Enlightenment, our modern “two-sex” model of anatomy became more prevalent.

Anatomical terminology started to differentiate between “male” and “female” structures and bodies, often reinforcing their differing social roles. The capacity to reproduce and bear children was taken to be the basis of the female sex, and thus “biological proof” of women’s role in domestic duties.

What science says about reproductive structures

“Sex”, originating from Latin, means “to divide or cut”, and began to represent dichotomous anatomical structures such as genitalia, reproductive organs and other sexual characteristics such as breasts and body hair.

The representation of the term “gender” is, ironically, more fluid. While once synonymous with sex, this term now represents a socially constructed understanding of “masculine” and “feminine”.

Sex and gender are often communicated as “scientific facts”, yet the history and science behind this isn’t as black and white (ahem, binary) as our language implies.

An AskAnatomist podcast episode that explores the science behind sex determinisation explains that while binary genital representation is common, variation of these structures is expected and represented in populations.

A healthy individual may have labia, a clitoris, vagina and testis. In the past, these combinations of anatomical structures were viewed as a medical condition that needed to be “fixed”.

Increasingly, there’s acceptance that these structures are simply representative of the anatomical spectrum resulting from the sheer number of steps involved in human development.

The role of anatomical terminology in communication

Changes to the anatomical language aren’t new. As anatomical terminology evolved, the medical profession began struggling with communicating knowledge and innovations across the field; translations and interpretations of the local anatomy vernacular were often distorted.

A solution to this was international standards and recommendations for a globally-shared anatomical language.

Modern challenges with anatomical language do, however, persist. Controversy around eponym usage (a practice of naming anatomy after oneself) stems from both the non-descriptive nature of these terms and the misogynist undercurrents linked with this practice.

Take the eponymous “Duct of Santorini”. It may be clear that this refers to a duct, but the anatomical location remains a mystery. The Latin/English terms are very descriptive: ductus pancreaticus accessories/accessory pancreatic duct.

Furthermore, nearly all eponyms are named after identified males. A recent blog states, “... there is ALWAYS an alternative to the dead man’s name for body parts”, and the comedian Hannah Gadsby, in a hilarious clip, is seen highlighting the irony of naming anatomy related to the uterus after one such dead man.

Without representative anatomical terms, we risk miscommunication, challenges in information-sharing, and ultimately barriers to patient care where language precision is required.

Terms such as “male” and “female” pelvis, for example, illustrate the imprecision of gendered anatomy. This binary nomenclature distorts true pelvic anatomy, which is categorised across four general shapes (gynecoid, platypelloid, android, anthropoid), with individual pelvises a variation of these.

Together, these naming challenges are a call for the next anatomy language evolution.

More than just words

Anatomists are in the unique position of training the next generation of healthcare practitioners. As the language of doctors, anatomical terms influence healthcare culture.

Our current practice of using gendered structural language is misleading, confusing, and doesn’t support a culture of healthcare inclusivity. Because of this, both anatomists and doctors are calling for an expanded anatomical language.

While at face value, anatomical language may seem far removed from patient experiences, gendered terminology is already creating challenges in healthcare settings.

A recent policy change in both Australia and the UK suggesting more gender-inclusive language for birth workers created some confusion about how this terminology should be applied in actual healthcare settings.

Policy changes like these, however, are important. For trans and gender-diverse individuals, healthcare experiences and outcomes depend on a healthcare providers’ comfort with, and respect for, gender diversity.

Misgendering – or using the incorrect gender – is not only frequent, but also contributes to the stigma faced by trans and gender-diverse individuals, with flow-on effects on their mental health and wellbeing.

Hence, the language we use when referring to patients and their bodies can contribute to the systemic inequalities they find when accessing healthcare.

Finding a healthcare environment that is safe and validates their gender identity makes a huge difference on the care provided. Without it, we risk an increase in the likelihood of healthcare discrimination and injustice.

Where do we go from here?

Education and awareness about alternative language and the inappropriate conflation of sex and gender is an effective first step.

At Monash, we’ve started integrating safe-space discussions where staff can discuss, share ideas, and ask questions about the “how” and “why” of decoupling gender from sex.

For those teaching anatomy, or using anatomical terms to communicate within the healthcare field, removing gender from references to structure is another valuable action.

Instead of stating “the female patient/donor”, a simple alternative could be “this patient/donor with a uterus”.

When writing questions or cases, we’ve started including “self-identified gender”, where a patient might be required to disclose their gender (for example, on an intake form).

Read more: Shrill, bossy, emotional: Why language matters in the gender debate

Similarly, other useful terms, such as “assigned female/male at birth”, can be used as clinical shorthand to convey anatomy typically associated with male or female – for example, when discussing fertility or sexual health. This can help set the foundation for gender-inclusive care further down the track. A recent article from the UK provides additional practical steps for inclusive curriculum development.

In clinical settings, inclusive language is achievable. All it takes is patient-centred care and communication, both of which are tenets for improved healthcare outcomes across all patient populations.

When working with trans and gender-diverse patients, it’s important to ask whether there are specific terms they would like to use for their body. Some people might find the gendered association with the term “breast” distressing, and prefer the term “chest”.

Similarly, asking whether there’s any specific terms people use for their reproductive anatomy is an easy way to avoid misgendering and miscommunication.

While most people who go through the medical system are perfectly happy using the standard medical terms, adopting gender-affirming care in clinical practice can make some much-needed space for trans and gender-diverse individuals.

Beware the one-size-fits-all approach

It’s important to recognise that a one-size-fits-all anatomy language won’t work. Knowing which terms to use when, and for whom, is key to inclusivity in healthcare.

For example, referring to a cisgender woman as “assigned female at birth” may result in an unnecessarily cold and clinical patient visit.

Read more: Gendered language and its role in fostering prejudice

Ultimately, having a gender-inclusive language expands our ability to communicate with every body, and better represents the science underpinning sex and anatomy.

By engaging a more inclusive language that better represents the spectrum of anatomical structures represented, we create a space safe for all genders, which in turn improves healthcare outcomes.

As the language continues to evolve, the gaps in communication will improve, and gender bias will continue to be diminished.

This article was co-authored with Dr Asiel Adan Sanchez, a non-binary doctor, writer and advocate who works in general practice, with a special interest in HIV medicine, sexual health and gender-affirming care.