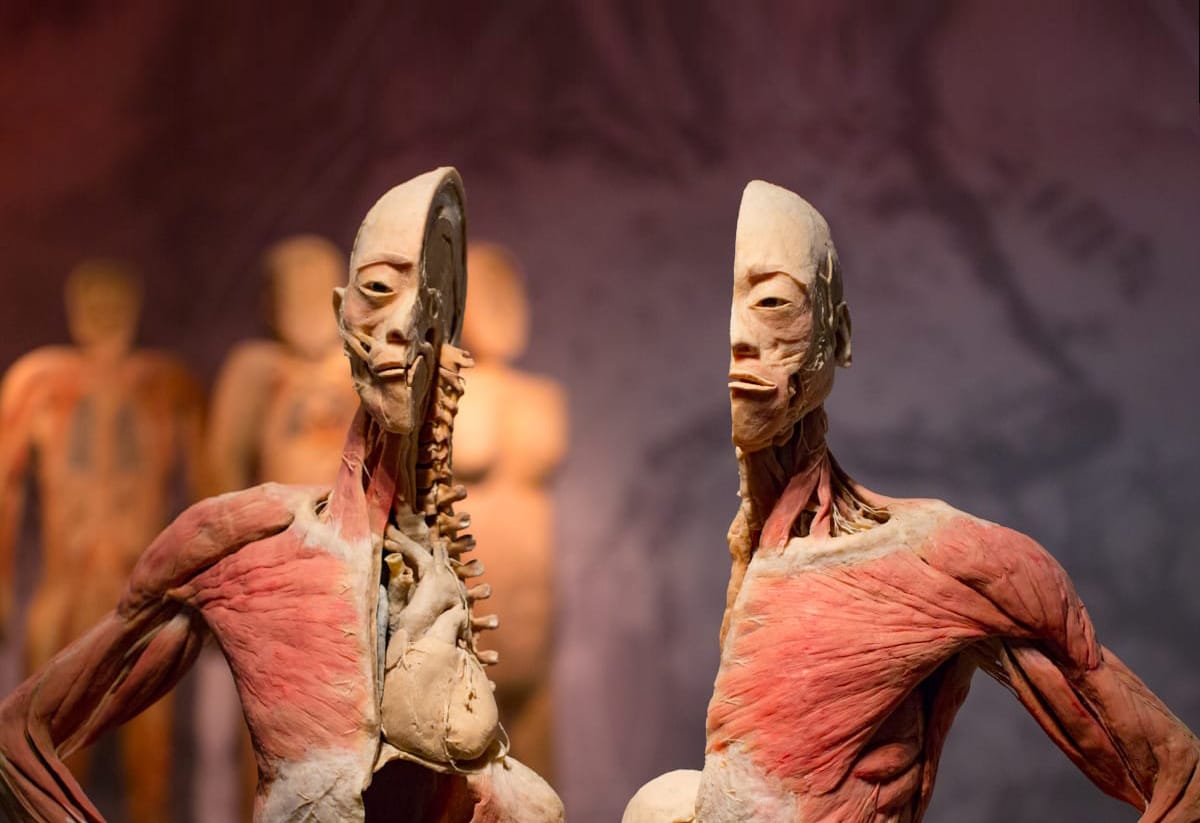

Protesters are urging a boycott of Real Bodies: The Exhibition, which recently opened in Sydney, due to the possibility that the plastinated human bodies and organs on display were taken without consent from executed Chinese political prisoners.

The chief executive of the company behind Real Bodies, Tom Zaller, has defended the exhibition. He claims that although the bodies come from China, they were legally sourced from people who died from natural causes and were unclaimed. The exhibition also cleared Australian bio-security checks.

The New South Wales Department of Health states that bodies or human tissues sourced from international institutions must meet its ethical and legal standards, which includes donor consent forms to be publicly displayed. Zaller admitted that there is no proof of the bodies’ identities or donor consent forms, raising questions about whether NSW regulations have been met. A group of lawyers, academics, and human rights campaigners, from the International Coalition to End Organ Transplant Abuse in China, has called for the exhibition to be shut down in an open letter.

This is not the first public anatomy exhibition to face claims of unethical body sourcing.

German anatomist Gunther von Hagens, who invented the plastination technique, has toured his controversial yet popular Body Worlds for two decades. In 2004, he returned seven corpses to China after conceding they may have come from political prisoners. There are also accusations that von Hagens sourced corpses for display from the mentally ill and homeless in Russia, which von Hagens denies.

We don’t know whether or not the bodies in Real Bodies were unethically obtained. But, we can look to the past to see how attitudes towards the collection and display of human remains have changed in recent decades. We can also consider how Australian museums negotiate these issues today.

Australian states and territories have their own regulations for the collection of human remains. Some also include directives for their display. It is then up to museums to develop policies for publicly displaying human remains. In short, museums should provide statements about the provenance of displayed bodies to avoid misleading the public.

Chequered history

Australia has a chequered history of collecting and displaying human remains. In the 19th century, Australian universities began to collect specimens of human anatomy and pathology. These formed an important part of medical education. However doctors and anatomists often took body parts from corpses without consent from the family or previously obtained from the person, and flouted regulation and convention to add interesting specimens to university collections.

In 1903, South Australia’s Inspector of Anatomy, Dr William Ramsay Smith, was accused of keeping parts of bodies that should have been buried in a proper coffin within church grounds. Prominent Sydney anatomist J.T. Wilson had also faced scrutiny a few years earlier for unlawfully removing a man’s skeleton from a hospital post-mortem room.

University collections were not open to the public. They were only for medical students and researchers to learn about the human body and the diseases that affect it. Although several protests took place in the 19th century about the practice, Australian medical schools continued to collect human remains throughout the 20th century for educational purposes, but now with some of these ethical considerations in mind.

There is also precedent for public debate over anatomy collections for public entertainment and amusement. In 1869, a letter to The Age accused the owners of a public anatomical museum in Melbourne’s Bourke Street of “groping the gutters for a livelihood”. Similar criticisms are being levelled at Real Bodies - even though it may also have the power to educate the public.

Ethical concerns about collected human remains grew in the 1980s and 1990s. In response, Australian museums began to develop policies and practices for their display. Museums took a cautious approach, particularly for the collection and display of Indigenous Australian human remains. Such remains had been stolen from graves throughout the 19th and 20th centuries for scientific and racial studies. This remains a source of immense distress for many Indigenous Australians today.

Australian universities began talks in the 1980s about the future of their collections. These discussions juggled the ongoing importance of anatomy museums in medical education with historical issues of consent. The National Museum of Australia ceased to collect Indigenous Australian remains in the mid-1990s. In 2009, it decided to stop seeking human remains altogether. There are also increasing moves to repatriate Indigenous remains. Although some museums have not supported this, pressure is building for them to support the requests of Indigenous communities for remains to be returned.

Recently, Museums Victoria decided not to display human remains from the Vikings: Beyond the Legend exhibition to avoid possible distress to Indigenous Australian visitors, after consulting with Indigenous communities. Remains, the museum stated, could cause “distress and sadness” due to “past practices of museums who displayed Ancestors without permission” and the spiritual belief that Ancestors should be laid to rest rather than displayed. Human remains featured in the Vikings exhibition at other global destinations.

Museums should heed the lessons of past grievances. This will ensure that future displays are in tune with cultural sensitivities and avoid getting into possibly murky ethical territory.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.