Cosmetic genital procedures are becoming increasingly popular in women. The most common is labiaplasty, which involves the surgical reduction of the inner lips of the vulva — the labia minora.

Most women who undergo labiaplasty in Australia do so through the private sector, which doesn't require reporting of statistics. But in the United States, procedure numbers have increased 30% in the past five years alone.

Of the labiaplasty procedures performed in 2018 in the US, 4% were on girls aged under 18. At this age, genital development is not yet complete, and there's significant risk of harm such as scarring, loss of sensation, and painful sexual intercourse.

We showed teenage girls an educational video on genital self-image. After the video, girls felt better about their genital appearance, and could more accurately name anatomical structures than before.

Genital concerns start early

To have a chance of making a positive impact on how adult women feel about their genital appearance, we have to reach them as adolescents.

Like appearance concerns focused on other parts of the body, our research suggests genital appearance concerns in girls start at a young age, particularly around 13. Most women undergo cosmetic genital surgeries in their 20s and 30s, as they have the finances to do so by this age, but they've often struggled with their concerns for a number of years.

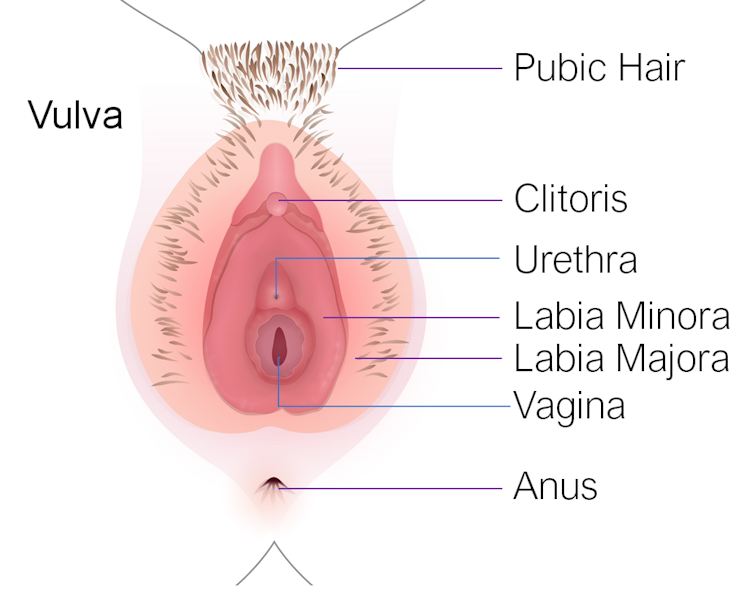

During puberty, the labia minora become more prominent after having been more hidden behind the labia majora (the outer genital lips) in childhood. One side of the labia minora may grow faster than the other, producing an “uneven” appearance.

Read more: Women don't always get what they want from labiaplasty

Labia minora are typically airbrushed out of sexualised media images, so girls may think their protruding or uneven labia minora are unsightly. This is particularly the case if they remove their pubic hair, which many teenage girls do.

This is also a time when girls may think about becoming sexually active, which means they may be showing their genitals to a sexual partner for the first time. If this sexual partner has a negative reaction to their genitals, it can lead to genital concerns and pursuing surgery.

How to educate teenage girls about their genitals

To educate teenage girls on such a sensitive topic as genital self-image, we designed a two-minute animated video. The video was age-appropriate, as it did not include any explicit images. It discussed genital anatomical features and their function, as well as the diversity of genital appearance, and challenged the airbrushed “ideal” for genital appearance.

The video also showed examples of the different types of genitalia through artistic representations and medical illustrations.

Our study involved 343 girls, aged 16-18, living in Australia, via social media. It was published recently in the journal Body Image.

We conducted the study through an online survey. All girls completed short questionnaires about how satisfied they were with their genital appearance, how likely they were to undergo labiaplasty in the future, as well as their ability to match up genital anatomy terms (such as vulva, clitoris and labia minora) with the correct anatomical structure on a diagram.

We then showed half the girls our video, and the other half a control video. The girls then completed the same questionnaires on genital appearance satisfaction, consideration of labiaplasty and genital anatomy knowledge, so we could compare their pre- and post-video answers.

What we found

The video improved girls’ genital anatomy knowledge from around 75% to almost 100% correct on average.

Compared to previous research in adult women, the teenage girls were considerably more concerned about their genital appearance and likely to undergo labiaplasty prior to watching the video.

However, the girls were about 7% more satisfied with their genital appearance and 8% less likely to undergo labiaplasty in the future after watching the video. These improvements were on the smaller side, but impressive given the video was only two minutes long.

We also asked girls for recommendations for teaching other young people about genital self-image. Along with the common recommendation to show our video, the girls talked about reaching people at a young age, and teaching it to all genders.

One girl told us:

"Get in as early as possible. Girls begin to worry and be confused about the changes in their bodies long before sex education is usually taught at schools. It would also help to normalise talking about female genitalia at a younger age, because there is such a shame and stigma attached to it."

Another girl said:

"Showing young people images of all types of female genitals to show them that what is seen in popular culture and in particular porn is not how all female genitals look. Explaining to females that they should not be concerned with their genital appearance, and educating boys and girls not to comment on women’s genitals."

We need to start talking with people as young as possible in an accurate way, including information about the diversity in genital appearances.

Part of this discussion involves the need to challenge the messages young people are receiving in wider media by improving their critical media-engagement skills. This has the capacity to change people’s perspectives about what bodies are considered normal and desirable, increasing their body confidence and sexual self-esteem.

Gemma Sharp receives funding from an NHMRC Early Career Research Fellowship. She's working in collaboration as part of the Active* Consent program, to develop an online sexual media literacy intervention that challenges genital appearance norms, and aims to increase body confidence among adolescents of all genders.

The article was co-authored with Kate Dawson, postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Ireland, Galway. Kate is a team member of the Active* Consent program.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.