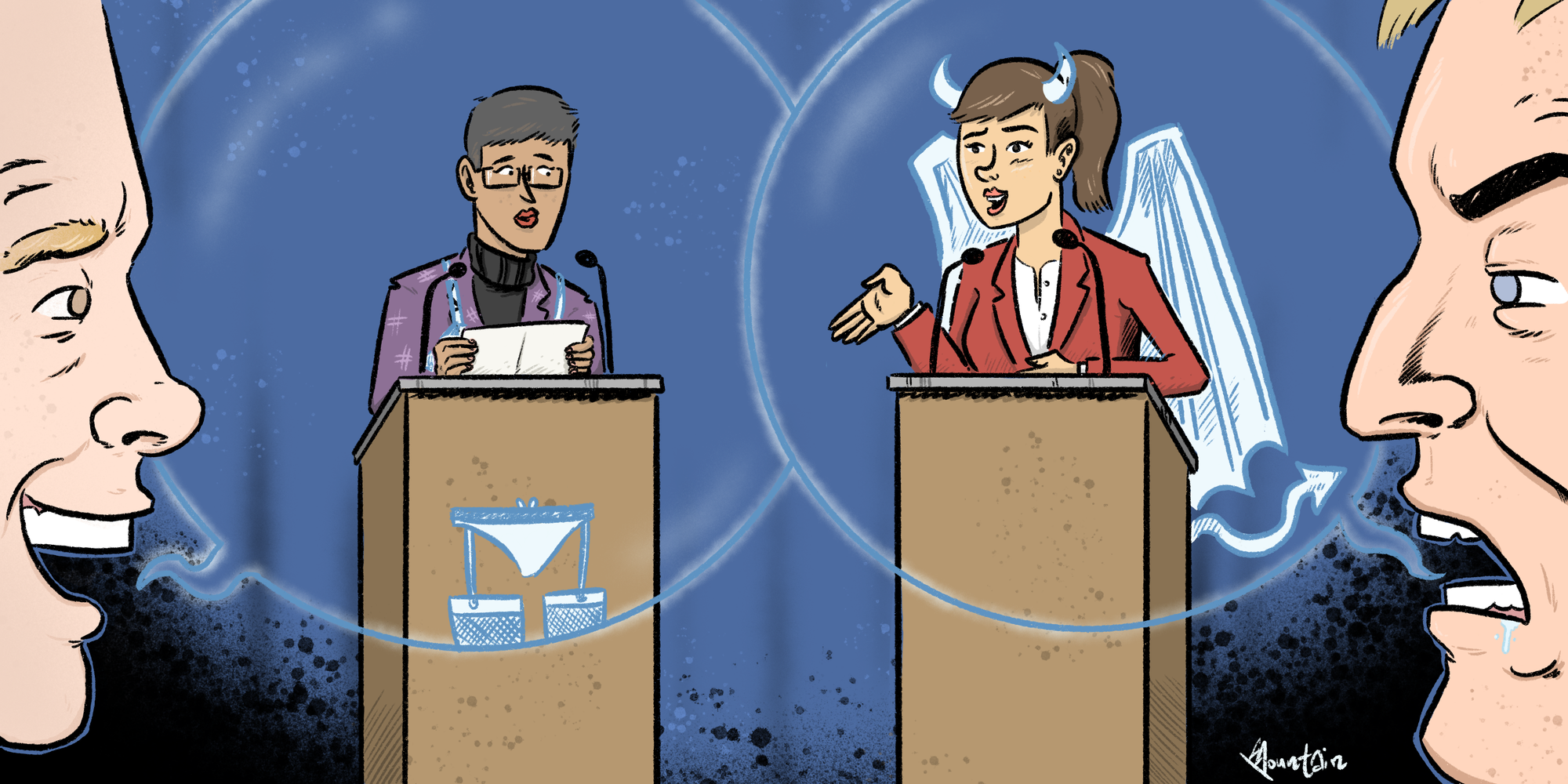

There's been much debate recently about the way women who work in our federal parliament are treated. This discussion has highlighted that society continues to place very different values on the way women and men behave.

Language – as a behaviour – holds a mirror up to these values. And changing the way we think about language is an important step towards changing the way we think about gender.

Read more: From 'arse-ropes' to 'flying venom': A history of how we’ve come to talk about viruses and medicine

Smoke-and-mirror fixes for folksy sneer winces

Folk wisdom provides a dizzying array of misleading accounts of how women communicate, many of them riddled with sexism. Proverbs tell us “women’s tongues are like lambs’ tails; they are never still”. But research tells us men talk and interrupt more – especially when they’re speaking to women.

It’s hard to stop the proverb and folk juggernaut once it gets started. It’s much easier to tell tales. And these are tales of linguistic problems, particularly for women in the workplace. Descriptions such as “shrill”, “hysterical”, “scold”, “emotional” – the list goes on – speak to the wider truth that women’s language is policed more aggressively and condemned more readily than men’s.

British TV producer Gordon Reece reputedly mused “the selling of [former UK prime minister] Margaret Thatcher had been put back two years” with the broadcasting of Question Time, as “she had to be at her shrillest to be heard over the din”.

More recently, Donald Trump said Hillary Clinton’s raised voice made her sound “shrill” and “too much”. And, of course, closer to home, Tony Abbott called Prime Minister Julia Gillard “shrill and aggressive”. Gillard suffered an onslaught of criticism for her accent and non-standard English, whereas Bob Hawke was celebrated for his.

Australian linguist Lauren Gawne also pointed to other features condemned in Gillard’s language, including sentence-final prepositions, passive voice and over-abundant adverbs. These are all features widely used by other politicians, and indeed by English speakers generally.

Sadly, the response to linguistic judgments seems to be a desire to “fix” women’s language. All kinds of advice literature instruct on how to replace these undesirable ways of speaking and writing with better ones.

Thatcher is probably the best-known example of someone who underwent a complete linguistic makeover. She famously altered her accent and her delivery, and deepened her voice by nearly half the average difference in pitch between male and female voices.

In 2015, a Gmail plug-in (Just Not Sorry) was developed largely with women in mind. Like a grammar or spell-checker, it highlighted for correction such features as hedging expressions such as just, I think and sorry. The development of the Just Not Sorry plug-in was well-intentioned – it emerged from a networking event at which women worried words like these made them look like pushovers.

But quick fixes like the Just Not Sorry plug-in don’t engage with the broader issue that society shouldn’t be policing women’s language. Moreover, it doesn’t stop to consider that so-called women’s conversational styles – found in many studies to be more cooperative, polite and collaborative – might lead to better outcomes in the workplace.

Baronet, King Kong and the dame in the creek: What words tell us about society

“Shrill” hints at an English lexicon that doesn’t reflect kindly on women. A lexicon is not an inanimate beast, but rather a social one. The social beast shines through in this Australian schoolyard chant:

Boys are strong,

like King Kong,

Girls are weak,

chuck ’em in the creek.

And the Oxford English Dictionary entry for “sex” highlights the corresponding linguistic imbalance. Here women are referred to as the “weaker”, “fairer”, “gentler” and “softer” sex, while men are the “stronger”, “sterner”, “rougher” and “better sex”. However, we might mention on an optimistic note that the adjectives associated with men are now listed as “rare”.

Synonym dictionaries like thesauruses are also revealing. The entry under “woman” shows an abundance of expressions for a sexually active or available woman. Many are appallingly derogatory.

The comparable set under “man” is considerably smaller and noticeably less negative. Labels such as “rake” or “womaniser” have nothing of the same pejorative sense of sexual promiscuity – there’s nothing equivalent to “whore” or “slut”.

What has given rise to this imbalance is the fact that words referring to women are unstable and typically deteriorate with time. Words such as “lady” or “dame” show the mildest form of deterioration. These referred to persons in high places, but then became generalised – compare the stability of the once-comparable “lord” and “baronet”, and others such as “governor”, “master”, “sir” versus “governess”, “mistress”, “madam”.

Even more striking is the way words meaning simply “young woman” take on negative connotations. Some expressions even start off referring to males, but once they narrow to female application they’re quick to take on overtones of sexual immorality. This is true not just of old expressions such as “whore”, “slut” and “slag” – in the case of Modern English’s “bimbo” and “skank”, the changes were extremely rapid.

Sissy pricks and twatty prats: Insults and gender

While we’re on the subject of asymmetries, we might also point out the vast difference in wounding capacity between insults invoking male and female sex organs. The most striking is “cunt”, meaning “nasty, malicious, despicable”, versus “prick”, meaning “stupid, contemptible, annoying”.

Moreover, while “cunt” (and its gentler counterparts “twat” and “prat”) freely apply to both males and females, females are rarely, if ever, abused by “prick” and “dick”.

Should women be concerned by this, you’re probably wondering? Only in that it’s indicative of a more general story. Terms for women are insulting when used of men (for example, “throws like a girl”, “old woman”, “sissy”), but there’s no real abuse if male-associated words are used of women. In fact, “she’s ballsy” was said of Thatcher in praise of her strength of character.

Language is a mirror and a lens

Our language behaviour – perhaps best illustrated by the lexicon – provides particularly clear windows into speech communities. If you’re not convinced already, consider the staggering 2000 expressions for “wanton woman” that English has amassed over the years. This says it all really – a linguistic tell-tale of sexual double standards. Even the adjective “wanton” no longer refers to men.

These asymmetries in our language are significant, and we haven’t even started on the maledictions invoking animal terms! Language both reflects and reinforces the thoughts, attitudes and culture of the people who use it, and that’s why language matters when it comes to talking about gender.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.