“I do a terrible job talking about myself,” says Monash University’s Dr Harry Al-Wassiti, as he sits down with Lens to tell his remarkable story. “But I’ll try.”

The tale begins with a boy in war-torn Iraq at exactly the wrong moment in history, and ends – although the story’s far from over – in Melbourne, deep into COVID-19 lockdown, with Dr Harry joining the global chase for an elusive vaccine to the virus.

To say he’s come a long way is to grossly understate his journey. He and his family nearly didn’t make it this far.

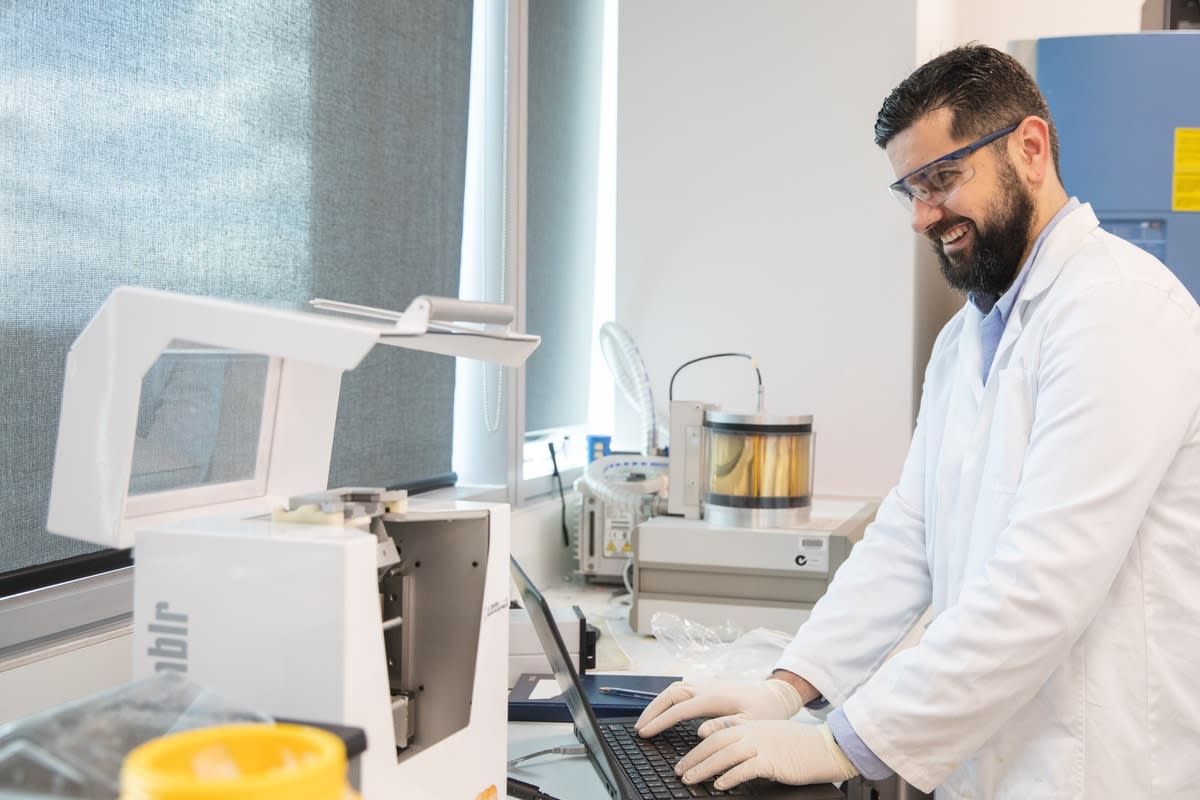

Today, Harry is part of a team from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Parkville using new technology – similar to DNA, but also slightly different – to try to make the vaccine, and make it quickly.

The chase for this elusive vaccine is itself a kind of warfare, although using a military metaphor after what Harry’s been through in real life might not be totally appropriate. But there is an enemy that’s clever and fast, and strong. The only way to rid ourselves of it, and prevent its reappearance, is to strengthen the defences.

It’s a fight for the lives of, potentially, millions of strangers.

The beginnings in Baghdad

But first Baghdad, 2003. Harry is still Hareth – he’s 15, and a high-school student from a secular middle-class family in the suburbs of the city. His father owns a factory making electrical switchboards. He has an older brother and sister. His mother and father came from different branches of Islam – Sunni and Shia – but the family don’t align themselves strongly with either.

It’s the wrong time in history because, following the 9/11 terror attacks two years previously, the second Gulf War begins, focused on Iraq. The New York towers were destroyed by Al-Qaeda, a Muslim extremist group with links to Iraq, a country run by a dictator, Saddam Hussein, since 1979.

During his reign, he took Iraq into war with neighbouring Iran, using chemical weapons against Iranian civilians. He also ordered the genocide of Iraqi Kurds and some Iraqi Muslims. He also invaded Kuwait, beginning the first Gulf War. When he was ordered to get rid of his biological and chemical weapons, he refused. So when the Twin Towers came down, the United States and allies invaded Iraq in what was dubbed the “War on Terror”.

None of this was anything to do with young Hareth. He and his family thought an invasion and war would clean out the old, corrupt Iraq, and usher in a new era. But all hell broke loose. The Americans and their allies were fighting the Iraqis, and the Iraqis were fighting among themselves.

As a secular family who believe government is separate to church – and not attaching themselves with sectarian branches of Islam, or Christianity – the Al-Wassiti family were vulnerable and exposed.

By early 2003, Harry’s home town of Baghdad, the capital city, was being destroyed around him, by all sides of the conflict, and the city was a highly dangerous, unpredictable war zone.

In just a month, the city was basically taken over by the Allies – with open shooting, bombing, and looting in the streets – and Saddam’s statue was famously toppled. About 7000 civilians had been killed.

“I lost a couple of friends who got assassinated – they were killed in the street. There were kidnappings of people I knew. A lot of young men disappeared and didn’t come back."

The aftermath of the war, with continued fighting and insurgents spilling in from Syria, with Baghdad torn asunder, was “chaos”, says Harry.

That’s when his friends started being killed or disappearing. He was 17 by now; it was 2005.

“It was a frightening time,” Harry says. “I lost a couple of friends who got assassinated – they were killed in the street. There were kidnappings of people I knew. A lot of young men disappeared and didn’t come back. You had two options as a young man – join a religious group, or they will come at you.”

One friend the same age as Harry – they went to primary school together and lived in the same neighbourhood – was shot in the street. It was a defining moment in Harry’s life.

“What they did to him was really quite graphic. It was a terrible thing. There’s a lot of stories like this. I was devastated. Angry. They shot him. He was Christian, and they were targeting Christians. But for us, the scale of this was almost normal.”

Then came the letter, and the bullet.

“I remember it very vividly,” he says. “We were getting threats. We were not unique in that – there was a week where a few houses in the same street as we lived in got threats. There was a letter under our fence saying, ‘You have to leave this area’, and there was a bullet in the letter.

“My dad was like, ‘We can’t stay here’.”

Harry was in his first year of university – studying pharmaceutical sciences – in Baghdad. He felt a sense of loss, because with the war had come that hope. Now it looked hopeless.

“I was angry. ‘What I have lost?’ We were hoping for a better future. We were hopeful that things would work out better – until we got the threats. When I was at university in Baghdad I had good friends, I was building relationships, I liked a girl, all these things of first-year university. But it became a dark period, a lot of people getting picked up. We decided we had to go. I was very angry, but I didn’t resist it, because I knew it was right to leave because I was probably one of the prime targets. Young men were the first they went for.”

A new start in Jordan

The family fled to neighbouring Jordan, except for Harry’s courageous father, who stayed in Iraq for another year, hiding out at his own mother’s place and organising family affairs for their new life, whatever and wherever that would be.

Harry started at Applied Science University in Amman, the capital of Jordan, to continue his pharmacy studies – and finished them there, because the family stayed for four years. His sister and her husband, meanwhile, had started applying for visas to come to Australia. “My father said, ‘Let’s go! Let’s go the furthest away we can.’”

Eventually, the visas were approved and the family moved – Harry’s sister first – to Dandenong, in Melbourne. When Harry arrived it was mid-winter, and cold. This was when Hareth became Harry. He remembers the date – 1 August, 2010.

“It took me a while to adjust. There was cultural shock. It was cold, raining. Crazy, really. I thought it was going to be kangaroos and sunshine and beaches. Where are the beaches?”

His brother and wife settled across town, in Brunswick, but the rest of the family were in Dandenong. After two weeks in Melbourne they went driving to the Mornington Peninsula and saw the beaches, but most of all it was about trying to adjust, in their own ways.

Harry’s friend Martina Sanchez, who he would soon meet in a public library, describes him as determined and grateful. “He was not mucking about,” she says. “He knew he had been given a second chance, and he was certain about using it.”

He was a long way from the Middle East, but found a welcoming Middle Eastern community in the bustling southeastern suburb. He got a job in a Turkish halal butcher, “chopping up chickens, cutting up meat”.

That’s because, even though he was a qualified pharmacist, he needed Australian accreditation to practise, which takes time. He was also behind the play – in his mind – with his English. He could read it, because he did all his exams back home in English, but he couldn’t speak it.

“I was like, ‘Wow’,” he says. “What am I going to do now? I had to find, I guess, a dramatic way to accelerate that, and to be very proficient in English. The way I did that was to completely mix myself with English-speaking people to be forced to learn it really well.”

“I have great admiration for the way Harry has had the courage and tenacity to keep strong, and keep working against the odds to develop his career and personal life in Melbourne.” – Professor Colin Pouton

Between shifts at the butcher, he would go to the Dandenong library, and that’s where he met Martina, a Chilean librarian. “She is a really sweet person,” he says. “We became friends, and she introduced me to her friends.”

She says she had started to see him regularly in the quiet area, reading. She says she thinks the library, as well as books, gave him a sense of certainty, or normality. It’s his “resilience” that impressed her most; the strength to start again. He picked up speaking English very quickly.

“Straight away, I could tell he would,” Martina says. She soon found out he was interested in science, and was, in fact, a scientist whose “world revolved around science”. One day she drove him to the Monash University Clayton campus and introduced him to the Sir Louis Matheson Library. She also took him on holiday to Venus Bay in Gippsland with her friends. His English became proficient.

The path to research science

Harry landed a job as an assistant in a chemist shop, once he got the right paperwork. Then it became all about securing his proper Australian visa so he could get a student loan and enrol at Monash to further study pharmacy.

“I was always very curious about the sciences,” he says. “I always liked solving puzzles and problems, inventing things, right back from my Lego days when I was a kid.

“I decided I wanted to be a research pharmacist.”

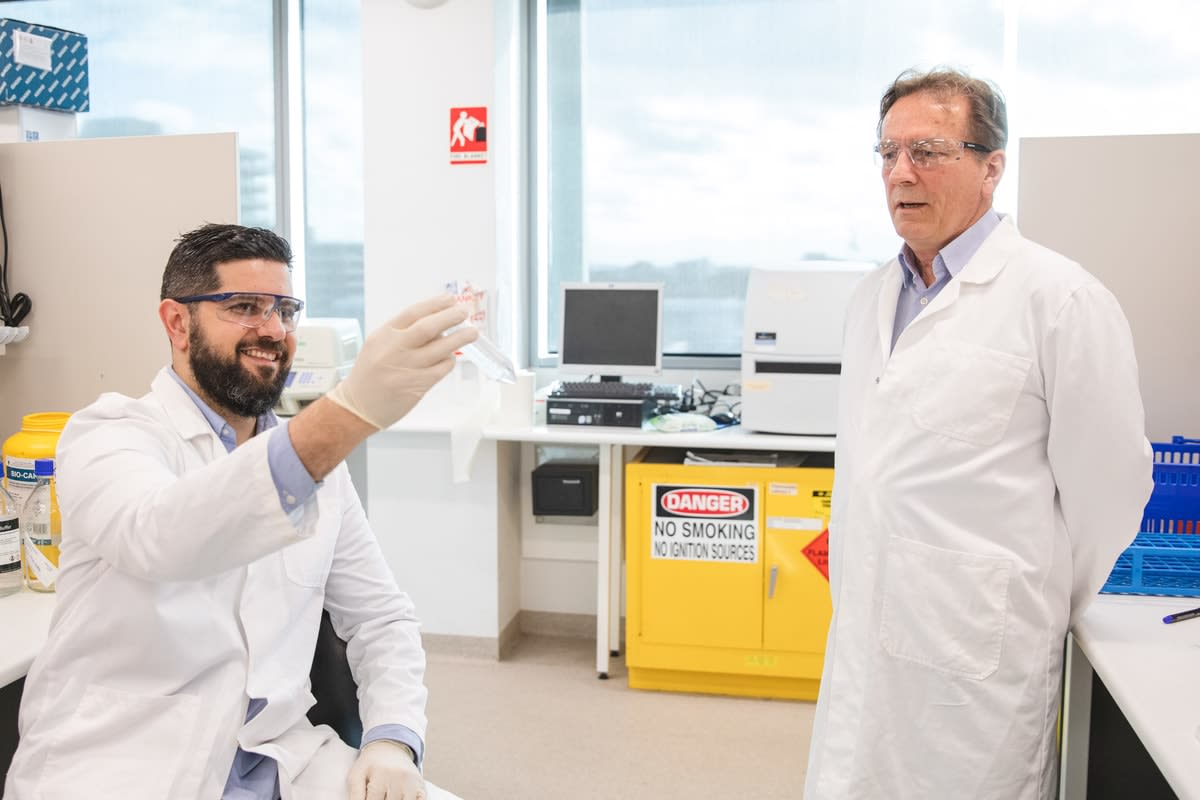

He did his honours at Monash, then his PhD. He branched into neuroscience, but then came back to research pharmacy, specialising in genetics. Now he’s part of Professor Colin Pouton’s lab in Parkville, on the hunt for the COVID-19 vaccine through genetic therapies.

Professor Pouton says Harry is a fine scientist. “He’s willing to take on a challenge and find his way around problems, by carefully reading papers and studying scientific techniques.”

As a person, Professor Pouton says, he’s a “very likeable, friendly, cheerful and cooperative person. He’s very appreciative of the help and advice he gets from people, and very respectful of their time. At the same time, he’s very determined to develop his career, and is keen on self-development.

“I have great admiration for the way Harry has had the courage and tenacity to keep strong, and keep working against the odds to develop his career and personal life in Melbourne.”

Harry explains his complex branch of science – and potential COVID-19 vaccine development – in simple terms. DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid) make everything in our cells, so “we use them, specifically RNA, therapeutically, by programming a cell to make a protein of interest”.

“If you’re missing a protein or have mutated proteins – like in, say, sickle cell anaemia – we give the RNA that makes the correct form of protein that will recover it. We replace the faulty gene in the cell.

“The question now,” he says, “with this pandemic, is ‘Can I program it to make a viral protein called an antigen?’ Then we can jump into the field of vaccination. We train the immune system to produce the viral protein to raise an immune response to tell the rest of the immune system about it. The body will now be well-prepared to fight a virus if it sees one again.”

Read more: Explained: The challenges of developing a COVID-19 vaccine

The researchers have produced what are known as “mRNA COVID-19 vaccine candidates” – the first in Australia. A similar approach has been used to develop the leading COVID-19 vaccine already being tested on people in the United States.

For Harry, the pressure this time comes from what he calls the “hype and hope” of a potential vaccine for the pandemic that has shuttered large parts of the world.

It isn’t war, with boyhood friends vanishing or dying in the streets, and it isn’t an exodus to safety with his loved ones. But, still, he says, it’s a fair weight on his shoulders. “It’s a difficult thing. We’re trying to develop a vaccine for something we have never faced before. People are dying. It’s a huge challenge, and a big responsibility.”