When it comes to selling bottled drinks, size matters. Or, more precisely, width.

“Some bottles are just too wide for the Chinese palm,” says Dr Angeline Achariya, revealing unexpected, and human, realities that food and beverage manufacturers meet when entering new markets, in this case, China.

Dr Achariya is CEO of Monash University’s Food Innovation Centre (FIC), which provides its clients with this type of product and consumer intelligence as they aim for a foothold into food markets around the world, particularly the burgeoning economies of Asia.

Through its range of research-based services and connections with international retailers and distributors, including the A$100 billion Chinese food company COFCO Corporation, the FIC aims to help food producers ‘de-risk’ their innovations to increase their chances of succeeding.

And to step beyond the conceptual, ‘ideas are brought to life’ by FIC designers using 3D printers so clients can see and feel their product – and the real difference that size and shape, for example, can make.

“It’s tangible,” says Professor Nicolas Georges, director of the Food and Agriculture Initiative at Monash, in which the FIC plays a critical part.

“At some point you need to touch and feel the product – and that should be before it’s on the shelf and before you are wondering why it’s not selling.”

Bypassing expensive manufacturing and prototyping processes, 3D printing ensures producers can identify quickly and relatively cheaply what will work, and what won’t. “If we fail, we need to fail fast,” Dr Achariya says.

Failing fast and learning quickly at the incubation stage of product development is critical, she says, because globally, only one in 10 new products survives beyond a year. “So we help businesses go fast in new product innovation and design, but we also help reduce the risk of innovation by helping to prevent failure at key development points.”

Critical junctures

Beyond the shape and feel of a product, critical development points include the product’s packaging (glass or plastic) and the colour and design of its label as it vies for consumer attention on supermarket shelves.

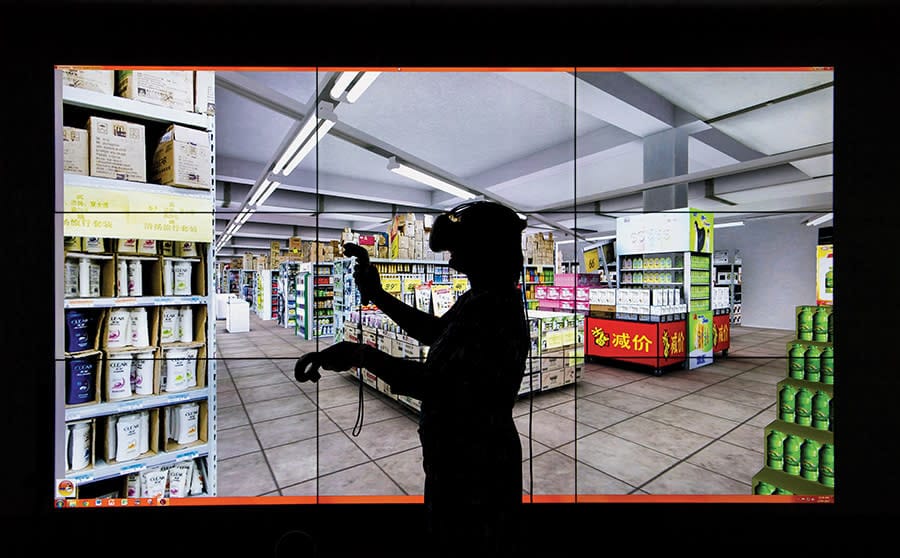

Insights are generated through virtual supermarkets developed with virtual reality partner 3DVR. Based on the floor plans of stores from around the world and beamed on floor-to-ceiling screens at the FIC and the University’s circular virtual reality space, CAVE2, the technology immerses clients into particular retail settings.

“When a product is dropped into a virtual supermarket ‘planogram’ [retail speak for the display of products] you can see what it looks like on the shelf, in the context of a real store, with very little cost or risk,” Dr Achariya says.

“Particularly in markets like Asia, shoppers eat with their eyes first – so you really need to make sure your design cuts through all the clutter,” she says.

Eye-tracking technology provides further insights into where consumers look, how long they linger over a particular product category (at six to nine seconds, people spend more time looking at chocolate or ice cream than other products) and therefore what design features a product needs to catch the consumer’s eye.

But underlying this technology, and often the first step, is ensuring the product has a place in the market. Using the FIC’s product-mapping tool, clients can see laid out before them where there might be gaps or ‘white space’ in a category – and this will help determine the type of product they develop, including its look and price-point.

All these tools work, along with the FIC’s consumer researchers, to identify what Professor Georges calls “human truths” – the factors that make us buy what we buy. They can range from the physical and practical, such as whether it fits comfortably in the hand, to values associated with particular colours or looks.

By identifying these truths, the FIC can help producers succeed by designing and positioning their product appropriately. And through this process, the aim, says Professor Georges, is to encourage further innovation. “We want them to be more ambitious, because we are helping diminish the risks.”

Bridging cultural divides

Established in 2013 to help food producers capitalise on the fast-growing demand from China for Australian-made goods, the FIC was first located on the Melbourne premises of multinational food company Mondelz, jointly funded by the Victorian state government.

When that tenure ended, Monash University’s Industry Partnerships director, Dr Joseph Lawrence, saw an opportunity for Monash to invest in a unique resource that would increase the University’s innovation capabilities in this crucial sector for Australia on the global stage, while providing industry with a depth of expertise, talent and infrastructure.

“It’s about achieving impact together and creating opportunities for the sector, and ultimately that translates to a better world and economic prosperity,” he says of the FIC partnership – one of many Monash funds through joint industry and government investments worth more than A$100 million.

And in the ‘global village’ of a university setting where the FIC has been housed since mid-2016, the collaborative opportunities are growing.

As part of the wider Food and Agriculture Initiative at Monash, the FIC functions as a bridge between primary research and industry development.

It’s a bridge that gives industry access to the best technology and research, and one that must span a fairly deep chasm: “For all universities the challenge of engaging industry remains both a priority and a conundrum,” says Professor Georges, who, as a past director of R&D at Mondelz, has experience in both camps. He says this is because industry is inherently risk-averse with a short-term, profit-driven outlook, while researchers are inherently are risk-takers with a longer-term view.

“Research is like the oil and industry the water,” Professor Georges says.

“We are the emulsifier helping them to mix.”

Food science plates-up the future

The FIC achieves this ‘emulsification’ firstly by attracting industry to its services, workshops and symposiums on such topics as 3D food and personalised nutrition. Then, with risks diminished and the mindset of industry more open to ideas, it is more likely to “take bigger bets” exploring further research opportunities for greater impact, Professor Georges says.

Identifying these opportunities was Professor Georges’ priority when establishing the Food and Agriculture Initiative and a range of associated research projects with commercial outcomes in 2016.

Harnessing the University’s strengths in medical research, pharmacy and engineering, he identified four platforms – or ‘translational clusters’ – under which joint projects partnered by industry and researchers from various disciplines would operate.

These clusters – Personalised Nutrition Foods, Food Integrity, Biomass Valorisation and Food Security – connect industry and researchers to address some of the most significant issues facing the food sector and society in light of an ageing and growing population, including the rising cost of health, food security and environmental sustainability.

“Because the world is changing, these forces will apply to our sector, and so whoever is capable of anticipating and providing offerings for those forces will be able to create value,” Professor Georges says.

A project team working under the Personalised Nutrition Foods cluster, for example, may bring together a nutritionist, medical researcher and chemist, along with an industry partner, to create food that helps prevent illness or addresses specific health complications such as sleep or digestive disorders.

The Food Integrity cluster might look at technology to keep food fresh and reduce waste to combat the 30 per cent of products that are never consumed. Also tackling the issue of food waste is the Biomass Valorisation cluster, which is looking at technology to transform biowaste into other foods or products, including energy. Meanwhile, the Food Security cluster examines supply issues such as water and soil management.

Such projects are led by a PhD student under the Graduate Research Industry Partnerships (GRIP) initiative, which brings doctoral students together with academic leaders and external partners to work on real-world issues. “We create these teams for industry and the researchers to co-create a solution they will commercialise,” Professor Georges says.

One-stop science hub

Monash has the expertise to deal with overarching issues such as nutrition, waste and sustainability, and also has the infrastructure to support it. This enables translation very quickly, Professor Georges says.

“When you talk about Personalised Nutrition, for example, two minutes one way there is a clinic that can do sleep studies or sports testing; five minutes another way is the Monash hospital that can do genetic testing and work with clinical in-patients; in another direction there’s the synchrotron; then there’s brain imaging. So the reality is, almost anything you need, you can access through this particular hub,” he says.This hub also involves Australia’s national research organisation, CSIRO, an FIC research partner along with other universities, as well as a corridor of small and medium-sized food enterprises that the centre is working with.

“So it’s potentially a continuum with research flowing in and out of the FIC,” he says.

This capacity has been recently extended through a newly opened Incubator – a laboratory of fully-equipped kitchen and processing facilities for start-ups and small businesses to develop products.

It’s from these entrepreneurs that ideas will emerge, which may in turn feed into further research opportunities for the University, says Professor Georges, who describes the entire Food and Agriculture Initiative as an incubator for innovation.

Case study: Market moves

Well-known US yoghurt manufacturer Chobani has recently used the Food Innovation Centre (FIC) mapping tool to expand its product range in Australia. After identifying gaps in the market, it developed a handheld breakfast yoghurt and has reaped a net revenue of more than A$10 million within three years. It has also created a successful new range of dips.

“You have to be very dynamic because the market is constantly changing, so you have to keep adapting; otherwise you’ll get left behind,” says Chobani Australia managing director Peter Meek.

The company is also among those that have taken part in the centre’s intrapreneur program, designed, says FIC CEO Dr Angeline Achariya, “to build entrepreneurs within organisations”. As a result, Chobani’s R&D, marketing, sales and operations personnel came up with more than 180 ideas, of which 20 are in an “immersion pipeline” for development over the next three years.

“By taking part in the intrapreneur program, our team has been empowered to take brave steps to make change that will influence the future of our business and further grow our innovative nature,” Mr Meek says.

“One of the added benefits was it helped to bring the commercial, operational and development teams closer together. Participants became more aligned on future strategy, as well as forming a stronger and more inclusive culture overall.”

Meals printed to order

Would you eat beef that looked like a flower? 3D food printing is making this possible.

Food Innovation Centre (FIC) CEO Dr Angeline Achariya says that, more than a gimmick, printing beef in 3D is a high-value way to use offcuts that would otherwise be wasted. And it’s been tested – and tasted. At a recent symposium held jointly by the FIC and Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA), beef was 3D-printed, cooked by chefs and eaten by delegates to demonstrate the concept.

And the verdict? “It lost a bit of its texture,” Dr Achariya says.

The texture, soft to the bite, is a result of the slurry created from the raw product to enable its passage through the printer nozzle. A potential turn-off for some, this soft texture nevertheless points to real possibilities for a future market in 3D-printed beef in applications such as nursing home menus.

Dr Achariya says 3D-printed beef could be an option for elderly people with dysphagia – difficulty swallowing – which otherwise requires them to eat infant food. With a 3D-printed steak, they could eat something that looks like adult food yet has a much softer texture, helping them maintain a sense of dignity. The same could apply to any number of foods, such as carrots. “A 3D-printed carrot will still look like a carrot and taste like a carrot but be much easier to swallow.”

These are early-stage ideas on the drawing board for companies and organisations such as MLA, exploring new technologies through FIC-hosted symposiums “to get the industry thinking about the future”, Dr Achariya says.