Until it was hunted to extinction, the thylacine – also known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf – was the world’s largest marsupial predator. However, our new research shows it was in fact only about half as large as previously thought. So perhaps it wasn’t such a big bad wolf after all.

Although the thylacine is widely known as an example of human-caused extinction, there's a lot we still don’t know about this fascinating animal. This even includes one of the most basic details – how much did the thylacine weigh?

An animal’s body mass is one of the most fundamental aspects of its biology. It affects nearly every facet – from biochemical and metabolic processes, reproduction, growth and development, through to where the animal can live, and how it moves.

For meat-eating predators, body mass also determines what the animal eats – or more specifically, how much it has to eat at each meal.

Catching and eating other animals is hard work, so a predator has to weigh the costs carefully against the benefits. Small predators have low hunting costs – moving around, hunting and killing small prey doesn’t cost much energy, so they can afford to nibble on small animals here and there. But for bigger predators, the stakes are higher.

Almost all, large predators – those weighing at least 21 kilograms – focus their efforts on prey at least half their own body size, getting more bang for the buck. In contrast, small predators below 14.5kg almost always catch prey much smaller than half their own size. Those in between typically take prey less than half their size, but sometimes switch to a larger meal if some easy prey is there for the taking – or if the predator is getting desperate.

The mismeasure of the thylacine

Few accurately recorded weights exist for thylacines – only four, in fact. This lack of information has made estimating their average size difficult. The most commonly used average body mass is 29.5kg, based on 19th-century newspaper accounts.

This suggests the thylacine would probably have taken relatively large prey such as wallabies, kangaroos and perhaps sheep. However, studies of thylacine skulls suggest they didn’t have strong enough skulls to capture and kill large prey, and that they would have hunted smaller animals instead.

This presented a problem – if the thylacine was as big as we thought, it shouldn’t be able to live solely on small prey. But what if we’ve had the weight wrong the whole time?

Read more: Why did the Tasmanian tiger go extinct?

Weighing an extinct animal

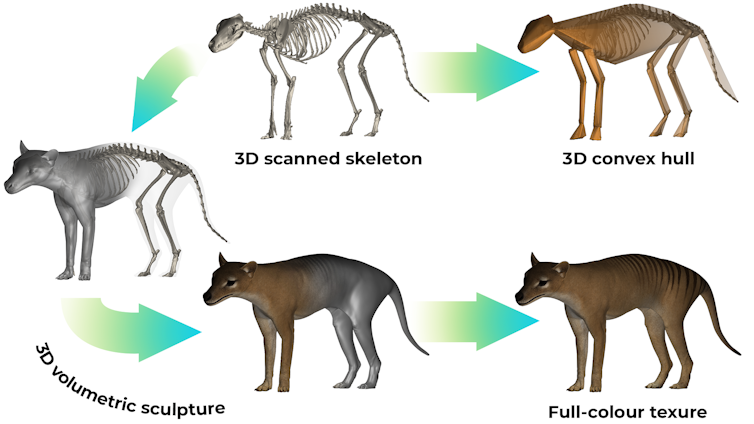

Our new research, published this week in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, addresses this weighty issue. Our team travelled throughout the world to museums in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe, and 3D-scanned 93 thylacines, including whole mounted skeletons, taxidermy mounts, and the only whole-body ethanol-preserved thylacine in the world, in Sweden.

Based on these scans, we created new equations to estimate a thylacine’s mass, based on how thick their limbs were – because their legs would have had to support their entire weight.

We also compared the results of these equations with a new method of digitally weighing 3D specimens. Based on a 3D scan of a mounted skeleton, we digitally “filled in the spaces” to estimate how much soft tissue would have been present, and then used our new formula to calculate how much this would weigh. Taxidermy mounts were easier, as there was no need to infer the amount of soft tissue. The most artistic member of our team digitally sculpted life-like thylacines around the scanned skeletons, and we weighed them, too.

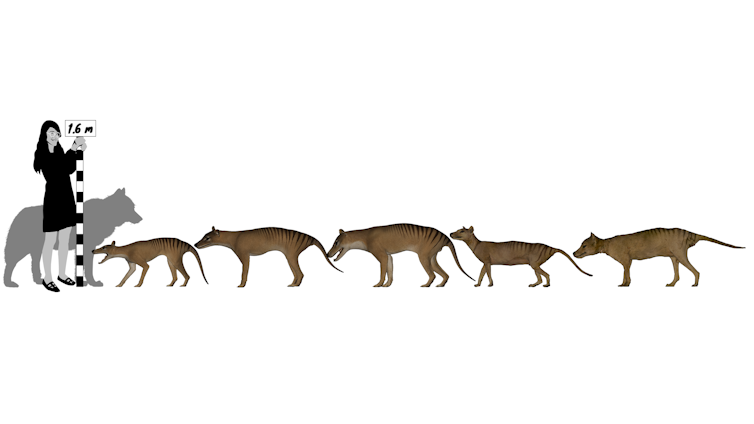

Our calculations unanimously told a very different story from the 19th-century periodicals, and from the commonly used estimate. The average thylacine weighed only about 16.7 kg – not 29.5 kg.

Read more: Friday essay: on the trail of the London thylacines

Tall tales on the tiger trail

This means the previous estimate, based on taking 19th-century periodicals at face value, was nearly 80% too large. Looking back at those old newspaper reports, many of them, in retrospect, have the hallmarks of “tall tales”, told to make a captured thylacine seem bigger, more impressive and more dangerous.

It was based on this suspected danger that the thylacine was hunted and trapped to extinction, with private bounties already placed on them by 1840, and government-sponsored extermination by the 1880s.

The thylacine was much smaller than previously thought, and this aligns with the smaller prey size suggested by the earlier studies. Predators below 21kg – in which we should now include the thylacine – all tend to hunt prey smaller than half their size. The “Tasmanian wolf” probably wasn’t such a danger to Tasmanian farmers’ sheep after all.

By rewriting this fundamental aspect of their biology, we're closer to understanding the role of the thylacine in the ecosystem – and to seeing exactly what was lost when we deliberately hunted it to extinction.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Douglass Rovinsky receives funding from the Robert Blackwood Partnership Monash-Museums Victoria Scholarship, and Monash University Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology.

Alistair Evans receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Monash University, and is an honorary research affiliate with Museums Victoria.

Justin W. Adams receives funding from Monash University.