Long before COVID-19 hit Sri Lanka’s shores, grassroots women’s organisations fought poverty pay, long hours, and unsafe working conditions in the country's garment manufacturing districts.

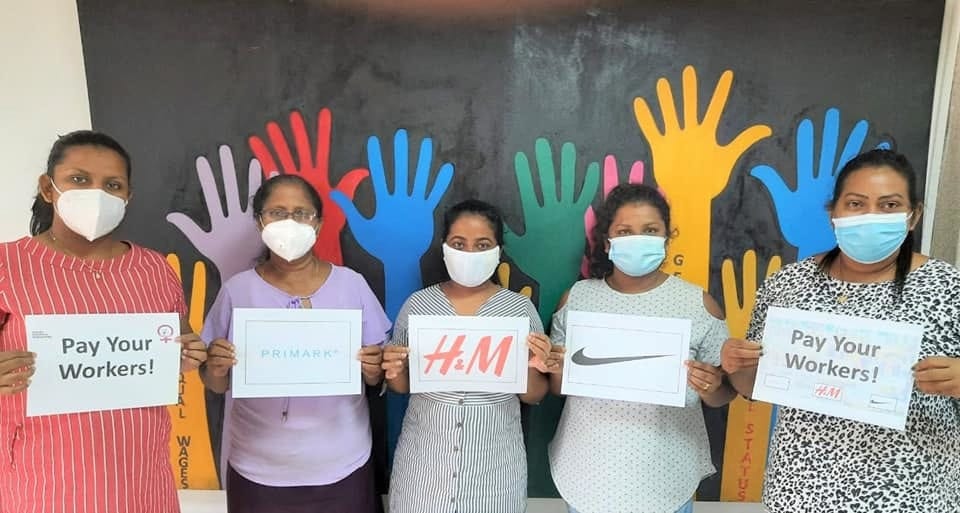

These organisations have been advocating for the people producing high-end clothing for brands such as H&M, Next, JC Penny, Benetton, Marks & Spencer, Gap, Victoria’s Secret, Ralph Lauren and Triumph.

Garments account for approximately 45% of Sri Lanka's export income. Up to 85% of workers employed in this sector are women working in assembly line operations, who earn between LKR12,000 and 20,000 per month (A$80 to $130).

Their labour has been crucial in maintaining the Sri Lankan economy through war (1983-2009) and post-war periods, as well as the economic shocks generated through disasters such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, or violence such as the Beeshanaya ("Time of terror") from 1987-91, and the Easter Sunday attacks (2019).

The COVID effect

After the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the country in late January 2020, the virus was at first contained. A militarised public health response, including an island-wide lockdown, was hailed as a success.

However, by early March, international garment orders had slowed. Then, on 27 March, instructions were issued by the Ministry of Industrial Export and Investment Promotion to close all free-trade zones until further notice. Garment workers did not receive wages. Many were stranded without transportation to their home villages, or had nowhere else to go.

By April, food insecurity became widely reported; many workers were also denied a government relief allowance of LKR5000 (A$33). Work resumed towards the end of April, but factories had started cutting their workforces, citing that international brands had cancelled or reduced their orders.

It was only in May that, after tripartite deliberation, a decision was taken to maintain labour conditions and wages. Politicians began to take limited action. However, employers were stepping up unethical labour practices.

The Women’s Centre in Sri Lanka has long used street theatre to communicate the experiences of women workers. In this dramatisation, they depict women workers' experiences and sorrow during lockdowns.

In October, a prominent garment manufacturing factory sparked a second COVID-19 wave. Reports emerged about inadequate personal protective equipment and hygiene processes within factories. Pay was cut, and workers (and their families, including young children) were subjected to severe treatment by the military when abruptly taken to quarantine centres. Working conditions continued to deteriorate for the rest of the year.

Leading from the front

While the work of high-profile and elite women is discussed widely, grassroots leaders’ work is less documented. Women’s community-based organisations have been on the frontline of various pandemic responses, from Ebola and Zika to COVID-19, but they're often excluded from crisis and disaster response planning.

Their work often remains invisible, although it's vital for sustaining the most vulnerable in their communities.

Overlooking the leadership roles women take on during a crisis can lead to gendered harm. The outcome is that diverse women’s and girls’ needs are neglected in policymaking, budget and resource allocations, and services provided.

As a result, poorly designed policy or misdirected resources insufficiently serves the communities they purport to help. This is true of mega-development projects, or peace processes, as it is of pandemic responses such as COVID-19.

The leadership of women activists and workers in Sri Lanka was vital in bringing attention to garment workers’ experiences, and getting redress for some of the injustices they faced during 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Working primarily in grassroots community-based organisations (as well as trade unions, although these tend to be male-led), women leaders and the other members of these organisations worked tirelessly to provide services, represent, document and advocate for women workers. They responded to garment workers in boarding houses around the Katunayake zone in the Western Province just outside the capital Colombo, and Matara in the Southern Province, Vavuyna in the Northern Province, and Trincomalee and Batticaloa in the Eastern Province.

As Ashila Nironshine from the Stand-Up Movement noted:

“We never stopped [our] work …” due to COVID.

Throughout 2020, I observed the Women’s Centre, Dabindu Collective, the Stand-up Movement, and Revolutionary Existence for Human Development (RED), which individually and collectively advocated for a free-trade zone and apparel sector workers. These organisations are all led by women, quoted in this article.

Faced with the lockdown that stilled assembly-line operations, activists were approached by workers for help – many had not been paid their monthly wage.

As P.K. Chamilla Thushari from the Da Bindu Collective recalled:

“… [their] children cried asking for food. Many [workers] called us saying they had nothing to eat. This was a new experience for us …”

The organisations rapidly turned to their networks, and organised emergency food aid. They also distributed hygiene and sanitary kits. They reached across ethnic and geographical borders to also deliver food aid in the northeast, and in the case of the Women’s Centre, cash vouchers in the north.

The women’s groups also worked with the Ministry of Health, public health inspectors (PSIs) and area midwives to access and distribute health information. The organisation reported having to lobby state officials and employers for protective gear such as masks in workplaces.

They were a part of tripartite discussions to ensure workers were paid. They continuously lobbied various power holders – from the Board of Investments, to the Prime Minister, Minister of Labour, and employers. The Stand-up Movement lodged a petition with the Human Rights Commission.

The women’s organisations drew on existing strategies and networks. The Standup Movement held a picket in front of the free-trade zone gate. The Women’s Centre, Da Bindu, and the Standup Movement worked on the Asian Floor Wage Campaign, and with the Clean Clothes Campaign to research, document and draw international attention to dismissed workers.

Padmini Weerasooriya from the Women’s Centre) said they:

“… had to struggle a lot to keep the factories from closing down …”

They supported and worked with local and international trade unions as well, and local groups such as Mothers and Daughters of Lanka. Funders (for example, War on Want, Asia Foundation) enabled them to divert existing funds.

When reviewing the global updates provided by the Clean Clothes Campaign, one is made aware of the vast global network of grassroots women leaders and activists who have been at the forefront of promoting and defending workers' rights in the global garment industry, from Myanmar to Cambodia and, of course, Sri Lanka.

Although they may be overlooked, they're demanding to be heard, and are driving change. Perhaps their leadership during the pandemic can best be summarised by the Stand Up Movement’s slogan stitched into their masks: "Mask Yes. Silence No!"