A Monash research report launched this week recommends significant reforms to improve the culture and practice of administering access to government information, including a shift to a more modern “push model” that emphasises proactive release, with reliance on FOI requests as a last option.

It also emphasises the significance of severe underfunding of FOI teams and inadequate records management as bottlenecks to a well-functioning access to information systems.

The report is the outcome of an extensive three-year investigation into the culture and practice of administering the FOI Acts across the states of Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia.

The project was funded by the Australian Research Council, and conducted in collaboration with the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC), the Ombudsman South Australia, and the Office of the Information Commissioner, Western Australia (OICWA).

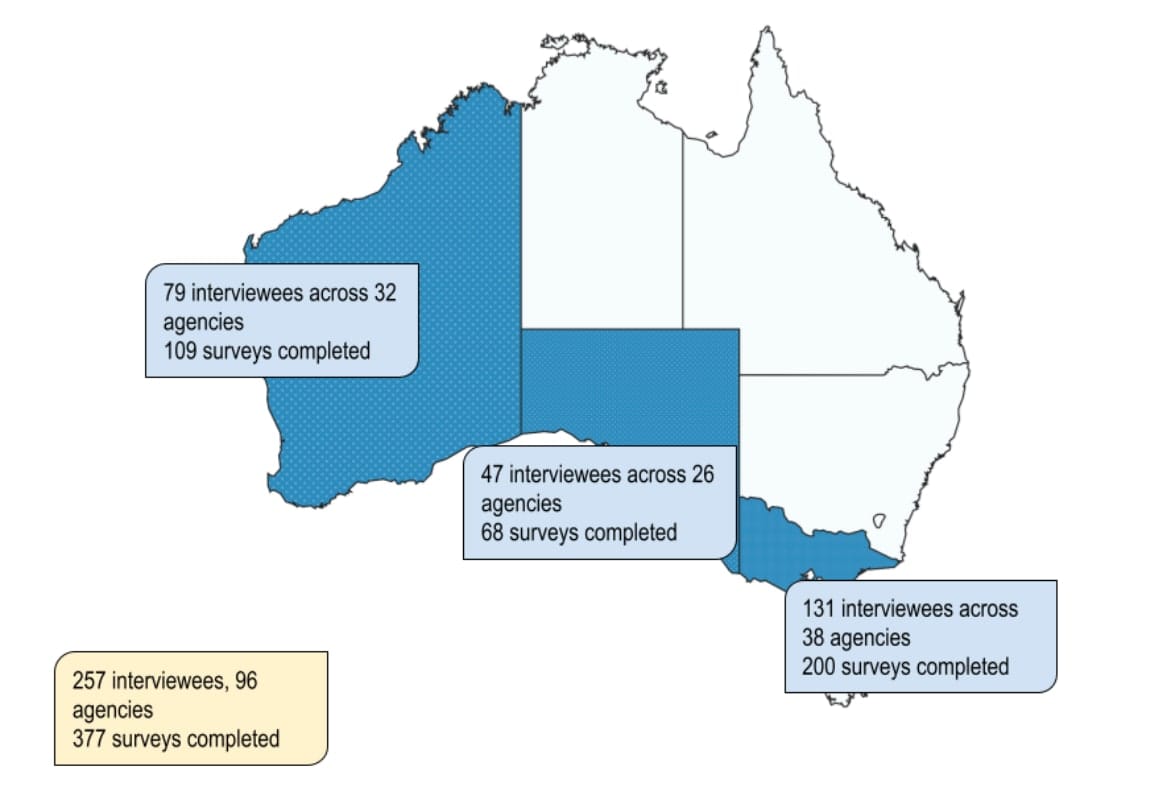

The project was based on surveys and interviews of three cohorts – FOI officers and managers, government agency executives, and government ministers – with a total of 257 interviews and 377 surveys conducted across 96 agencies.

The response rates to the surveys were very healthy (86% in Victoria, 62% in South Australia, 74% in Western Australia), although there was a notable absence of participation by government ministers.

Proactive push model

Our first group of recommendations are for legislative reforms to the FOI Acts to formally enshrine a proactive push model, ensure their terminology and procedures are reflective of modern digital environments, and make practical changes to address issues that currently hamper the work of FOI practitioners.

The key legislative reform recommended is making explicit that proactive release be the norm, with the need for FOI requests as a last option. This would go a long way in improving transparency by creating a more explicit pro-disclosure approach to information release.

Other recommended legislative changes focus on aligning timelines with working days, streamlining consultation requirements, and addressing the problem of vexatious applicants.

Our data shows the great majority of FOI officers are knowledgeable, passionate and keen to act as facilitators of information access, and that they require further practical assistance to achieve their potential in furthering the aims of FOI laws.

FOI law administration

Our second set of recommendations relate to the ways in which FOI laws are administered. They encompass not only FOI, but also records management, and include recommendations for improved education and training.

In terms of FOI, we recommend that regulators support agencies in developing proactive release policies relevant to their needs. It’s clear that many FOI practitioners would benefit from clearer guidance concerning proactive release, and that initiatives such as OVIC’s proactive release template policy can play an important role in influencing the culture to make FOI work better.

Read more: The whistleblower: A hero pursued rather than protected?

We also recommend that they play a more active role in ensuring any ministerial noting processes are structured to ensure that FOI officers can process requests within required timeframes.

The interviews with FOI officers found some evidence that ministers’ offices at times abuse the noting process to slow down information release in the case of potentially controversial FOI requests.

Records management is vital

Our other recommendations reflect our findings that good records management is vital to the operation of FOI.

Unfortunately, people’s eyes glaze over when records management is mentioned. It’s not a “sexy” topic, but it sits at the core of good governance and well-functioning FOI. If you can’t locate the information, you can’t release it to the public.

We recommend that the rollout of records systems is consistent with both records management best practice and FOI efficiency, and that regulators collaborate to ensure agency adherence to record keeping requirements and strengthen the knowledge and understanding between records management best practice and FOI efficiency.

Bringing FOI and RM into the digital age will require an all-of-government holistic approach requiring a major funding boost and political will. Unfortunately, the disinterest from government ministers in engaging with this study is not encouraging.

Of the 55 ministers (25 in Victoria, 15 in SA, and 15 in WA) only three (two in SA and one in WA, none in Victoria) engaged with the study. This is deeply disappointing.

Those with, potentially, the most influence over improved functionality of FOI are simply not interested. By this the governments also forgo the opportunity to use a well-functioning FOI regime as a tool to rebuild trust in government.

Shift in FOI attitudes

This takes us to the final point to be made, and one of the main takeaways from the report. This is the most comprehensive study to date of FOI culture in Australia (and globally, one of the most comprehensive). There’s no point in replicating this study in other jurisdictions, as previous studies point to the conclusion that we would generate very similar findings.

Legal and functionality studies of FOI go back to the 1990s – this is now a well-researched area of governance and policy. We’ve seen some improvement over time, including a shift from the “government owning the information” to “holding information on behalf of citizens”.

We confirmed this shift in attitudes has informed FOI culture on the part of FOI practitioners.

What the ministers think, we still don’t know. A recent indication (Victorian budget 2023-24) of what the Victorian government thinks about the importance of access to information is that the OVIC’s budget has been cut by 19.5% for the next four years, severely hampering the agency’s ability to oversee and assess FOI appeals.

A further indication of the future of FOI in Victoria will come when the parliamentary inquiry into the operation of FOI reports later in 2024.

What we do know is what needs to be done to improve the information access systems in Australia, creating a more accountable governance environment and powering the growth of our digital economy.

Encouragingly, the OVIC, Ombudsman SA and OIC WA have accepted the recommendations in our report, and will work to implement them.

The chief investigators would like to acknowledge the crucial contribution of the other members on the research team: Dr Erin Bradshaw, lead research assistant; Sarah Davison, research assistant, South Australia; and Mary-Anne Romano, research assistant, Western Australia.