Despite the political debate that has ensued around the Voice proposal, the choice of an institutional advisory body that informs Parliament and the executive government is entirely unremarkable.

It is a modest proposal. We barely cast a glance at the work of the Productivity Commission or the Australian Law Reform Commission, both of which are mainstream advisory bodies to the national government. They inform law-making; their advice may be considered, or not.

Similarly, the Voice to Parliament will have the capacity to inform policy and reform, but it is not a third chamber of Parliament.

It will not make laws or distribute funding. It will not undertake program delivery. It will have no veto.

The Bill that amends the Constitution makes it clear that “The Parliament shall have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures”. Parliament retains control over the way the Voice works.

Despite the myriad positive consequences of the Voice, many myths and much misinformation has been propagated about it.

Certain concerns that have arisen at the time of writing will no doubt have dissipated with greater understanding of the proposal, while a number of counter-claims regarding the Voice have no foundation, as countless constitutional experts have testified.

A Voice to, not in, Parliament

To be clear, what is proposed is a Voice to Parliament, not a Voice in Parliament. It will have no role in passing legislation; that will remain in the hands of elected representatives in the federal Parliament, as required by the Constitution.

The Voice can make representations to Parliament, but it will be up to Parliament to decide what it does with those representations. It should pay attention to them, but it will always take into account a wide range of advice from across the community.

The Voice does not create special rights for Indigenous people or give them a veto – it just establishes an advisory body.

Read more: It’s a date: Now the referendum’s set, we need to focus on the facts

Parliament will be better-informed about the impact of proposed laws on First Nations peoples, and can amend its laws where that is appropriate. So, for example, it will inform how Closing the Gap and other initiatives can best work to improve outcomes.

The Voice will not damage our democratic institutions; it will enhance them. It will not “put race into the Constitution”, as the Constitution already allows for racially discriminatory laws by virtue of section 51(xxvi) (the race power).

It will ensure that the silence and omissions of the past can be addressed in the future. It cannot be racist to address racism.

A negative result means a loss of credibilty

A “No” vote is not a vote for the status quo. It will not have the effect of keeping the arrangements for managing Indigenous affairs as they are now.

Rather, a negative result in the referendum will mean a loss of credibility, at a number of levels. It will amount to the end of reconciliation advocacy for many Indigenous leaders and their supporters.

As Palawa scholar Ian Anderson put it in an opinion piece, a failed referendum will “spell the end of the long reconciliation walk”.

Ian Anderson’s view is shared by many who have focused their efforts on developing coherent and constructive advocacy for Indigenous recognition.

Noel Pearson says he will “fall silent” if the referendum fails, adding: “If the advocacy of that pathway fails, well, then ... a whole generation of Indigenous leadership will have failed, because we will have advocated coming together in partnership with government, and we would have made an invitation to the Australian people that was repudiated.”

‘Racists will feel emboldened’

But a loss will reverberate in other ways. Professor Marcia Langton states it clearly in the title of a recent article: “If yes campaign for Indigenous voice loses, ‘racists will feel emboldened’.”

We’ve already watched aghast as leading Indigenous journalist and media identity Stan Grant stepped away from his national role on the ABC’s flagship Q+A program, pointing out the impact of corrosive racist discourse.

We have already seen some mainstream and social media debate about the Voice referendum become divisive and hostile to Indigenous people, with abusive racism deployed to attack the proposal.

An unsuccessful referendum will mean that, instead of moving towards a more united, mature and thoughtful nation, we will see greater division and disrespect.

Read more: Voice to Parliament: Debunking 10 myths and misconceptions

There is, unsurprisingly, disagreement about the proposal across Indigenous communities, although opinion polls suggest most Indigenous community members support the Voice.

It’s important we respect differences of opinion and recognise that there has never been one unified Indigenous point of view. As we would expect when discussing hundreds of different cultures, there will always be divergences along with alignments.

Ian Anderson notes that “most Indigenous Australians who don’t support the Voice do so because they think its ambitions are too modest. They do not think governments can or should be trusted.”

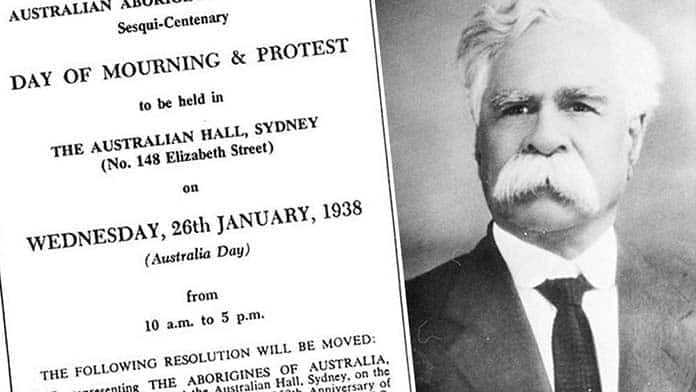

Indeed, past experiences such as the Howard government’s abolition of ATSIC and the Hawke government’s failed Makarrata process suggest that, by and large, governments can’t be fully trusted.

This is why proponents of the Voice are clear that they will need to be ever-vigilant. This is the very reason the Uluru Statement calls for constitutional recognition and permanency, not merely an Act of Parliament.

A modest first step – but a vital one

To those who seek more than the Voice, believing it falls short because it does not put in place treaty arrangements or a truth-telling commission, we say we agree. It is a modest first step.

But if this step falters, the other steps will not occur. There will be little political or electoral will to pursue the agenda set out in the Uluru Statement, and all aspirations for justice and proper legal relations with First Nations peoples will be delayed indefinitely.

It has been a long wait, but now is the time to listen, to truly hear, acknowledge and accommodate.

The Voice to Parliament shifts the relationship between First Nations peoples and the state from a monologue to a dialogue, from unilateral to multilateral, from a majoritarian agenda to a consultative and participatory one.

This recognition and relationship are not just essential for First Nations, but are fundamental to Australia as a constitutional democracy. The referendum to entrench it in the Constitution is unequivocally in the national interest.

This is an edited extract from the book Time to Listen: An Indigenous Voice to Parliament, by Melissa Castan and Professor Lynette Russell, published by Monash University Publishing.