A recently-opened exhibition on the Indonesian Revolution at the Dutch Royal Museum (Rijksmuseum) in Amsterdam could represent another step towards enhancing friendship between two former foes.

The Indonesian government lent support with loans of materials for display, while the museum invited two Indonesians to join the team of four curators.

Alas, before it even opened, the exhibition suffered a backlash. The curators faced two opposing legal complaints in the Netherlands.

The incident was sparked by debate over the use of the word bersiap, following a strong objection from one of the Indonesian curators – historian Bonnie Triyana – via an opinion article that appeared in the local press.

Bersiap (literally, “get ready”) is commonly used with a narrow political sense, referring to “anti-colonial” mass violence inflicted by the colonised against Dutch colonisers and their assumed allies.

Adopting a similarly narrow sense, Bonnie argues that the use of the word is racist. However, with detailed evidence, other historians show such a narrow view of bersiap is deeply problematic.

Although the Dutch public prosecutors dismissed all the legal complaints last week, the incident demonstrates how major violence in the past continues to haunt the two nations. It can neither be completely erased from public memory, nor discussed openly without stirring emotional reactions.

Bersiap: a complex and muddled history

Key to understanding the protracted problem is examining a powerful but dangerous dichotomy that paints the Indonesian-Dutch history as “good versus evil” or “us versus them”.

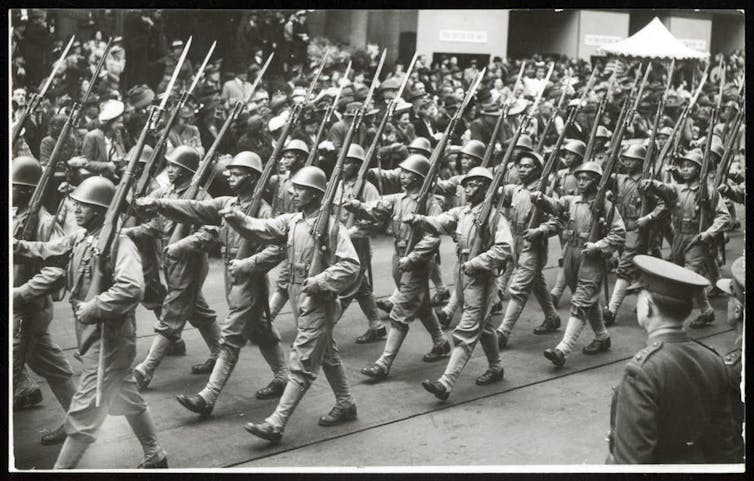

The dichotomy oversimplifies the period of chaos and violence between the end of the Japanese occupation (1945) and the establishment of social order in independent Indonesia (1950). It erases important events and people in this period that do not fit either of the two opposing categories.

One of the clearest examples of this problem is the fate of Eurasians (children of mixed European-local parents), often called Indo in Indonesia and Indisch in the Netherlands. This community was a primary target of the violence of bersiap, yet are often forgotten amid the Indonesian-Dutch blame game.

To this day, such a remarkably strong nationalist sentiment prevails in Indonesia.

In reality, the perpetrators of bersiap, along with their motives and victims, are diverse and not always easily identified.

In addition to political acts, there appears to be a mix of many things – racial hatred, sexual violence, looting of valuable items, along with social and class tensions – instead of purely political or racial sentiment.

Most accounts of the incident identify “Indo” as the main targets of bersiap. Others suggest the number of victims among local Indonesians might be greater.

As in other contested politics, there are open-minded Indonesian and Dutch citizens who are aware that human history is never a caricature of good and evil. However, as with most controversies around the world, those with extreme views often dominate the public debate.

The Dutch public is also diverse in its responses to the bersiap controversy. Yet such diversity of views often gets lost in most Indonesian media reports and the discussion they generate.

Bersiap is only part of a bigger story of mass violence during the 1940s. The latter itself is part of a bigger story of centuries-old colonialism and decolonialisation.

What makes bersiap slightly distinct is its absence in the official histories of both the Netherlands and Indonesia.

Diverse Indo communities

As long as the dichotomy of Indonesia/Netherlands dominates public discussion, the Indo people will once again become victims.

Their distinct identities of being in-between, as well as partially both Indonesian and Dutch, are either erased or oversimplified and misrepresented.

The Indo community has always been politically and culturally diverse in orientation.

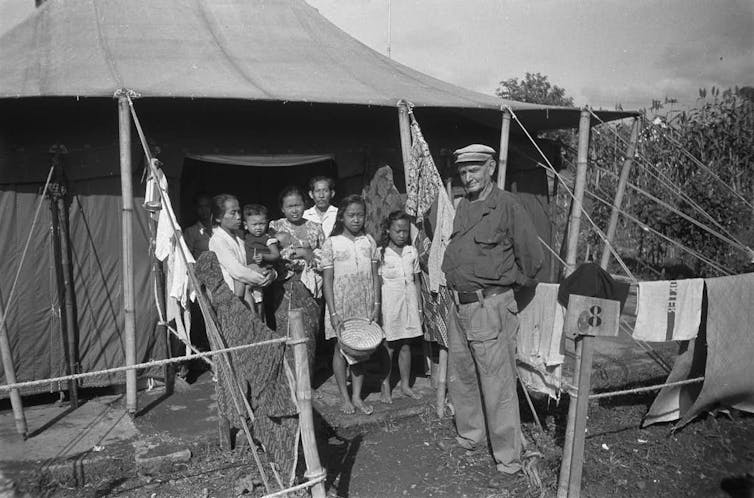

The mass violence in the 1940s dispersed them globally and made their sense of identity even more diffuse.

Despite such diversity, memories of bersiap remain one of their painful but unifying points of reference and sources of identity. This is in addition to their nostalgic memory of the good old days (dubbed “tempo doeloe”) in the Dutch East Indies.

Fleeing from Indonesia during bersiap, about 300,000 people with “European” status, mostly Indos, sought refuge in the Netherlands. Some remained in Indonesia either by their own free will or lack thereof.

Those landing in the Netherlands didn’t feel warmly welcomed. They and their descendants were neither “Indonesian” nor accepted as “adequately” Dutch. Later, some of them migrated to the US and Australia.

Neither the Netherlands nor Indonesia has managed very well to get rid of the colonial legacies of racial politics and the modern fantasy of ethnic or racial “purity” and “authenticity”.

In Indonesia, nationalist nativism renders Indos as categorically “Dutch”. Within the widely held dichotomy of “us/them”, they are seen as belonging to the coloniser camp.

Individual Indos appear in public life in Indonesia in various fields, although they are most prominent in the advertising and entertainment industry.

Apparently, however, they’re not formally organised, unlike those in the Netherlands, the US or Australia. Also in contrast to Chinese, Indian or Arab ethnic communities in Indonesia and neighbouring countries, Indonesian Indos do not hold public events nor celebrate their distinct cultures.

From interviews with some Indonesian Indos before the pandemic, I get the impression that the trauma of bersiap, plus a nationalist militancy in the country, make it nearly impossible for them to do much about their history and cultural heritage. I sense a kind of resignation, as most of their children and grandchildren have neither the knowledge nor curiosity about their past.

Lessons for the next generation

Every nation has its own dark past, and their younger generation must bear the consequences.

Only some nations have boldly made attempts to look back and start learning to come to terms with such pasts. Despite the pain and noise it’s caused, the Netherlands has taken overdue steps to confront its past wrongdoings. The world is watching.

Hopefully, important lessons will be learned from the Netherlands’ endeavours, its challenges and achievements.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.