The Citarum is the longest and largest river in West Java, running 270km through thousands of communities to connect the people, villages and landscape of the most populous province in Indonesia.

It supports the food, water and electricity supply for 25 million people, irrigating hundreds of thousands of hectares of rice fields, and supplying the nation’s largest reservoir.

It’s also one of the most polluted rivers in the world.

With more than 25 million people living in its basin, and thousands of waste-producing factories based along its course, this living spine has been put under immense pressure by industry and human activity.

Read more: Turning dirty water clean: Portable water filter to aid disaster relief

Water quality across most of the river has been deemed unsafe for human use, with the Asian Development Bank finding levels of faecal bacteria more than 5000 times the mandatory limits, and lead levels far exceeding the US Environmental Protection Agency drinking water standard.

The implications for those living in informal settlements along the river are enormous, with nowhere to dispose of rubbish, no sanitation, and no choice but to use the only water available to them. It’s an impossible symbiosis, and one mirrored in vulnerable riverine communities and ecosystems across the globe.

In 2018, the Indonesian government established the Citarum Harum – a seven-year river revitalisation program with the goal of making the Citarum’s water drinkable by 2025. No small challenge, but one that has some significant backing.

The program has been supported by the International Monetary Fund and the Asian Development Bank, and includes reforesting surrounding mountains, extracting toxic sediment, regulating wastewater discharge, and environmental education projects.

Soldiers have been cleaning allocated sections of the river, and installing rubbish and water treatment facilities. Local universities and environmental agencies have been working to address the sources of contamination, and investigating solutions.

Read more: Lessons from Indonesia: How scientists and communities can build partnerships

But even with this top-level commitment and funded infrastructure, profound environmental and human challenges remain.

Over the past decade, Monash University has been forging alliances with local governments and agencies to better-understand and help transform systems for sustainable development in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region.

Read more: Restoring a forgotten river in Subang Jaya, Malaysia

This includes a unique action-research model that sees interventions implemented, and generates scientific evidence on the impacts of those interventions – evidence that policymakers can use to drive more inclusive policy and investment, especially for underserviced communities.

In 2018, Monash and Universitas Indonesia were invited by the Governor of West Java, H.E. Ridwan Kamil, to contribute ideas to support the Citarum Harum and the Citarum Satuan Tugas (SATGAS) – the taskforce leading the Citarum action plan.

Since then, researchers across six Monash faculties and institutes (Art, Design and Architecture; Monash Sustainable Development Institute; Arts; Business and Economics; Engineering, Law; and Science) have been collaborating with Universitas Indonesia, the Indonesian government, communities, local NGOs and the global research community to create a transdisciplinary approach to river transformation.

The diverse and cross-disciplinary thinking spans and integrates urban design and design thinking, urban transformation through water-sensitive city and circular economy approaches, and sustainability transitions theory through social innovations and experimentation.

To create a healthy river corridor and healthy communities, we’re now imagining a new paradigm for river governance, where a river is viewed as an ecological spine that:

- delivers ecosystem services

- supports local, circular economies and livelihoods, and

- is the foundation of resilient, inclusive and healthy communities.

By bringing together urban design and sustainability transitions theory, we aim to create an urban transformation model that restores waterways, provides water, sanitation and solid waste services, generates sustainable micro-circular economies, and creates resilience to climate change and natural disasters.

In close partnership with the West Java government, we aim to upscale this model to the broader catchment.

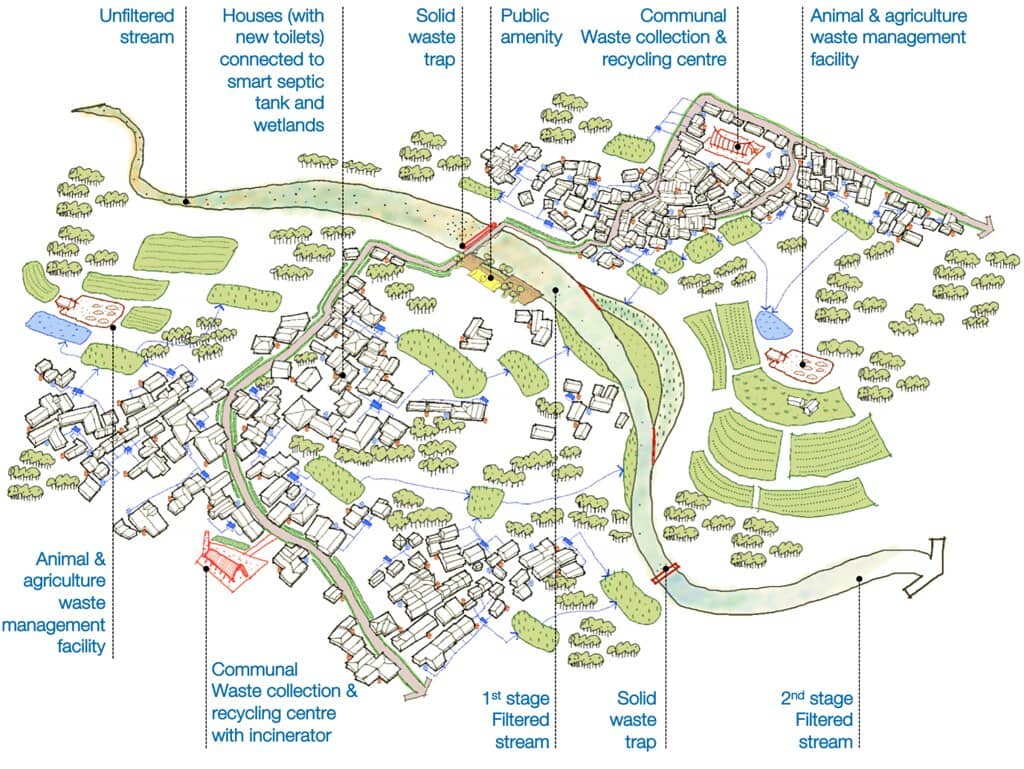

The next step is to demonstrate this new paradigm in a riverine village in the Citarum basin, in a type of “living lab” where we work with local communities, local experts and academics to co-design and test solutions that capture and treat wastewater and solid waste, and create value from locally-derived waste streams in a closed loop system.

Co-design, testing and evidence generation in living community contexts draws on our research and experiences with the Revitalising Informal Settlements and their Environments (RISE) program.

RISE works to improve human, environmental and ecological health in 12 informal settlements in Makassar, South Sulawesi, and 12 informal settlements in Suva, Fiji, to inform slum upgrade programs across the developing world.

Read more: RISE Indonesia: Revitalising informal settlements in Makassar

In this context, RISE applies a novel approach to water management, using nature-based infrastructure (such as constructed wetlands) to treat grey and black water from households before it’s either recycled or discharged into the environment.

The Citarum “living lab” will leverage the work of the RISE consortium and build a new international coalition of researchers and experts, with experience in aspects of informal village-scale water and waste solutions, who can come together to work with selected communities on a holistic approach to river transformation, test this concept of an ecological spine that connects people, villages and landscapes, and generate evidence and knowledge for scaling.

Just before the coronavirus pandemic struck in February 2020, Governor Kamil visited Monash Art, Design and Architecture at Monash’s Caulfield campus, endorsing our concept and agreeing to a pilot in a cluster of villages along a 2.5km Citarik River corridor – a tributary in the Citarum River basin.

While our endeavours were delayed by the COVID crisis that followed, the pandemic has reinforced how critical water, sanitation and solid waste solutions are to community health and wellbeing, and economic recovery.

There’s now a shared understanding that the long-term restoration of the Citarum catchment is an intergenerational challenge, requiring a multi-sector, transdisciplinary approach based on genuine, ongoing engagement with the communities living along the river.

This understanding was recently formalised, when Monash University’s Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Vice-President (Global Engagement) Professor Abid Khan and Governor Kamil signed a letter of intent for our future work together.

This marks an exciting phase in the Citarum Program, enabling us to work in concerted collaboration to develop co-designed solutions that breathe life back into the Citarum.

Transdisciplinary research endeavours such as this will generate evidence for river restoration and transitioning riverine communities towards circular and restorative economies – which will pave the way to transform watersheds across Indonesia and Southeast Asia over the coming decades.

Professor Diego Ramirez-Lovering is Director of the Informal Cities Lab at Monash Art, Design and Architecture, and Director of the Citarum Program, working alongside Professor Rob Raven, Dr Jane Holden and Professor Tony Wong of the Monash Sustainable Development Institute.