Rigid stereotypes exist about victim-survivors from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities. Migrant woman victim-survivors are frequently misunderstood, discriminated against and stereotyped as passive victims by the system and wider society.

During my fieldwork, I met Ari*, a Korean victim-survivor who had migrated to Australia in the late 1970s.

Ari is a daughter of a first-generation Korean-Australian and a working professional who supported her family as the primary earner. Before she left her partner, they were together for eight years, and the couple share one child.

Ari, similar to other Korean women I’ve met, however, made her own decision to leave the violent relationship when she felt safe to do so.

Being the primary earner

What I learnt from Ari’s lived experience is that her status as the main breadwinner didn’t challenge or shift patriarchal practices within the home. The domestic and family violence (DFV) in the relationship was accompanied by the dominant features of power and control.

This was also the case for other Korean women who made more or equal economic contributions to the household and who had experienced DFV.

Having more financial resources made Ari and the other women’s transitions smoother when they decided to escape their ex-partners, because they didn’t need to access a shelter or social services, as they had the means to find alternative accommodation.

Despite this, their stories revealed that DFV amplified their experiences of social isolation, and led to loss of employment and housing instability in the long run due to relocation.

Intersection of economic resources, diasporic communities and displacement

There’s an emerging view that women’s relocation to escape from violent partners is forced internal migration due to its gendered and involuntary nature – if it weren’t for DFV, women wouldn’t have needed to relocate to other areas.

All the victim-survivors I’ve met resettled in another suburb or state after separation, while the majority of the perpetrators stayed in the same suburb or close to where they lived. Women have fewer options, but choose to relocate despite the risk of being further isolated from their original/diasporic communities.

For victim-survivors, the small size and the intimacy of the diasporic community may lead to women having unwanted interaction with perpetrators or facing rumours about their families, which can re-traumatise them despite fleeing the perpetrator.

Ari’s ex-partner, Jiho*, also moved close to Ari after separation in order to pursue his career, which resulted in Ari once again choosing to move to another state in order to avoid close contact with him.

The consequences of the end of violent family relationships continue to disproportionately impact victim-survivors long after their escape.

Having a social network should not be translated as having social support

Most Korean victim-survivors in this research were made more vulnerable by their lack of support networks, such as families and friends in Australia.

Korean diaspora victim-survivors in Australia’s experiences are impacted by both their Korean background and their diasporic context. When considering the effect of cultural factors on diasporic women’s experiences, we can’t focus purely on the influence of their native culture. We also need to consider how it interacts with the culture of the diasporic community in which they currently live. These intersecting cultural influences create the social context victim-survivors navigate.

The narratives of the Korean victim-survivors highlight the fact that having a social network may not always work in the women’s favour, due to the nature of patriarchal culture and the presence of gender policing within the diasporic community.

In Ari’s case, when she reported her ex-partner to the police, Ari’s father was angered at her ex-partner’s misconduct, but also criticised his unwillingness to support the family as a breadwinner. It was more important for him to be the primary breadwinner as opposed to not being violent.

At the time, Ari’s father’s attitude made her stay in the violent relationship longer.

The Ari Project – how it all came together

As a qualitative researcher who works with marginalised populations in Australia, I understand not all victim-survivors or members of CALD communities may have access to scholarly work. Together with Jun Bin Lee (a film director and composer), I decided to transform the narrative of Ari into a three-part video series to go beyond teaching and research, including the dissemination of knowledge to other parts of Australian society.

This was also my way of giving back to the Korean community, and the broader community outside of academia.

Throughout this cross-industry project, we organised two feedback sessions with Korean-Australian practitioners and researchers to ensure we didn’t misrepresent the Korean victim-survivors and the Korean-Australian communities.

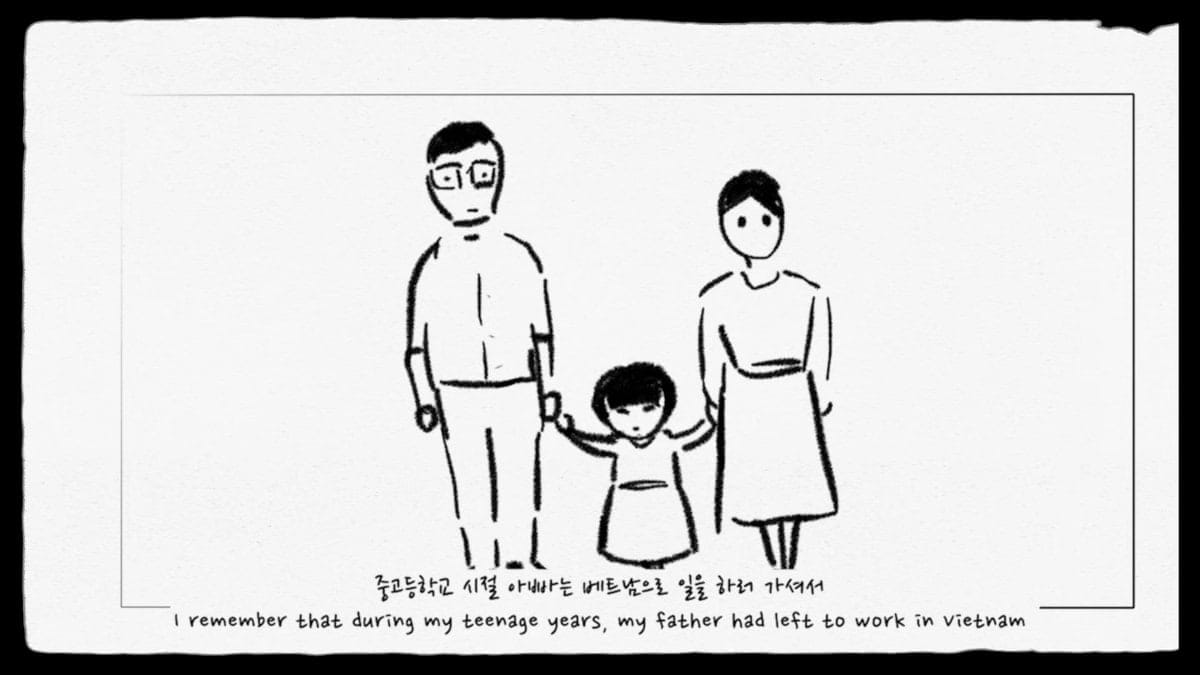

Part one: Migration (animation)

The first part of this series uses animation to capture Ari’s migration to Australia, and how she met her ex-partner, Jiho, in Australia.

Part two: Trap (music video)

The second part focuses on her lived experience of DFV, and is presented as a music video. The lyrics were written based on her real descriptions of her experiences, as quoted from my in-depth interview with her.

Part three: It’s Not Your Fault (dance video)

The final part uses a dance video to encapsulate how Ari navigated her post-crisis journey – liberation, peace, anxiety, and fear.

In this last part of the video series, we wanted to show that leaving the violent partner doesn’t mean the end of the DFV ramifications.

Perceptions can hinder access to services

Negative perceptions of victim-survivors from CALD communities can ultimately act as a barrier to accessing services for those experiencing DFV.

In reality, their DFV experiences are often a series of patriarchal (re)negotiations with their violent partners, sometimes with multiple perpetrators’ interests in the transnational context.

We hope this project can highlight Ari’s resilience, capacity, and agency as manifested in her narrative, and to defeat the common stereotypes surrounding Korean victim-survivors that exist within broader Australian society.

*All names appeared on this article are pseudonyms.The video series and other relevant resources will be made available freely for education and training materials at theariproject.com after online screenings on 10 March, 2022. This project has received production funds from Creative Victoria, and publication funds from the Freilich Project for the Study of Bigotry at the Australian National University.

This work was supported by the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies