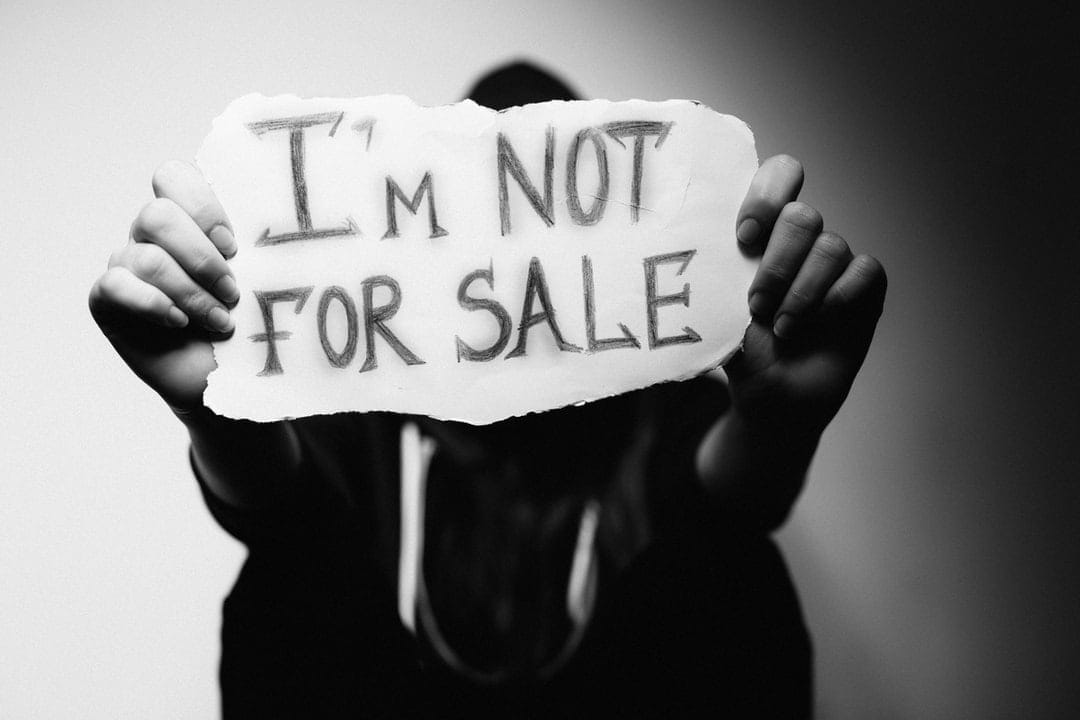

During these 16 days of activism against gender-based violence, the consistent call is not just to acknowledge gendered violence, but to look into how we can change the world and make it safer.

Across Australia, there's well-established evidence about the need to make substantive reforms to better support and protect women experiencing domestic family violence (DFV) who hold temporary visas. Indeed, in the wake of the 2020-21 federal budget, the acting Minister for Immigration, Alan Tudge, upheld the importance of supporting all women who experience abuse, stating:

"It doesn't matter who you are, where you come from, whether you are here on a visa or have Australian citizenship – no one should be trapped in a violent relationship."

This is an important statement, and one that service advocates and researchers have been emphasising for some time.

There is, however, limited action.

The budget response to "protection" for women was to make partner visas less accessible.

It included, for instance, that partner visa holders applying for permanency in Australia have a “functional level” of English.

Partner visas are the only visas with a safety net that ensures women who experience DFV can access ongoing financial, housing, legal and other support, and remain on their pathway to permanency.

The introduction of this kind of change to the accessibility of the visa implies that women hold risk because of their lack of English language proficiency. Real change to women’s safety cannot be realised via this proposed strategy.

In the efforts to achieve change nationally, there has been advocacy across the nation, led by members of the National Advocacy Group on Women on Temporary Visas Experiencing Violence. These efforts have been persistent, with various members meeting with local and state leaders, as well as Commonwealth leaders, and sharing research findings and data related to service provision.

However, in advocating for reform, a consistent brick wall has been the persistent question of how "big" the problem is.

Quantifying how many temporary visa holders are experiencing DFV is methodologically complex. Temporary visa holders are by their nature in the country in a dynamic and transitory way.

Agencies, including the police, do not collect migration-related data, and this is important and should remain this way, because we know that many people fear reporting their experiences of violence to police, and that many people on temporary visas who experience any form of violence and abuse, including DFV, will be threatened with the consequences of reporting to police.

A national figure on the proportion of women who hold temporary visas who are experiencing DFV will always be an estimate.

Is the number the real question, anyway?

What difference can quantification make? If we say 10% or 25% or 75% of temporary visa holders experience DFV, which number is important? Which number is enough to lead to change?

In 2003, the then attorney general announced a commitment of $20 million to addressing human trafficking in Australia, specifically sex trafficking. The year before, human trafficking had essentially been rejected as a major issue in Australia; there were a "handful" of cases, and the push for reform was dismissed. Twelve months later, with still only a small number of potential victims, new legislation and victim support was introduced alongside the creation of a specific victim/witness visa. Why share this example?

Across two studies in three years, in 2017 and in 2020 (with Pfitzner), the situations of 400 women on temporary visas seeking support in Victoria have been examined, and the specific areas for reform to improve women’s safety identified.

Still, the question is how big this problem is. Compared to the response to human trafficking, where the numbers of potential victims was estimated to be around 10, these two studies alone highlight the specific situation of 400 women from Victoria alone.

Waiting on a number is a clear misdirection. The politics of how we treat temporary migrants is important.

The COVID effect

During COVID-19, the federal government’s decision to lock temporary visa holders out of the JobKeeper and JobSeeker financial safety net had significant ramifications across the community, in relation to labour exploitation, precarious work, and poor and risky working conditions leading to worker deaths, and in relation to women experiencing DFV, with an even greater reliance on abusive partners in the context of lockdowns and stay at home orders.

It has been well documented that for temporary migrants the message is clear: go home, Australia is not responsible for you at this time. What little support has been made available has been piecemeal.

When it comes to domestic and family violence, the message is similar – piecemeal, short-term support may be accessed, depending on your visa status. Despite the clear evidence based on hundreds of cases that this puts women in a situation where their options are limited, and where they may be forced to remain with abusive partners, there's little movement on substantive reform that will enhance women’s safety.

The forms of gendered abuse and exploitation that temporary migrants experience, including, but not limited to, DFV, will not be addressed through piecemeal campaigns and platitudes. These are system-level problems that require the lens of women’s safety to be our foremost concern if we want to achieve real and impactful change.

During these 16 days of activism, the challenge is for policy to move towards demonstrating that Minister Tudge’s commitment to ensuring no one is trapped in a violent relationship translates into reform that will actually ensure that no one, regardless of their visa, is trapped in a violent relationship.