Recurrent pandemic-induced lockdowns in Australia have been met with expressions of resignation and frustration, along with anger and despair.

The highly infectious Delta variant has called for measures that have taken many people to the brink, with a huge toll on mental health.

The lockdowns have corresponded with an overall increase in the use of crisis lines such as Lifeline and mental health services since 2019, and evidence of psychological distress, especially among younger people.

Read more: Double trouble: How severe lockdown restrictions have taken a toll on population mental health

Such statistics, however, provide but a snapshot of a wider picture of social distress and expressed “loss of hope” that has accompanied economic and social disruption.

In news reporting on the lockdowns, many individuals, including small business owners, often say that they “lack hope”, which is related to disruptions and uncertainty about the future.

Hope as the antidote to despair

Scholars have long recognised the significance of hope for survival and motivating actions.

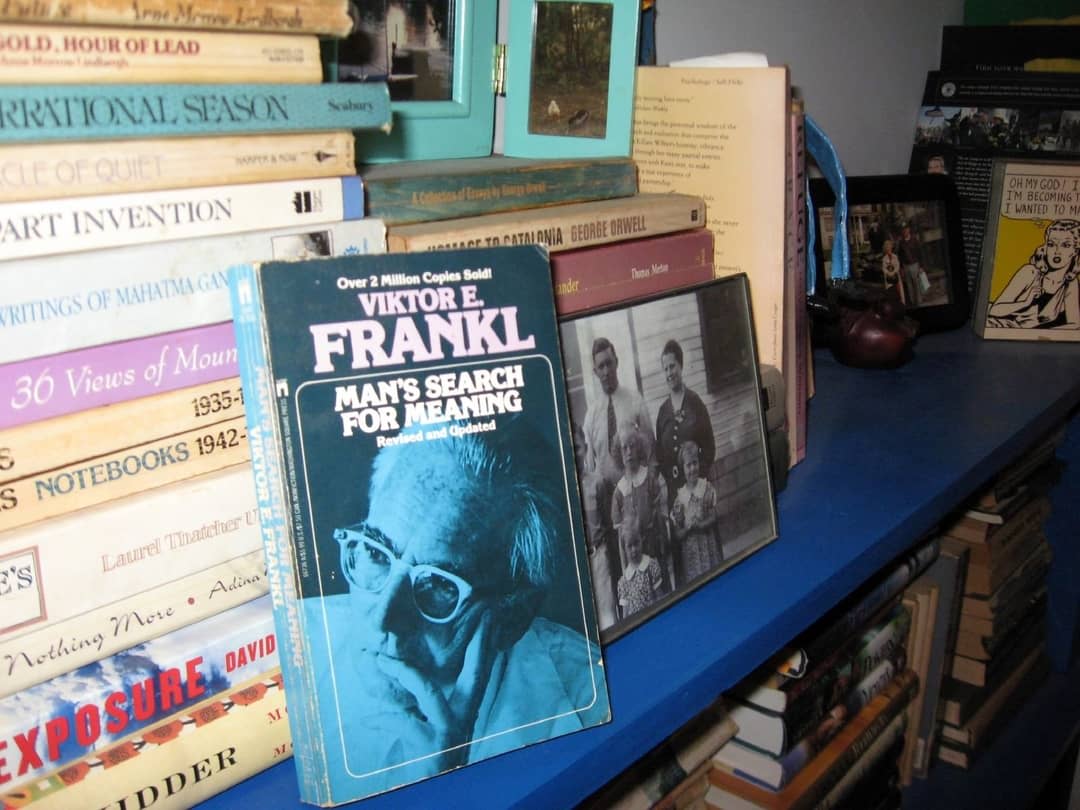

Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor, wrote about the power of hope in Man’s Search for Meaning. He observed that life has meaning, even in contexts of despair, and that the way prisoners imagined the future affected their prospects for survival.

It’s noteworthy that the seminal writings on hope, such as Ernst Bloch’s three-volume The Principle of Hope, and Erich Fromm’s The Revolution of Hope, were written in contexts of despair and uncertainty – World War II, and the Cold War and the prospect of nuclear annihilation, and the complete mechanisation of society, respectively.

These writers saw hope as the antidote to despair. They recognised that hope is active and productive in that it entails (as Bloch put it) “venturing beyond” the present, to visualise the possibilities of an imagined better future world.

In my own work on hope in the context of medicine and healthcare, I’ve uncovered the significance of hope in shaping actions.

Among patients who have exhausted conventional treatment options, hope sometimes leads patients to pursue treatments that may seem promising but are clinically unproven, such as stem cell therapies.

Health professionals often aim to “instil” hope in patients in the belief that the possession of a positive outlook assists with their recovery.

However, hopeful pursuits may not always prove beneficial. It may be based on a false premise and belief in the value of interventions, the safety and efficacy of which aren’t supported by credible evidence.

These “false hopes” may be shared by whole communities, and guide policies and practices. An example is the case of a promising new treatment for breast cancer, involving high-dose chemotherapy combined with autologous bone marrow transplantation, which ultimately proved ineffective.

Throughout the pandemic, hope has strongly attached to science and technology, especially to vaccines, which promise to deliver freedom from disease and death, and enable people to resume some sense of normality in their lives.

Contemporary discourses of hope are, unfortunately, dominated by the perspectives of positive psychology and psychotherapy, which has restricted our understanding of hope and its potential.

These focus on individuals rather than social processes, and assume that the possession of a “positive outlook” is necessarily “empowering” and beneficial for individuals.

Scholars in these disciplines have mostly ignored the valuable insights offered by the classical writings on hope, referred to above. Building on this seminal work, sociologists and anthropologists have explored the mechanisms by which hope is generated and sustained, and shape actions.

A valuable contribution in this regard is that of anthropologist Ghassan Hage, who conceives societies as “mechanisms for the production and distribution of hope”.

Focusing on events in the early 2000s, and the defensive, exclusionary practices that he saw as then emergent in Australia, he noted that:

“The kind of affective attachment (worrying and caring) that a society creates among its citizens is intimately connected to its capacity to distribute hope.”

The events Hage referred to included overt expressions of racism and the rise of One Nation, the Tampa (“children overboard”) episode, and the xenophobia whipped up and exploited by politicians of various persuasions, but particularly those in the then governing Liberal Howard government.

Much of what Hage noted 20 years ago pertains now, but some trends have intensified, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

Throughout the pandemic, hope has strongly attached to science and technology, especially to vaccines, which promise to deliver freedom from disease and death, and enable people to resume some sense of normality in their lives.

Much is at stake in the fulfilment of this hope, especially for the legitimacy and standing of the various authorities and experts who have promoted science-based measures.

While many look to science for answers, it alone cannot provide them. In fact, science has been found wanting in many respects and subject to contestation.

A major lesson of the pandemic thus far is the widespread failure of risk governance, and the questioning of its underpinning science-based claims.

Risk, by definition, is calculable and thus governable – and technology is seen as key in governing risk, as can be seen in the reliance on epidemiological modelling, testing, QR codes, masks, and vaccines. With this focus on science and technology, it’s important to keep in mind Hage’s important observation on the social distribution of hope.

Read more: Fact-checking the fact-checkers: Platforms are failing the misinformation test

Groups do not necessarily share the same hopes or subscribe to the same means to fulfil them. Risk and technologies don’t figure in all citizens’ conceptions of hope. For sure, some people’s hopes attach to the scenarios provided by epidemiological models that are, in the event, based on incomplete and potentially faulty information – and like all models include assumptions and biases that benefit some groups and disadvantage others.

Others pin their hopes on non-science-based information obtained online or from other sources, which may seem persuasive but be unreliable.

Both state and non-state actors have used the opportunity provided by the pandemic to distribute “misinformation” and rumours via social media for their own reasons – the so-called infodemic. And some people evidently ignore these sources, and instead attach their hopes to more short-term goals, such as how to survive the next day.

COVID driving inequality

The pandemic has quickly laid bare and reinforced all kinds of inequality, with some companies and groups benefiting massively from the acceleration of digitalisation and lockdowns, and others being left behind.

A housing boom, fuelled by low interest rates and increased savings among some groups, is dramatically widening inequalities in access to shelter with those cashed-up “trading up” or buying second or third properties, while others struggle to get a foot on the housing ladder. Evidence points to growing housing insecurity during the pandemic.

What societies need now more than ever are narratives of hope that transcend narrow group or sectional interests, and provide groups who are excluded and marginalised from society – such as those who have lost their jobs and businesses, or are in precarious employment and/or housing, or suffer discrimination on the basis of their age, gender, sexuality, or other criteria – to gain a sense of inclusion and purpose, and foresee a meaningful future.

This is far from a return to “business as usual” that many long for since, patently, the pre-pandemic status quo has benefited a relatively small minority of the population to the detriment of the majority.

Currently, many hopes are attached to the short-to-medium-term future – for survival, security and safety – rather than to fundamental social change. But when does this latter hopeful discourse start, if not now during this so-called “unprecedented crisis”?

As sociologist Sylvia Walby argues, with reference to the 2008-09 global financial crisis, crises can provide the catalyst for renewal, for creating alternative futures.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a “hopeful moment” – to use a phrase coined by Hirokazu Myazaki – to create opportunities for envisioning alternative futures, ones that are more inclusive and caring, less environmentally destructive, and oriented to fulfilling basic human needs.