Australia’s vaccine rollout has been the topic of much criticism. Having one of the lowest coverages among high socio-economic countries, many have been asking when the marathon will end – although it’s “not a race”.

Read more A matter of perspective: How to improve the vaccination uptake

Today, the Commonwealth government unveiled the technical advice that has informed the national plan to return to normal and learn to live with the virus.

The modelling was led by the Doherty Institute, and involved the University of Melbourne, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Monash University, Curtin University, Telethon Kids Institute, and the University of New South Wales.

The role of vaccination in the population

Australia’s vaccination plan to date has relied on protecting those most at risk of catching COVID-19, and those most likely to develop serious illness.

This translates to frontline workers (including healthcare and quarantine staff) and, primarily, the elderly. A very limited vaccine supply issue was further complicated by ATAGI recommendations that AstraZeneca was preferred only for those aged over 60, due to the risk of blood clots.

Read more COVID vaccinations: One shot, two shot, mixed or not?

The point of this immunisation strategy is to try to make sure that if there’s an uncontrolled outbreak, our health system won’t be overloaded, and the number of deaths will be minimised.

This makes sense, especially when vaccine supplies are limited, and the only vaccine we have plenty of is restricted to those over 60 anyway.

However, now that a sizeable percentage of that population group has had at least one dose of vaccine, should we continue moving down the age brackets, or change tack and instead look at those more likely to spread the virus?

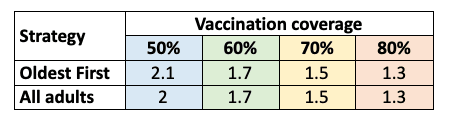

The advice suggests the latter. No matter how much of the population is eligible for an AstraZeneca vaccine, moving to the “all adults” allocation strategy slightly reduces transmission potential at lower levels of coverage, and this can translate to big savings in total cases and health services burden.

Of course, transmission potential is only part of the story. There are many diseases that have a transmission potential (and Reff) well above 1, but if the number of people who get seriously ill is very small, does that really matter?

Read more Reffing hell: Restrictions reign, but it’s a rocky road to zero COVID

To investigate this, the consortium used a dynamic model of disease and clinical outcomes.

Dynamic transmission models are required

An agent-based model was developed, which explicitly models everyone separately, including their vaccination time and type, whether they’re infected with COVID-19, and when they enter/exit isolation.

This model, covering all Australians (25 million), is then fed into a model of clinical pathways, which includes emergency departments, hospital wards, intensive care, and mortality. This framework allows for investigation of the trade-off between disease severity and disease spread.

The modelling assumes that once some level of vaccine coverage is reached, infection enters the community, and no lockdowns or measures other than quarantine and isolation occur.

Under the government’s proposed 70% coverage levels, the modelling suggests a peak ICU load of just over 1000 individuals, comfortably within national capacity levels, and occurring six months into the future – a very long time for a model to project.

Transmission-reducing strategy looks to be the way to go

Interestingly, the strategy targeting key transmitters results in less clinical impact (including deaths) than a strategy targeting those most at risk, effectively cocooning those who are at risk from becoming infected.

Despite seeing more cases, the transmission-reducing strategy results in fewer hospitalisations, and fewer deaths.

This highlights the change in strategy – moving from those most at risk to those most likely to spread. It looks as though Australia may have already crossed that threshold.

Children are not a priority group with limited supply

Speaking of transmission reduction, there’s been much public discourse on whether children should be vaccinated, and what impact they have on COVID transmission.

The United Kingdom’s Joint Committee of Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) has advised that vaccination should not be routinely offered to those aged 12 to 16 years, unless they are at increased risk of severe outcomes.

Despite strong criticism, the current evidence base suggests children aren’t key transmitters of COVID. In a world where vaccine supply is severely limited, the modelling shows that children aren’t a priority group, either for reducing transmission or managing clinical impacts.

Modelling is not a prediction

It’s important to realise these models are synthetic, and aren’t predictions. There are many assumptions underlying the work that can – and likely will – change, and so modelling can only provide an indication of what may happen next.

For example, the modelling has assumed that once vaccination reaches 80% of the population, no more occurs.

Clearly, this isn’t what would happen. However, although the specific numbers associated may change, the high-level messages will likely remain the same.

Where is the future headed?

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has referred to the “plan to live with the virus”. The modelling advice extends six months into the future – projections beyond that point would be so uncertain that we might as well flip a very large coin.

There’s been no timeline commitment for when Australia will reach its first key threshold – 70% of the eligible population fully vaccinated – but it’s important that the sooner that threshold can be reached, the better.

For the near term, the short and sharp lockdowns we’ve all become familiar with will continue. As vaccine supply increases, and we drive the transmission potential closer to one (hopefully by year’s end), then slowly the need for these lockdowns will reduce.

When this happens, at some point, cases will rise. What we hope is that they won’t result in large numbers of unmanageable hospitalisations and deaths.

Then, slowly, we can return back to our pre-pandemic lives.