In February, Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese told Parliament that an Australian government had yet to acknowledge the nation’s true history. The section about the nationwide killing of Indigenous people by European invaders was usually missing.

“We have all failed,” Albanese said. “Truth must fill the holes of our national memory.”

The Aboriginal people who died at the hands of the settlers should be recognised, he said. “They, too, died for their loved ones. They, too, died for their Country. We must remember them, just as we remember those who fought more recent conflicts.”

Albanese also confirmed his support for the Makarrata Commission, part of the Uluru Statement of the Heart, released in May 2017 by the First Nations National Constitutional Convention.

A Makarrata Commission would tell the truth about how Australia was colonised, including the massacres of Indigenous people that took place all over the continent.

A month after Albanese’s speech, the Victorian government announced it would hold the nation’s first truth and justice commission – to tell a more complete story of the state’s colonisation, as part of its historic treaty process.

Monash Indigenous studies historian Professor Lynette Russell AM welcomed Albanese’s statement and the Victorian initiative.

“The myth of the peaceful settlement of Australia is something we need to undo, because we talk about reconciliation in Australia, but for the most part, we like to do it without truth,” she says.

“The War Memorial represents wars between nation states, and essentially wars between equals. In lots of ways, the frontier wars are anything but a war between equals.”

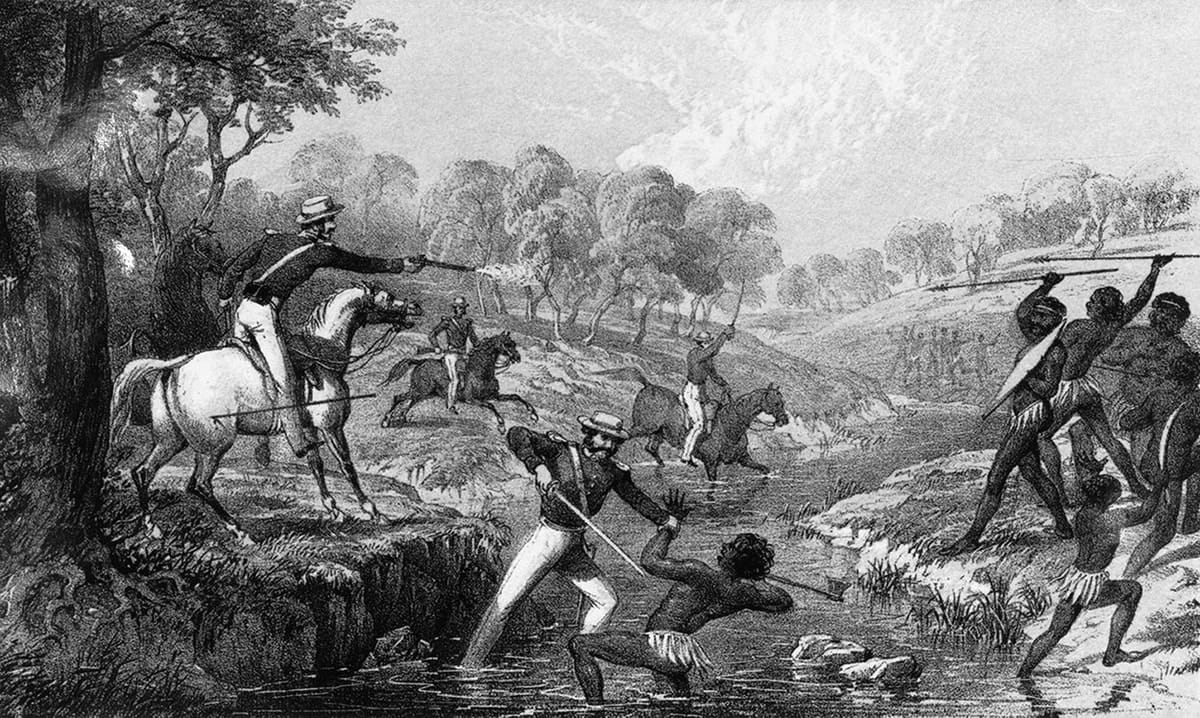

Australian history classes rarely include accounts of a violent frontier, and few monuments exist that tell the story of the Indigenous people who lost their lives in a conflict sometimes called “the frontier wars”.

Although work is being done to uncover the stories of Aboriginal resistance and to document Indigenous massacres, these accounts haven’t yet entered mainstream understanding, or bipartisan acceptance.

“We need to improve the historical literacy of Australians,” Professor Russell says. “It was not a mythic, peaceful settlement. It was an invasion. It had deep ramifications for Aboriginal people, their ongoing dispossession and alienation. If we want to undo some of that, or we want to move forward as a sophisticated, reconciled nation, then we’ve got some growing up to do.”

Some historians, including Henry Reynolds, have called for the story of the frontier wars to be incorporated into the Australian War Memorial. But Professor Russell isn’t sure the memorial is the best place to tell the story.

“I think it’s a really great debate, and it’s one a mature nation could have, and it could be really fruitful,” she says. “But it has to be done against the background of what, I think, is an obscene amount of money [$500 million] being spent on the War Memorial.”

Reynolds’ research estimated that up to 3000 Europeans and at least 20,000 Aboriginal Australians lost their lives in the frontier conflicts.

More recently, Raymond Evans, of the University of Queensland, has estimated that in this “largely unpublicised guerrilla war”, 66,680 Indigenous people lost their lives in 6000 attacks by settlers and native police in Queensland alone. Queensland was the most densely populated part of Australia pre-settlement, and the “epicentre of the struggle”, he says.

Read more: Australia’s history is complex and confronting, and needs to be known, and owned, now

He and colleague Robert Orsted Jensen arrived at this figure using methodology described here. If their estimate is correct, it would mean that the number of people who lost their lives in Queensland was more than the number of Australians who died in WWI (62,300). Evans puts the ratio of Aboriginal to settler deaths at 44:1.

“The War Memorial represents wars between nation states, and essentially wars between equals,” Professor Russell says. “In lots of ways, the frontier wars are anything but a war between equals.”

The one-sidedness of the conflict has been painstakingly recorded by historians at the University of Newcastle, led by Lyndall Ryan, who have made a map and searchable archive, Colonial Frontier Massacres of Australia, 1788 to 1930.

This research, which continues to expand, estimates 8391 Indigenous lives were lost in the massacres it has been able to verify, and 312 Europeans. Their sources included parliamentary papers, private journals and letters, newspaper articles, anthropological reports and Indigenous records – both oral and visual.

According to the archive, massacres were often planned events that took place in secret without witnesses. A code of silence in the immediate aftermath makes detection difficult – although survivors sometimes spoke out years later, when they believed the danger had passed.

“Should we redefine what we’re talking about, when we talk about the colonial period, as a period of war?” Professor Russell asks.

“Maybe it’s a different type of war, an undeclared war. People see their lands invaded. They see people come, stay, and take from them. Dispossession and dislocation – all follow on from that. Then it segues into the removal of children … then you remove culture and language.

“In a way, it almost dignifies them to put them in the War Memorial as though, somehow, this is equal to attempting to land on the beaches at Gallipoli.”

Not a war in the Western sense

Although Indigenous people sometimes protected their borders, had rivalries with other tribes, or conducted raiding parties, they didn’t wage war in the Western sense. “They were doing something different,” Professor Russell says.

“People often say, ‘The Maori people fought back, and Aboriginal people didn’t.’ That’s absolutely not true. We know Aboriginal people fought back.

“[But] If you read, particularly, some of the work on the frontier wars, you do start to get this idea of Aboriginal people creating skirmishes, plotting, and planning in the ways we expect Western war to proceed. They are battle-ready, and they’re working out the best strategies for this.

“Now, they might have been doing that, but my fear is, because you’ve already got in your mind the view of the noble soldier, you then ascribe that to Aboriginal people, who are retaliating against the invasion in their land on their terms, not the European terms. That makes it really quite tricky to then turn around and say, ‘Oh, look, it’s war as we recognise it.’”

During the Eumeralla Wars – a protracted conflict between the Gunditjmara people in what’s now known as Victoria’s Western District, British colonists and police, the Aboriginal resistance was regularly reported in the press, Professor Russell says.

Indigenous people “fought back in various ways. They fought back overtly. They actually, literally, attacked settlers’ huts. Particularly, if you’re a shepherd on the outskirts of a station, then you could be in a lot of trouble, but they had to be very careful in how they managed their retaliation …

“There’s also covert retaliation – retaliation that the settlers might not have even seen, including the use of sorcery and magic, to influence people.”

The siege mentality

In the mid-19th century, colonists recognised that “they were under siege”, she says. “It was commonly spoken of. It was also common for settlers to talk about the validity of Aboriginal people trying to protect the land … Trying to chase off the invaders. It was part of the general writing. People wrote it in their diaries. They wrote it in letters to the newspaper. They would say things like, ‘Who can blame them. We’ve taken this from them.’”

But by the turn of the century, this conversation about Aboriginal resistance all but vanished from public view, she says.

“I think it’s tied into the dying-race paradigm, where, suddenly, everybody thinks Aboriginal people are dying out. It smooths the pillow of the dying race … humanitarianism comes to the forefront.

“Aboriginal people are needing protection. They’re needing to be looked after, but there’s also an anticipation they will go away – as in, they’ll disappear. They will be absorbed into the wider population. They’ll become white, or they’ll die out.”

In reality, Indigenous people were herded onto protectorates, deprived of their liberty, punished for talking in their own language, and their children were taken away. “It’s out of sight, out of mind,” Professor Russell says.

She hopes that during the Victorian truth and justice commission “these stories of dispossession, and violence, and all the rest, can be captured, kept, and held in posterity. People in the future will know what happened here. To me, that's the most important thing we really need.”