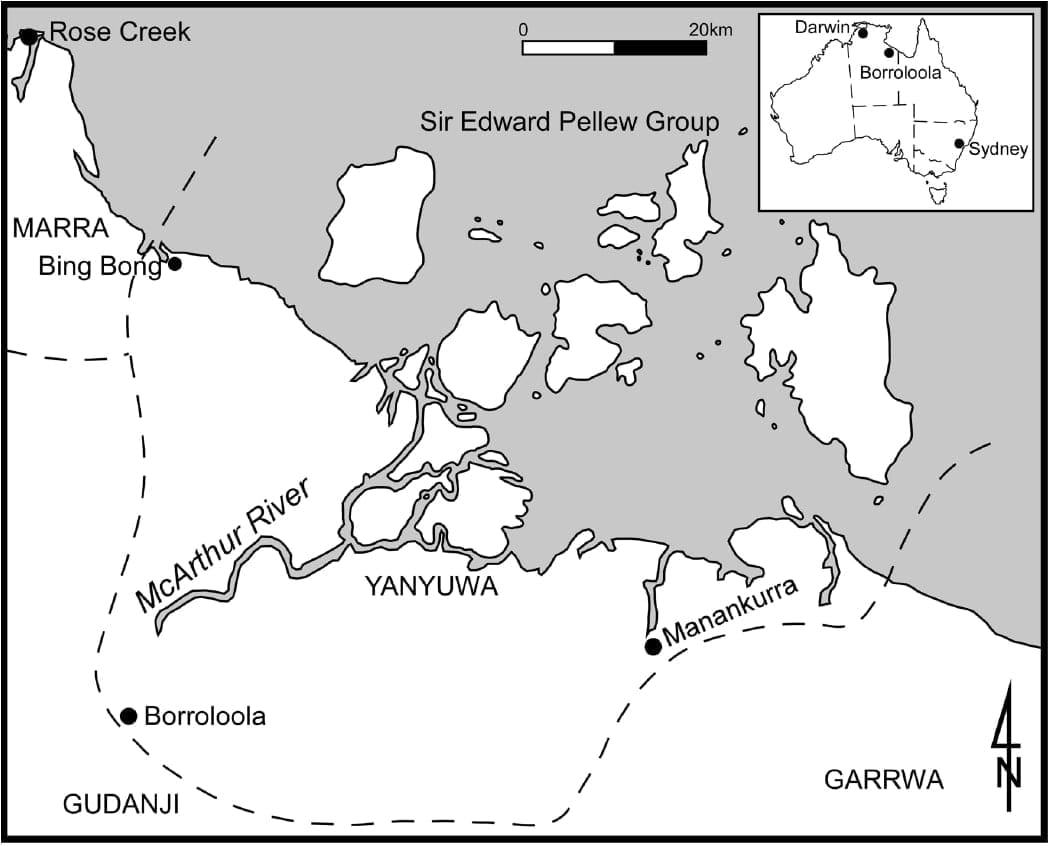

In Borroloola, a small town near the Gulf of Carpentaria, memories and stories of flu pandemics from 50 and 100 years ago have influenced the local Yanyuwa people’s response to COVID-19.

“Many people, and certainly politicians, imagine remote Aboriginal communities as sites of vulnerability; isolated places of little hope,” writes John Bradley in an essay, Telling a Yanyuwa Story of the Pandemic, co-written with Flinders University anthropologist Amanda Kearney.

“This is not the case. Yanyuwa stories of the COVID-19 pandemic show that people have pulled through the most challenging phase of this pandemic with their families and community intact.”

From 24 March, a strict lockdown was enforced in remote Northern Territory communities – people could travel freely within their ancestral land, but weren't allowed to leave it except on urgent medical grounds (the restrictions lifted on 5 June).

In addition, the Yanyuwa took the extra measure of limiting the amount of alcohol people could buy, to six cans each. To promote good health, many also travelled “in extended family groups to parts of country for which they have clan ties”, including the Pellew Islands in the Gulf.

“This is a far more culturally-nuanced response than staying locked down in the camp back in town, where living arrangements are often cramped, and boredom can rapidly set in,” Bradley and Kearney write.

Dr Bradley has spent 40 years living with the Yanyuwa in Borroloola – a town of about 870 people.

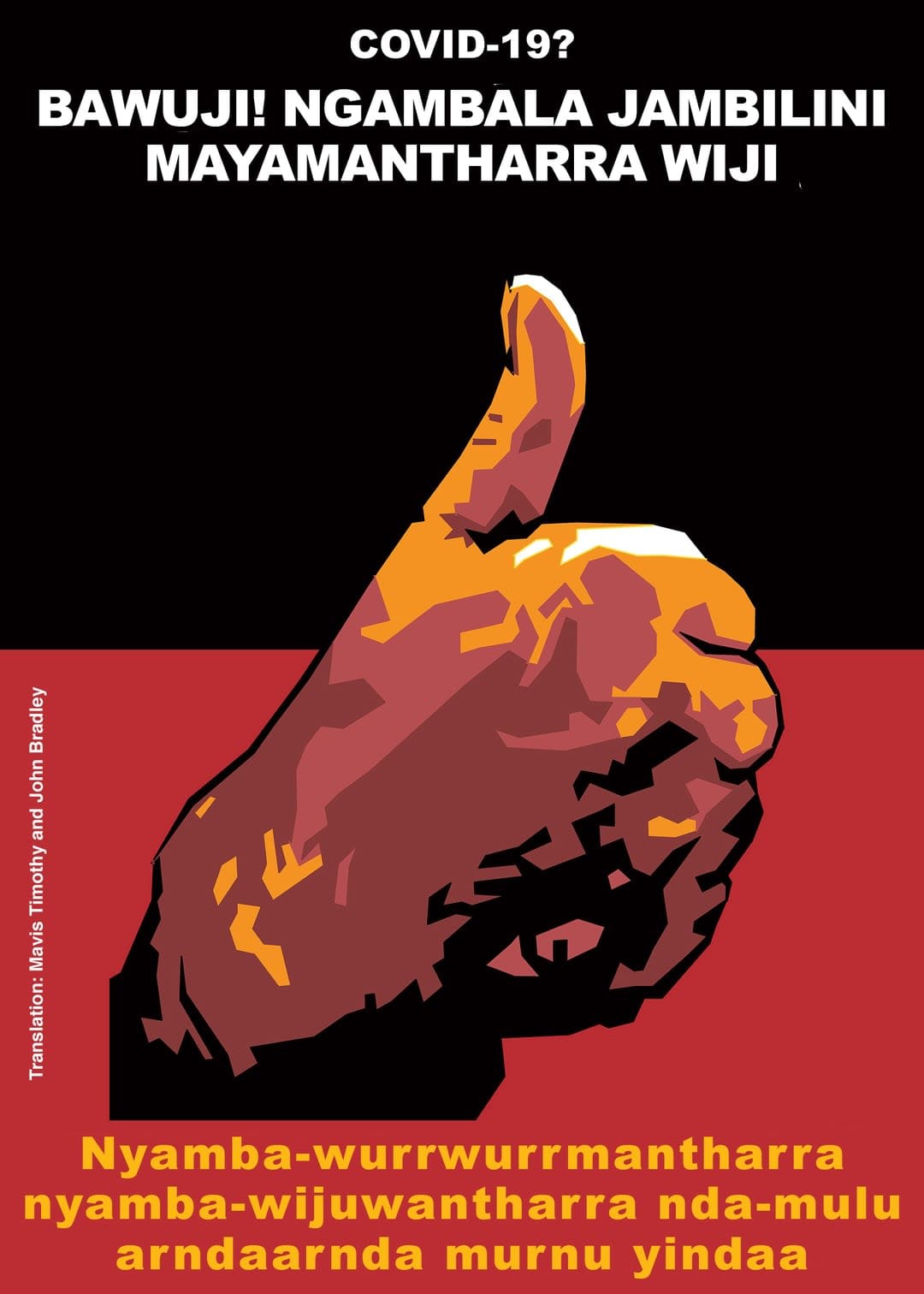

Since COVID-19 reached Australia, he and Dr Kearney have been in regular telephone and Zoom contact with the community, sharing experiences of the lockdown. Dr Bradley has also collaborated on posters in the Yanyuwa language. They advise: “If you are coughing, cover your mouth with your elbow”; “Don’t shake hands and don’t hug”; and “Go back home to Country, look after family”.

Family has been central to the Yanyuwa’s pandemic response, Bradley and Kearney write:

“The presence of extended kin has mitigated against loneliness during lockdown, family has been the cohort to travel out bush with. Those going out bush were able then to bring back bush food for those who had to remain in town as part of sharing and looking after those with less mobility and resources.

“And caring for elder family members has been the dominant theme in discussions of why social distancing and isolation have been so vital at this time, from the need to designate special shopping hours for the elders, and the need to stay away from the old people’s home.”

Read more: Fears over the impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Australians

The memory of elders dying of the Hong Kong flu in 1969 has kept the Yanyuwa vigilant, Bradley and Kearney write. The Hong Kong flu, which is estimated to have killed about one million people around the world, came to Borroloola via two Yanyuwa who travelled from Darwin for the 1969 August rodeo.

After the first eight deaths, the Yanyuwa camp on the east side of the McArthur River at Malarndarri was abandoned, with families setting up camps on the western side.

Maria Pyro, the deputy principal of the Borroloola High School, told an Alice Springs radio station that she was a baby when the flu spread, and learned what happened from her parents and grandparents.

“A lot of people died at that time,” she said, “I think it was maybe 50 or 60 people, mainly old people ... and that was very, very sad. We lost a lot of people with cultural knowledge and history, and we don’t want that to come again.”

Read more: What we can learn from Indigenous Australians about living in harmony with the country

Senior Yanyuwa woman Dinah Norman a-Marngawi was 30 when the Hong Kong flu hit the community. She told the researchers:

"We have been really careful this time. We follow the rules, we don’t want to die, we are helping each other. Maybe if we had of known these rules when that Hong Kong flu came, people would have stayed alive."

Dr Bradley says the Yanyuwa are following the local and international COVID-19 news with interest and attention. They're aware of the controversial theory that the virus escaped a lab in Wuhan, China, for instance, and that the elderly and the poor are the most vulnerable to infection.

The collective view is that COVID-19 is a “whitefella virus brought to Australia by tourists returning from overseas, spread by travellers, and the product of Western science”.

At the same time, the Yanyuwa have their own beliefs about why the Hong Kong flu and the Spanish flu of 1918 – the first pandemic to arrive in Borroloola – was so devastating to their people.

These pandemics “were attributed to sorcery and the desecration of particular sacred sites”, Bradley and Kearney write. Ngangkarrdila and Wurrwurr, two sites north of Borroloola, are Flu Dreaming places, powerful and dangerous to visit, the Yanyuwa say.

Some Yanyuwa connect the arrival of Spanish flu to Borroloola with the arrival of the Australian writer William Edward Harney, a returned Word War I soldier who had served in France. Sorcery was enacted at a Flu Dreaming site at this time, some say; others that cattle broke branches from an ironwood tree, desecrating the site.

Bradley and Kearney write: “Yanyuwa old people recalled Harney’s presence in Borroloola at the time of the sickness, and Harney himself is said to have come back from the Great War in 1919 a broken man, shattered by what he had witnessed.

“He recalled many years later, ‘I’d never crack on that I'd been to the war. I was somehow or another ashamed of the war … I rode 800 miles to Borroloola on a horse to forget about it.’”

"What a longer-term focus on Yanyuwa responses to pandemics reveals is that Aboriginal people undertake culturally-responsive health strategies that more often involve country and kin."

The Aboriginal men who brought the Hong Kong flu to the Borroloola rodeo were also believed to have used sorcery.

The Yanyuwa, in common with other Indigenous societies, place emphasis on seeking to understand why pandemics have occurred, Bradley and Kearney write.

Sorcery and the desecration of sacred sites do not fit Western understandings, but speak to Yanyuwa beliefs that the country itself is powerful, and the relationships within it need to be tended in the correct way.

In responding to COVID-19, the “Yanyuwa have undergone a process of determining where sickness came from and how it might be resisted”, they write – just as they did with the Hong Kong and Spanish flus.

“What a longer-term focus on Yanyuwa responses to pandemics reveals is that Aboriginal people undertake culturally-responsive health strategies that more often involve country and kin.”

Through publishing this paper, Dr Bradley hopes a wider audience can appreciate the adaptability, responsiveness and agency displayed by Indigenous people.

Telling a Yanyuwa Story of the Pandemic, authored by Yanyuwa Aboriginal Families, Professor Amanda Kearney from Flinders University, and Associate Professor John Bradley, Deputy Director of the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, is in press with the Oceania Journal of Anthropology.