Before delving into my topic, I must disclose a conflict of interest: I'm a performing artist, and have been since I left school in 1975. The excitement, discipline and inherent vulnerabilities of performance have represented the foundations of my various careers throughout the subsequent 40-plus years, and I can attribute most of what I would regard as a personal philosophy to the many wonderful colleagues with whom I've shared the world’s stages.

So, in talking about the importance of performing arts, and the need to avail our diverse communities of those arts, whether as performers/workers or as patrons, I will be naturally lacking in objectivity.

As my childhood grew into teenage-hood, I never seriously considered a career outside of music; this despite growing up in Glen Waverley, which during my first two decades was partially undeveloped orchard land on the southeastern fringe of Melbourne – the epitome of a new suburb.

I was so drawn to performance as an end in itself that I dropped out of Melbourne University Conservatorium of Music to pursue the least-secure of career paths: jazz pianist and composer.

I won’t dwell on this, save to say that it all turned out rather well; a few years in Europe and the States, followed by a return to Australia armed with a fresh perspective, new ideas and brash (if not always warranted) confidence.

Jazz music – based largely on improvisation – taught me to think on my feet, practise hard, and listen closely. It’s a collective discipline largely, one in which you're raised by those around you, who you simultaneously also serve – not a bad metaphor for life. There's also a similarly symbiotic relationship with the audience, to which energy is transferred, and returned in a virtuous circle.

So, why are performing arts important? Indeed, why should we invest in new infrastructure dedicated to them in our fast-growing cities when there are so many other important pressures on organisational and government budgets?

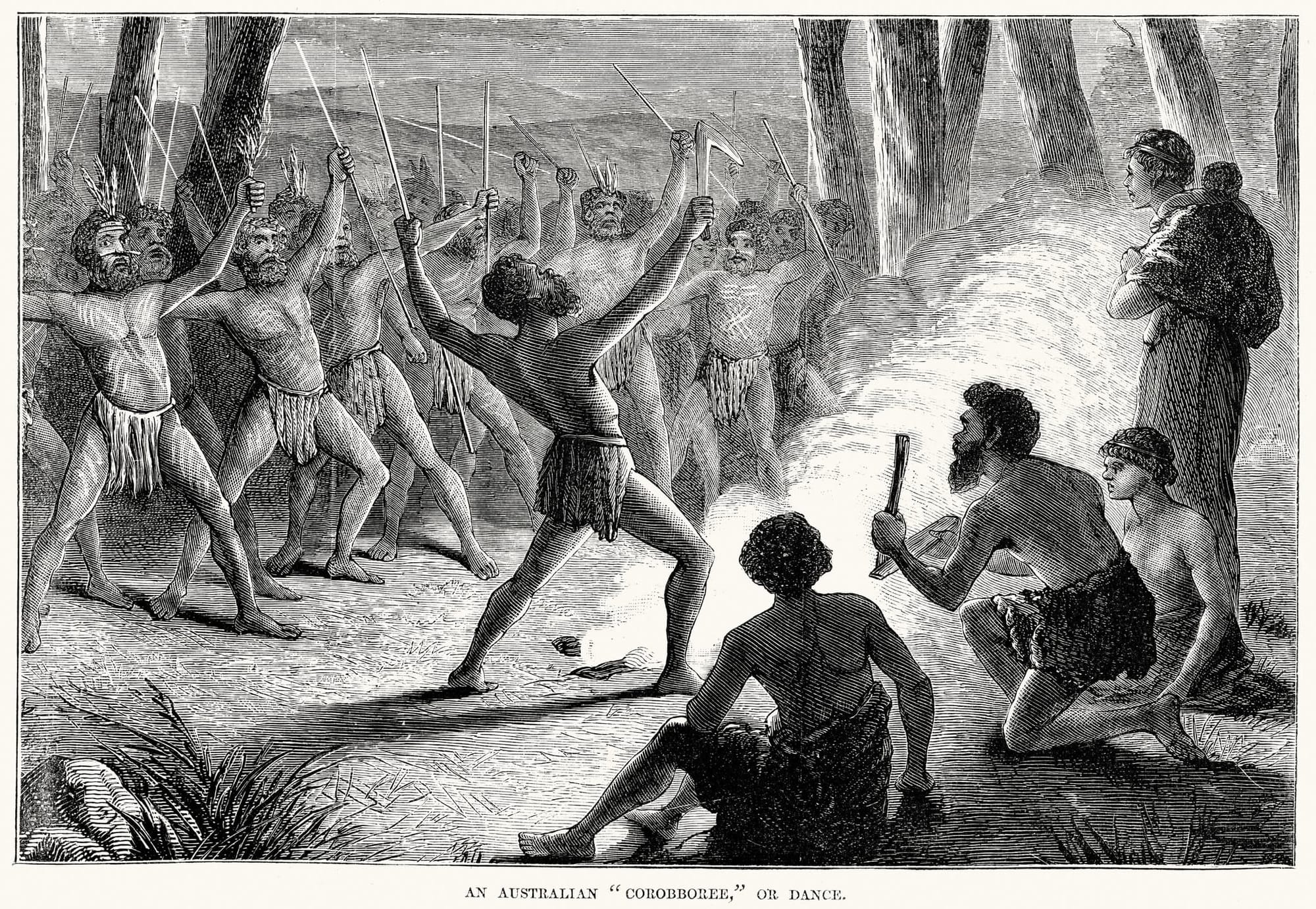

Firstly, let’s remind ourselves of who and where we are. Australia has been inhabited for possibly 80,000 years, and our First Nations are still the living practitioners of the world’s oldest continuing performative traditions. The ceremonial rites that combine in single acts of expression music, painting on body and ground, dance and storytelling are profound celebrations of identity and place that break from linear, causal time, opening a space in which a vertical concept of time brings together past, present and future into one series of instants. Those engaged in quantum physics and speculative cosmology will be familiar with this notion.

With these traditions providing such an extraordinary foundation, we should be able to see the cultural and nation-building aspect of performance as of singular importance to our identity as Australians.

Our introduction to performance starts in infancy, with play. As children, we create imaginary worlds in and out of which we can move at will. This is where we take on other personae, learn to use our bodies as instruments of creation, draw, make, sing, dance and act.

The word ‘play’ has allowed the inner child to live on in the constant wonder that still underpins our professional lives as artists, and our experiences as audience members.

We play music, see a play, make a play on words. Of course, it lives on in sport, too, where the idea of play still links our collective early childhood experiences, and as a sports-mad nation the parallels to the performing arts ought to be obvious.

Many cities include a cultural precinct containing a critical mass of infrastructure and access linking visual art to performance. Melbourne is particularly well-endowed in this respect, with plans well-advanced for new galleries, educational facilities and flying walkways designed to draw together artists and patrons in an exciting creative hub.

That the city may have grown beyond the expectations of the planners of the '50s and '60s is to some extent belied by the fact that, whereas Monash University’s original Clayton campus was once surrounded by quasi-farmland, it's now considered to sit at the geographical centre of Melbourne.

Fast-growing communities, in many cases containing large proportions of recent arrivals, are taking the cultural histories of Melbourne to a new synthesis, one in which the old geographical centre, the original seat of power and influence, now sits in relation to (rather than over and above) the greater metropolis.

As these communities develop their own narratives around the idea of ‘Melbourne’, particularly the suburbs in which they live, cultural hubs of various kinds will reflect that new process of belonging.

Performance represents a locus of freedom and discipline, where plurality is expressed through the encouraging of forms and outcomes that give voice to the emerging sense of what it means to belong.

As our First Nations have taught us, performance and belonging are indivisible, the one an expression of the other, unbounded by time and space, but very much about identity and place.

Across the nation, Australian suburbs are developing high-level cultural hubs, including performing arts centres, which ensure the opportunity to connect with communities and allow strategies towards social cohesion through performance to grow.

The opening in May of the Ian Potter Centre for Performing Arts at Monash University’s Clayton campus literally builds on a tradition established in the Alexander Theatre (1968) of professional and community embrace of a theatre as a place for celebration through theatre.

The new centre seeks to extend into the next 50 years the very principles that defined its initial decades: the sense of the value of the individual, the embrace of the performative moment as one of the defining qualities of human experience.