In early March – as the COVID-19 pandemic began killing infected Australians, borders were about to be shut, social distancing rules were imminent – Monash University’s Dr Peter Slattery shifted his attention from the question of “Can pledges help prevent the virus spreading?” to “How can social science help policymakers understand public behaviour?”

He was involved in Stand Against Corona, a “global coalition of concerned citizens and leaders”, from business and charities, “committed to doing what they can to stop the spread”. Stand Against Corona was – and is – about taking an online pledge to wash hands and cover mouths, stay home, and telephone or video-call the vulnerable. It aimed to lessen community transmission of the deadly virus.

But the virus kept spreading. By mid-March, both actor Tom Hanks and his wife, singer-songwriter Rita Wilson, and the Minister for Home Affairs, Peter Dutton, were diagnosed and isolated in Australia, and Victoria had declared a state of emergency. Dr Slattery, a research fellow at BehaviourWorks Australia, changed the approach.

“I saw that governments were putting out a lot of information, and saw the importance of understanding the different types of messaging they might use, and generating insights that might be useful for guiding that. I also saw the importance of enabling governments to understand how different groups were responding to their messages, and whether they were reacting in different ways. I wondered, what could a social science researcher do to help?”

BehaviourWorks – part of the Monash Sustainable Development Institute – is now leading the Australian chapter of the Survey of COVID-19 Responses to Understand Behaviour (SCRUB) project.

Dr Slattery and Dr Alexander “Zan” Saeri, a psychologist interested in health, technology, and environment, are the lead researchers, alongside Michael Noetel at the Australian Catholic University, and Emily Grundy from Deakin University. In addition to founding the SCRUB project, this team is also involved in the Rapid Effective Action Development Initiative (READI), a global group of researchers collaborating to examine “significant societal issues”.

Tracking behaviours in real time

The SCRUB project is a real-time survey tracking how groups of people all over the world are behaving. It’s designed to help government policymakers by documenting how relevant public experiences and behaviours are changing over time. It involves more than 120 international collaborators.

The questions used in each new “wave” of the survey are updated based on the feedback of policymakers and changes in the pandemic situation. The Australian team is funded by the Victorian government, which uses the insights to inform policy.

The results are released via a publicly-accessible interactive dashboard, and all data is publicly available for other policymakers and researchers to use. Some of the findings from past waves are summarised here.

The uniqueness of the SCRUB project comes from the fact that the questions are constantly being updated, the data is open, and the results are rapidly shared in an interactive online dashboard.

“No-one else is using a dashboard like us,” Dr Slattery says. “We have a real-time visualisation of the information we collect, which anyone can access and learn from. We also share all the code and data underneath it. Rather than optimise our work for publications, we’re really trying to focus on the practical impact.

“There’s two ways that we try to add value. In the immediate or short term, we provide governments with useful actionable insights. In the longer term, we can generate useful insights about how different groups responded to the pandemic and were affected over time.”

Read more Follow our blog here for rolling data updates

He says the survey may not necessarily end any time soon. “We’ll keep running the survey until there’s no longer a need for it. It’s very impact-driven – we keep doing it while it’s useful. It’s iterative, so we’re always updating the approach to ensure that the results remain useful.”

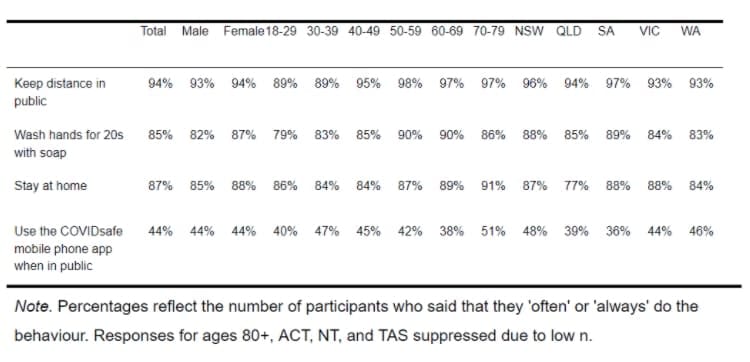

About 5000 people in 40 countries have so far contributed to the survey. The first three waves of results have found Australians were largely adhering to personal protective behaviours; however, they weren’t keen on the COVIDSafe app – more than half (56 per cent) were “sometimes”, “rarely” or “never” using it.

Wave three showed that at the peak of the COVID-19 breakout in March and April, most Australians were adhering to the five key behaviours recommended by the federal government’s Department of Health to stop the spread of the virus. But these rates dropped slightly in May as fewer people were infected and restrictions loosened.

Significant findings in the data

A deep dive into the data is fascinating. As Dr Saeri points out, it’s “of significance” that more than half of respondents are not using the state government’s phone app, which traces people coming into contact with each other.

“The necessity of using the contact tracing app in public should be emphasised in communication from state and federal health authorities,” he says, adding that “our data indicates that these are the most trusted bodies in reducing the harm to Australians from COVID-19”.

Dr Slattery says that young people’s relatively low uptake of the app was “a big surprise”.

Also from the data:

- People from Western Australia were the worst at washing their hands for 20 seconds.

- Young adults, aged 18–29 years, are still performing protective behaviours significantly less often than other groups.

- Women aged between 50 to 60 were amazingly good at keeping their distance from others in public, especially in South Australia.

- In May, nearly half (46 per cent) of respondents who didn’t stay home “often” or “always”, said that a factor in them not staying home was their perception that other people were also not staying at home.

- From 12-17 May, 35 per cent of the respondents who said they didn’t wash their hands “often” or “always”, attributed this to not remembering.

- People over 70 were most likely to use the COVIDsafe app when in public. South Australia had the lowest uptake (36 per cent), while New South Wales (48 per cent) had the highest.

The survey also examines changes in other variables such as wellbeing, anxiety, predictions of infection, and interventions to change behaviour.

Australians’ perceptions of health authorities have remained positive, with national and state authorities remaining highly trusted to minimise the harms of COVID-19. However, confidence in the World Health Organisation (WHO) fell from second most-trusted to least-trusted between waves one and three of the survey.