This week on What Happens Next?, we’re kickstarting a new series on critical minerals. As we transition to a decarbonised future, away from oil and coal, our technology will run on ores such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals.

How will this cause global politics to shift? Can mining and sustainability go hand-in-hand? And how can we ensure a just transition for all?

Watch: A Different Lens: The Business of Energy

In this new episode of Monash University’s podcast, What Happens Next?, our guests discuss the challenges and opportunities critical minerals can play in transitioning society away from fossil fuels to a more sustainable future. Can Australia be a leader in the critical minerals race?

Host Dr Susan Carland is joined this week by Professor Susan Park, Professor of Global Governance at the University of Sydney; Dr Mohan Yellishetty, Associate Professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at Monash University; and Dr Paris Hadfield, Research Fellow at the Monash Sustainable Development Institute.

If you’re enjoying the show, don’t forget to subscribe on your favourite podcast app, and rate or review What Happens Next? to help listeners like yourself discover it.

“We all are familiar with aluminium, iron or copper, lead, zinc. So they have been the mainstream metals, and most critical minerals always were companions, or “hitchhikers”, we call them. And that's where they are part of it, but we never were interested in them... Now we are chasing them back again.”

Dr Mohan Yellishetty

Transcript

[Music]

Dr Susan Carland: Welcome back to What Happens Next?, the podcast that examines some of the biggest challenges facing our world, and ask the experts, what will happen if we don't change? And what can we do to create a better future?

I'm Dr Susan Carland. Keep listening to find out what happens next.

[Music]

Susan Park: So one of the things that we've noticed, and that colleagues and I have been working on, is the fact that Australia really has a third-world economy, even though we have a first-world lifestyle.

Paris Hadfield: I think we need to meet people where they are and listen to their concerns, and have them be involved in defining the pathways forward.

Mohan Yellishetty: Australia, sky is the limit in terms of where we want to position ourselves in critical mineral space.

Anthony Albanese: I support exporting our resources, but where possible, we should be value-adding here, rather than seeing the value add somewhere else, and the jobs created somewhere else.

[Sound of a motor and a car parking]

[Music]

Dr Susan Carland: Even if you weren't already toying with the idea of making your next vehicle an electric one, the skyrocketing cost of petrol lately has many of us considering their merits while staring glumly at the fuel pump.

While we're fantasising, let's imagine that your new electric car only has to be charged once a week, no matter how fast you drive it. Not only that, your impressive imaginary car battery can be charged hundreds of times without failing, was completely clean to produce, and was made right here in Australia.

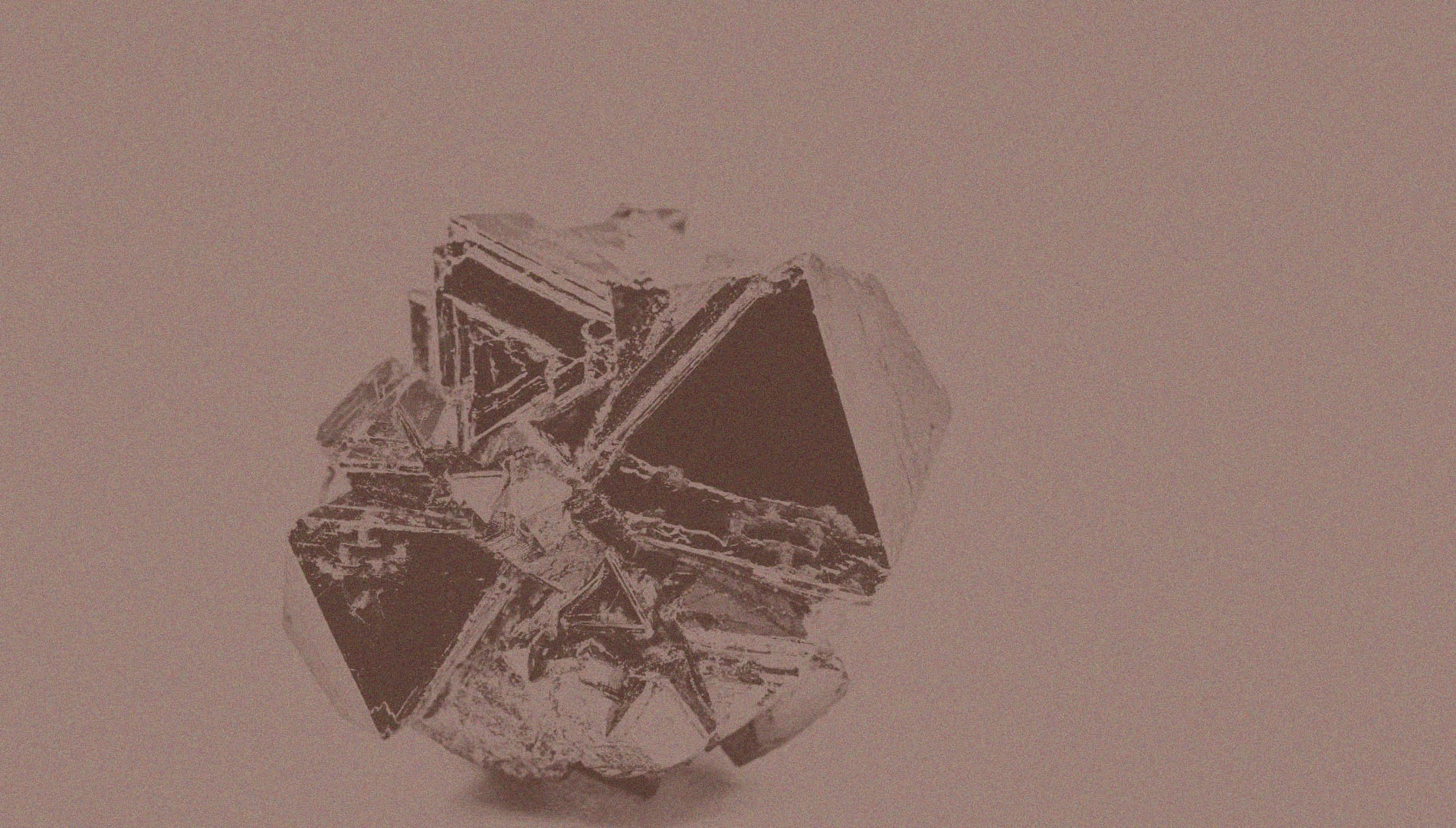

No, it's not the petrol fumes going to your head. Earlier this year, Monash University researchers successfully created just such a battery – one that could be the holy grail of green energy. One of the most vital components of these batteries and most batteries used to store renewable energy, is lithium, a critical mineral which, luckily for us, is so plentiful here in Australia that we supply nearly 60 per cent of the world's reserve.

“Great!”, you're probably thinking. “Where's my new car?” Well, it's not quite that easy.

This week on What Happens Next?, we're kick-starting a new series on critical minerals. As we transition to a decarbonised future away from oil and coal, our technology will run on ore such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth minerals. How will this cause global politics to shift? Can mining and sustainability go hand in hand? And how can we ensure a just transition for all?

Keep listening to find out what happens next.

Susan Park: Hello, my name's Susan Park. I'm a professor of global governance at the University of Sydney, focusing specifically on global governance in the transition to renewable energy.

Dr Susan Carland: Susan! What a great name. Welcome to the podcast.

Susan Park: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here and with another Susan.

Dr Susan Carland: [Laughter] Susan, what do we mean by the term “renewable energy transition”?

Susan Park: It's a big question.

The renewable part of it is transitioning to energy that is not fossil fuel-based, and that can include a whole range of different types of technologies – everywhere from the big and well-known ones, from solar energy and wind technology, through to biofuels and types of processes for capturing carbon. So it's a whole range of different technologies.

But we know the big ones, as wind and solar, obviously needs to be backed by battery storage, lithium-ion battery storage. Because at this point these technologies don't have that capacity so there's a big investment in trying to find ways to store wind when the wind's not blowing, and solar energy when the sun's not shining.

The transition part is the bigger component of that question, which is how we can actually move from an entire society and entire economies that are based on fossil fuels. This is everything that we do is dependent on fossil fuels. How our buildings are structured, what materials they're built from, how we heat our buildings, how we move around our cities, in terms of transport.

Everything that is produced industrially is built on, being driven by, fossil fuel energies. That transition is a massive headache, I guess you could say at this point, because one of the biggest problems in that transition is how you actually get your head around moving whole societies and economies away from this fossil-fuel-dependence.

Dr Susan Carland: I want to ask you to clarify some terms for the average fool, which is me. What are critical minerals and what are rare earth minerals, and are they the same thing, or are they different?

Susan Park: That's a great question. Critical minerals, at this point, are what national governments have identified as necessary for the energy transition. This includes everything from cobalt, copper, rare earth minerals, tin, tungsten, tantalum, all of these that we need to be able to produce solar or PVs, so solar panels, and wind turbines in order for this transition to occur.

The Australian government has a list of critical minerals. The United States government has their list. The European Union has their list. They're pretty similar, but they obviously depend on which technologies these governments have determined that they're going to push forward with as a means to transition their states and their economies.

Rare earth minerals are one of the critical minerals that are necessary, and when I say one of, they are in fact comprised of multiple different minerals that have been lumped under this heading of rare earth minerals. Surprisingly enough, rare earth minerals are not that rare.

[Laughter]

Dr Susan Carland: Okay, first misnomer.

Susan Park: But the reason why they're called that is because they're kind of spread out all over the place, and that makes collecting them and using them and processing them actually quite a challenge.

[Music]

Dr Susan Carland: Dr Mohan Yellishetty is an associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at Monash University. He's recognised as one of the world's leading experts in critical minerals.

So what do we use critical minerals for?

Mohan Yellishetty: Critical minerals, you talk of – when you look around in this particular room itself, you've got computer screens, LCD screens, and you got the LED bulbs. And any technology that you talk of, they underpin by availability of some of these materials.

Even renewable energies, the different technologies, satellite imageries, all of them require very high-precision elements like these critical minerals.

Dr Susan Carland: Okay, so where do we find them?

Mohan Yellishetty: We find them in a range of resources. There are a lot of different ore bodies that host them. But if you look at, for example, my generation of minerals, we all are familiar with aluminium, iron ore, copper, lead, zinc. They have been the mainstream metals, and most critical minerals always were companions, or hitchhikers, we call them.

Dr Susan Carland: Hmm.

Mohan Yellishetty: And that's where they are part of it, but we never were interested in them, and then we discarded them into tailings dams and so on. Now we are chasing them back again. Yeah, so you can find them in every single ore deposit, again, depending on which type of ore body that you're looking at. They could be found in a variety of different ore bodies.

Dr Susan Carland: People originally were just chucking them out and now you're going back to that rubbish pile going, “Where was that tungsten again? Where's the lithium?” [Laughter]

Mohan Yellishetty: Absolutely. Absolutely. That's exactly what happened.

For example, when we did copper mining, cobalt is always associated with copper ore bodies, but their use has not been as much as it is today in the past, maybe two decades ago. And all of that ended up in a lot of these tailings ponds. And they're sitting just for no reason there.

When you talk of critical minerals, we must understand they possess certain specific characteristic features. For example, they are magnetic, they have high luminescence properties, or high thermal conductivity properties, metallurgical properties. They're very unique in the way that they behave, especially when you are aligning with the different other metals.

Let's take for example, gallium, one element which is sourced as a byproduct of aluminium mining, bauxite mining. It's used in LED bulbs. It is used in all these high-tech motherboards and so on and so forth. Yes, we require them because they have to give best performance when they're in operation, so for that reason we need to have them. And not to mention the important property of rare earths, mainly the magnetic property.

Because if you look at wind turbines, let's take that example. There are a number of ways in which the turbine can sort of move. One is through a proper gear system, but that only performs 40 per cent efficiency. But whereas when you have these permanent magnets, which are neodymium, praesidium, and terbium, and neodymium, all these new generation of materials are required to manufacture some of these permanent magnets, which give you very high performance. And then all of them are very, very crucial in those modern technologies.

Dr Susan Carland: Do we have access to many of these things in Australia? Can we mine them here, or do we need to get them from overseas?

Mohan Yellishetty: Yeah, Australia, we are very blessed to have a majority of these critical minerals in our ore bodies. Because Australia is a huge mining country, and mining always contributed close to 10 per cent to our GDP, which meant we mine pretty much every mineral ore that you could think of.

And that means we also have a lot of these companion metals of interest now, which are in huge demand, that the world needs. Yes, we are fortunate that we are able to produce them and supply to the rest of the world.

Dr Susan Carland: Do you think we are going to see Australia and maybe even the world move away from coal, oil, and start focusing on the sort of critical minerals that are used more in renewable sources? Is that the direction we seem to be moving?

Mohan Yellishetty: Yes. Recently we had a roundtable meeting with the Indian Minister for Energy and Renewable Energy Sources. The ambitious plan that India has is they want to add close to 2.5 gigawatts of energy, which is non-fossil-fuel-dependent, per month, which is going to be a huge ask. And that requires a lot of these new generation materials like cobalt, lithium, nickel, graphene, all of… aluminium, copper, all of these ores, they underpin most of these technologies. That means the world needs them, and we have them in our backyard.

[Music]

Dr Susan Carland: Here's Susan Park again.

Susan Park: We do have rare earth minerals in Australia. There are some in the United States, you can find them in all other places.

But the question is how can you actually produce them at capacity to be able to use them effectively in this transition? In actual fact, China has a significant number – in fact, dominates the rare earth minerals – and that's creating a drive by other states, particularly the US, to identify how they can secure enough rare earth minerals and be able to process them for their own transition.

[Music]

Joe Biden: We can't build a future that's made in America if we ourselves are dependent on China for the materials, the power, the products of today and tomorrow.

Dr Susan Carland: All right. I want to ask you a political science question now, which is, as you were talking about where we can find the resources and who seems to have a lot, I couldn't help but wonder if we are going to see a real shift in global powers as we move away from things like oil, and into the importance and influence of having access to things like lithium and other rare materials?

A lot of the… Saudi Arabia and the Gulf has achieved what it has and had the influence that it has because of their access to oil, and the fact that they can sell it. And I wonder if we'll start to see countries like that maybe have less and less global influence, and even greater global influence for the countries that now have the things that everybody wants? And what will that mean? What will that mean in terms of shifting geopolitics?

Susan Park: Yeah, it's a great question and we are seeing that dynamic playing out. It's playing out at two levels.

One is the actual extraction of the raw mineral, and Australia is well-placed. We have a lot of lithium. We are in a good situation, you would say, in terms of this transition to renewable energy.

But the extraction process is only part of the global supply chain. And so, in actual fact, we don't manufacture much here. We're not actually taking that much of an advantage of, say, lithium deposits, by being able to transition that into lithium-ion batteries.

So in actual fact, we are possibly going to see some of the same things that we saw with fossil fuels and other types of natural resources, where you fall into a resource-dependence type of trap, which is where you start to be seen as only the extraction state, and not actually be able to produce anything. And there's that big concern in places like Chile that it's really just the extraction of lithium, and they're not going to be able to actually leap ahead in terms of advanced manufacturing, or being able to dominate the renewable energy industry.

And so you can start to see consolidation in some industries. China absolutely dominates rare earth minerals, 97 per cent of rare earth minerals. China is also now dominating solar panels. This is…. The production of solar panels is coming from China. Where is Australia selling its lithium? We're selling it to China. [Laughter] So the geopolitical dynamics are heating up in terms of who is going to dominate the actual technology itself.

In areas like wind, we are seeing a consolidation of the entire wind turbine industry to just seven companies. And so you're starting to think about the benefits or the potential for different types of technology to provide, say, people talk about energy democracy, the fact that anyone can build a wind turbine. Anyone can jump into the solar panel market. Well, that's actually starting to tighten up really, really fast, through mergers and acquisitions. And this is not just political, but political-economic, in terms of what governments are promoting in terms of backing specific industries dependent on these critical minerals.

[Music]

Dr Susan Carland: Susan, are we heading in the direction of the Gulf War III, but this time, instead of fighting over oil, we could be actually having wars or conflict over rare earth materials?

Susan Park: Look, you can't rule it out. I think one of the issues that we have to bear in mind is that certain states are now poised to automatically see the other with suspicion. That is the United States and China.

Now China is obviously well-placed to transition to renewable energy. The United States is playing catch up in a very, very fast [laughter] manner, particularly under the Biden administration. Look, we've seen trade wars between the two. We've seen China be willing to withhold the export of rare earth minerals to Japan. It is willing to use those types of levers, should it feel the need to.

Combined with flashpoints, we're seeing a sort of rolling discontent playing out in relation to Ukraine, in relation to food stuff. And of course, the global pandemic, that's not gone away. There's still some lingering discontent there.

You can't rule out war, but you could hope that states are willing to be able to cooperate enough and to be able to diversify their own energy systems and sources enough that that's not necessary.

Dr Susan Carland: For a country so rich in critical minerals, Australia is much, much further behind than other countries when it comes to transitioning to them. The reasons are complex and perhaps partially rooted in anxiety.

It seems like something that society seems quite anxious about. Anxious about, they want to do the right thing, but also a fear about, “Well, what does it mean and how do we shift away in a way that means we don't lose anything?”

Susan Park: Yeah, there's again, really good points, and two parts of it.

We do have a great deal of anxiety around it. We've known about the climate crisis for literally decades. Going back to the 1970s, in fact. This is not something new, but obviously it is now impacting on our daily lives.

And the anxiety is around what we should be doing as individuals when, in fact, we know that this is a structural problem, that there needs to be a whole of society change in how we live our lives.

And I don't at this point think that it really is a trade-off in terms of quality of life. We can, in fact, transition to renewable energy and still charge up our phones and our iPads, and have that connectivity that we've come to know and expect.

Dr Susan Carland: Dr Paris Hadfield is a research fellow at the Monash Sustainable Development Institute, studying transitions to a decarbonised future, something we’ll explore further next week. She's seen some of the anxiety Susan just mentioned in Australia's many mining towns.

Do you think there's a big fear in the community that some groups might be left behind or excluded in this process?

Paris Hadfield: Certainly. And I think that comes up a lot when we're talking about coal transitions, certainly.

Dr Susan Carland: Mm.

Paris Hadfield: We still see the federal government not willing to say that we won't invest in new coal-fired power plants, and that's obviously problematic for the environment and climate change, but that's a real concern for people.

I think we need to meet people where they are and listen to their concerns, and have them be involved in defining the pathways forward.

Dr Susan Carland: Here's Susan again.

Susan Park: Australia, again going back to the lithium, we have the lithium, but we don't do manufacturing.

So the last federal election, the now-government suggested that this is something we needed to move into. Well, that's something that other governments are well on top of and have been planning for decades. So we're really behind the eight ball in the sense of trying to then create our own manufacturing base to be able to take advantage of this transition.

It's not to say it can't be done. But obviously there's a real lot of catch-up to be done.The biggest concern is the fact that, again, we've lost advantage in terms of the knowledge and the technology that were coming from our scientists, that then went to China because the Australian government just wasn't interested in solar panels enough to invest. And that's really borne fruit for countries like China, even though the technology was produced in this country.

So in terms of the workforces, again, like in Australia, coal, we have the bifurcated coal industry. We've got coal for domestic electricity consumption and that's transitioning, but we also have a huge coal market for external, for export and for steel making, for example, and that continues to boom, despite the climate emergency.

Dr Susan Carland: Cast your mind 50 years into the future in Australia. Imagine we don't get on top of this issue the way you're talking about, we don't start really trying to invest in the industry of rare earth materials and being able to build things with it. We just keep sending it offshore. What do things look like for Australia, and perhaps the planet?

Susan Park: Great question. [Laughter]

One of the things that we've noticed and that colleagues and I have been working on is the fact that Australia really has a third-world economy, even though we have a first-world lifestyle. We just dig stuff up. We're a lot less diverse than we were three decades ago.

I don't see that actually changing. During the global pandemic, for example, the last federal government decided not to actually extend any support for its third- or fourth-largest market, which was higher education.

We're protecting industries that are really not benefiting the average Australian. For example, when I say that, yes, of course we all benefited from our mining boom, but that money wasn't reinvested, and it wasn't used to diversify our economy. And as a result of which, we are going to be further, and further, and further behind.

How and where we invest in Australian money, it's not going into research and development, so where's it going?

Dr Susan Carland: Is it too late to turn the ship around?

Susan Park: Well [laughter], I would like to think we could do that.

The biggest concern is potentially the fact that a lot of investment does need to come from the federal government. A lot of that investment needs to go into research and development, needs to go into manufacturing, needs to go into the shift that is necessary.

And it is not clear to me that the Australian government has the appetite for the risk that is necessary to get us the payoff that we would like in order for the Australian people to be best-placed to take advantage of the renewable energy race, if you like.

Meanwhile, we continue to be a major polluter, which of course has huge ramifications globally.

Dr Susan Carland: Susan, what a horrifying interview. I've absolutely loved it! Thank you for joining us today.

Susan Park: [Laughter] Thank you very much.

Dr Susan Carland: Australia's poised to be a global leader in the critical minerals race if we can just make it happen. And we must, because the future of the earth is at stake. Next week, we'll discuss how we can do it and how we can ensure that no one is left behind along the way. Thank you for joining us for part one of our look at critical minerals.

Thank you as well to all our guests on today's episode: Dr Paris Hadfield, Dr Mohan Yellishetty and Professor Susan Park. For more information about their work, visit our show notes.

[Music]