Can you imagine waking up one day to find that the antibiotics we once relied on to treat common infections no longer work? That a simple urinary tract infection, a sore throat, or a post-operative wound has become life-threatening — not because of its severity, but because we’ve run out of effective treatments?

This is not a problem for the distant future. It’s already unfolding, quietly but steadily; a silent pandemic is upon us, and unless we act decisively, the consequences will be severe.

Antibiotics, one of the great miracles of modern medicine, have transformed once-deadly infections into manageable conditions and enabled routine surgeries, cancer chemotherapy, and intensive care.

Yet today, this foundation of modern healthcare is under serious threat. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve to resist the effects of medications – is growing faster than many people realise. It’s often called the “silent pandemic” because of how easily it spreads without immediate signs, and we can no longer afford to ignore it.

As a clinical pharmacy lecturer, I regularly supervise students on placement at hospitals. With each visit, I witness troubling trends that reflect the growing threat of AMR.

It’s no longer surprising to see multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (below) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with resistance markers to virtually every agent we test. These aren’t isolated anomalies – they’re signs of an urgent and expanding crisis.

In community pharmacy settings, another trend is equally concerning. Many people continue to request antibiotics for symptoms such as sore throats, mild coughs, or fevers – conditions that are often caused by viruses and do not require antibiotic treatment.

I often hear statements like: “A sore throat? I just need antibiotics.” or “Surely antibiotics will fix this fever.” or “Just give me something strong for this cough.” These requests reflect a widespread misunderstanding about how antibiotics work.

People are not to blame; they’re acting on what they believe is best for their health. Unfortunately, this highlights a gap in public awareness about the difference between bacterial and viral infections, and when antibiotic use is truly necessary.

Globally, the numbers are alarming. A major review commissioned by the UK government projected that, without urgent action, antimicrobial resistance could lead to 10 million deaths every year by 2050 – more than the current global toll of cancer.

Beyond the human cost, the economic impact could be enormous, with losses projected to reach more than US$100 trillion due to lost productivity and increased healthcare spending. These are not just estimates – the latest data already shows that more than 1.2 million deaths each year are directly caused by antibiotic-resistant infections, and the number continues to grow.

Australia, despite its robust health systems, is not immune. In March 2025, the Therapeutic Guidelines (eTG) published a major revision to its antibiotic recommendations – an update driven not by new discoveries, but by resistance patterns observed nationwide.

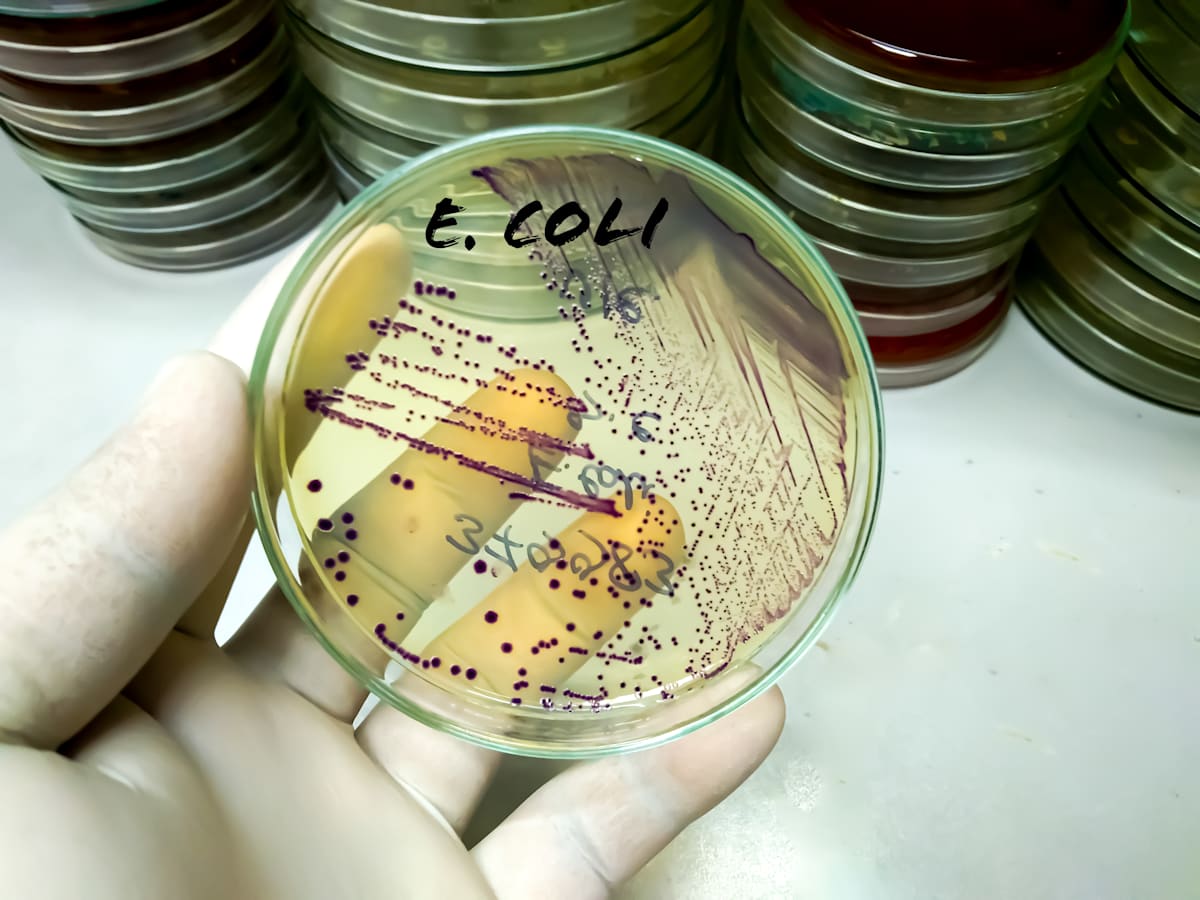

Common pathogens such as Escherichia coli (below), which once responded reliably to first-line therapies, now frequently exhibit resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics.

Prescribers are increasingly being forced to resort to broader-spectrum agents or combination therapies – solutions that are not only more expensive, but also more prone to driving further resistance.

What makes the situation even more challenging is the time and cost required to develop new antibiotics. Producing a single new antibiotic can take more than 10 years and cost more than a billion dollars. Meanwhile, bacteria are constantly evolving, sometimes gaining resistance within just months. We’re racing against time, and right now, resistant bacteria are ahead.

Still, there is hope

Pharmacists are at the heart of the solution. One of the most effective strategies to combat AMR is antimicrobial stewardship (AMS), which ensures antibiotics are used only when truly necessary, in the right dose, and for the right duration.

In hospitals, clinical pharmacists are key members of AMS teams, reviewing antibiotic prescriptions, guiding prescribers, and ensuring responsible use. In community settings, pharmacists play a vital role in educating the public, answering questions, and helping patients understand when antibiotics are not the answer.

The World Health Organisation’s Global Action Plan on AMR has made it clear – health professionals, particularly those who prescribe and dispense antibiotics, have a critical role to play.

To be successful, stewardship efforts must be supported at every level – from hospital policies to national health regulations. Governments must also strengthen infection prevention programs, and invest in the research and development of new treatments. But equally important is the role of individuals – patients, families, and communities all have a responsibility to use antibiotics wisely.

We’re not yet at the point where everyday infections are untreatable – but we are getting closer. Without urgent action, we risk entering an era where the medical procedures we take for granted – childbirth, surgeries, chemotherapy – become too dangerous to perform safely.

Antibiotic resistance is not just a medical issue. It’s a global challenge that affects us all. It will take collaboration, education, and action from healthcare providers, policymakers, and the public to change the course we’re on.