At age 35, one in four Australian women and one in three men were hoping to have a child or more children in the future. But by age 49, about half report they haven’t yet had the number of children they hoped for.

That’s according to the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) 2021 report, released recently. For more than 20 years, HILDA has tracked more than 17,500 people in 9500 households.

While some of the 49-year-old men may still father a child later in life, women at that age are unlikely to have children.

In Australia and other high-income countries, there’s been a long-term downward trend in the fertility rate – the average number of births per woman. In 2019, Australia hit a record-low of 1.66 babies per woman.

Read more: Australians want more children than they have, so are we in the midst of a demographic crisis?

Low fertility rates are partly a result of more people not having children, either by choice or through circumstance. About a quarter of Australian women in their reproductive years are likely to never have children.

Why are women having fewer children?

There are many reasons why people have no or fewer children than planned towards the end of their reproductive years.

One contributing factor is that the average age when women have their first child has increased in the past few decades, and is now almost 30 years. This is in part explained by women spending more time in education and the workforce than they used to.

Read more: Balancing work and fertility demands is not easy – but reproductive leave can help

Another reason is some women don’t find a suitable partner, or have a partner who is unwilling or “not ready” to commit to parenthood.

It’s also possible limited knowledge about the factors affecting fertility leads to missed opportunities to have the number of children originally planned.

But whatever the reason, having children later in life will inevitably affect the number of children people ultimately have. While most women who try for a baby will succeed, some won’t, and some will have fewer children than they had planned.

Fertility declines with age – so does IVF success

The risk of not achieving pregnancy increases as a woman gets older because the number and quality of her eggs decline.

By 40, a woman’s fertility is about half the level it was when she was 30. And sperm quality decreases with age, too, starting at about age 45.

Increasingly, people who struggle to conceive turn to assisted reproductive technology (ART) such as in-vitro fertilisation (IVF).

There was a 27% increase in the number of treatment cycles in the 2020-21 financial year compared with the previous year, according to data released today by the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA).

But unfortunately, IVF is not a good back-up plan for age-related infertility.

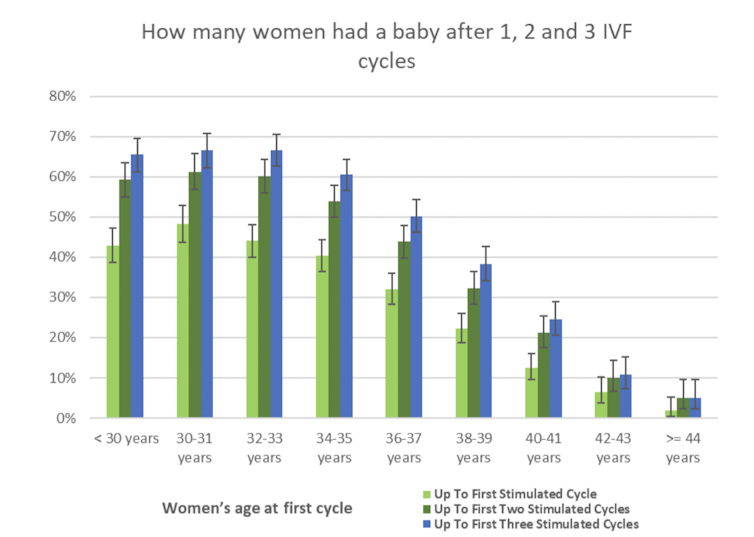

On behalf of the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA), researchers at the University of New South Wales tracked thousands of women who started IVF in Victoria in 2016 to see what had happened to them by 30 June, 2020. The graph below shows the proportions of women who had a baby after one, two or three stimulated IVF cycles, including the transfer of all fresh and frozen embryos that resulted from these.

Women who started IVF when they were 30 years old had a 48% chance of a baby after one stimulated cycle, a 62% chance after two cycles, and a 67% chance after three cycles.

But for a woman who started IVF at age 40, there was only a 13% chance of a baby after one stimulated cycle, a 21% chance after two cycles, and a 25% chance after three cycles.

Fertility options for over-35s

So, what are the options for women in their mid-30s who want to have a child or more children?

The VARTA data reveals some women aren’t waiting to find a partner. Over four years, there’s been a 48% increase in single women using donor sperm to have a child, and a 50% increase among same-sex couples.

But the number of men who donate sperm in Victoria has remained the same, so there is now a shortage of donor sperm.

The option of freezing eggs for later use is also used by more and more women. Almost 5000 women now have frozen eggs in storage in Victoria, up 23% on the previous year.

But it’s important to remember that although having stored eggs offers the chance of a baby, it’s not a guarantee.

For women in their 40s, using eggs donated by a younger woman increases their chance of having a baby. Our study showed women aged 40 and over who used donor eggs were five times more likely to have a live birth than women who used their own eggs.

But finding a woman who is willing to donate her eggs can be difficult. Most women who use donated eggs recruit their donor themselves, and some use eggs imported from overseas egg banks.

So while people might think pregnancy will happen as soon as they stop contraception, having a baby is not always easy.

Read more: Egg freezing won't insure women against infertility or help break the glass ceiling

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.