Tucked behind the Monash freeway, the Nylex clock and the silos on the Yarra lies the manufacturing precinct of Cremorne. The production lines have stopped, but the old business names remain on buildings and signs: Bryant & May, Rosella, Slade Knitwear.

Architects and urban designers Maud Cassaignau and Markus Jung first visited Cremorne in 2011, after living in Zurich for 10 years. They were astonished that so many warehouses, factory sites and cottages remained in their original state.

“What struck us was the diversity of typologies, the feel of it,” says Cassaignau. “It reminded me a bit of industrial areas I had seen in London or in New York – but it was bypassed, people seemingly didn't know it so well. We felt that here was something really precious.”

Jung particularly remembers his surprise that Cremorne’s working-class character was still intact – even though prime sites such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Chapel Street and the MCG were only a stroll away. “That really made us curious,” he says. “Comparable areas in Europe are either gentrified or have been demolished.”

Cremorne has changed rapidly in the years since. Gallery owners, artists and small-scale manufacturers first saw the potential in the unused industrial spaces, which they rented or purchased cheaply. Some of these pioneers have in turn been pushed out by developers and investors.

“Sometimes the properties were kept empty, and there was a sense that they were waiting for an investment boom,” Jung says.

Most recently, tech media companies have bought in. “We heard that they have been lobbying the council to turn the area into a business zone, without housing,” he says.

He and Cassaignau now live in a Cremorne warehouse apartment with their children. They share the building with other families (nine children live there altogether), as well as small-scale manufacturers.

Their wish is to preserve Cremorne’s unique elements while also allowing for more intense residential and commercial projects – they say these are inevitable as Melbourne’s population grows. The designers’ vision of an ideal Cremorne is laid out in their book Building Mixity, Cremorne2025/37.83°S/144.993°E, which they wrote with Matthew Xue.

Mixity is a word the pair have adopted from the French mixité, to express their vision for the suburb. It involves honouring the community and building heritage that already exists in the area, but also envisioning creative ways forward.

Among the residents quoted in the book is Bella Anderson, who moved into Cremorne 16 years ago when property was cheap. She says: “The mix of industrial buildings as well as wonderful structures like the Bryant & May building made it something of an inner urban fairyland with pockets of beauty and decay, cottage gardens, and new architecture and possibilities.”

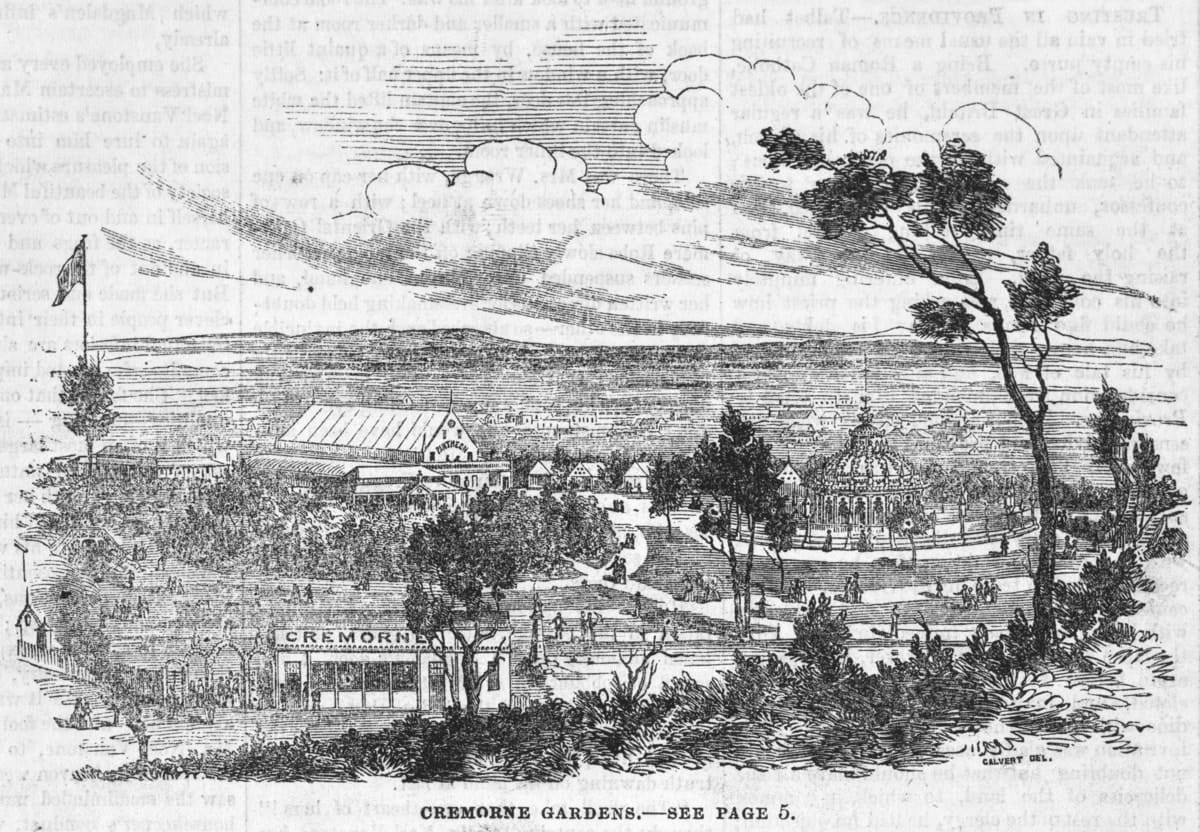

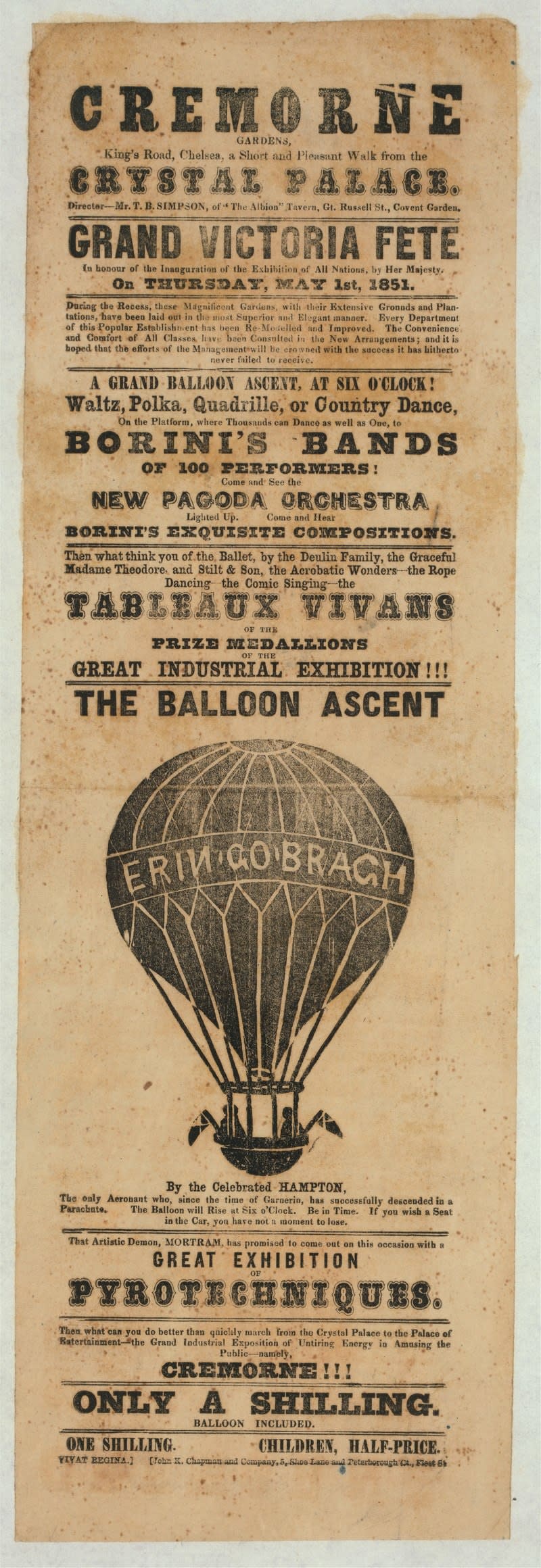

The book begins with a short history of Cremorne. It was once the site of pleasure gardens on the river (now commemorated with a plaque in a playground next to the freeway). The attractions at Cremorne Gardens included restaurants, balloon ascents, a dance floor (along with ladies prepared to be your partner for a price). The gardens could be accessed by ferry, and later by train, which stopped at now defunct Cremorne railway station.

A wish list for the suburb

Building Mixity includes an analysis of the precinct’s building types and suggestions for how they might be reconfigured in the future. It’s also a wish list for how Cremorne might evolve – incorporating ideas from workshops with residents and with Monash research students.

The list includes new infrastructure – such as restoring the train station and the ferry, and building a platform over the freeway to reinstate access to the river (which could possibly be financed, at least partly, through public-private partnerships with developers).

It was once the site of pleasure gardens on the river. The attractions at Cremorne Gardens included restaurants, balloon ascents, a dance floor (along with ladies prepared to be your partner for a price).

Some policy items are concerned with allowing lower-income residents to continue to be accommodated in Cremorne, perhaps by means of rent control. They also propose that owners of empty buildings be taxed to discourage the practice.

Some of their suggested innovations have already been adopted. Last year, Victoria introduced a new planning code for post-industrial areas – Commercial Zone Three – that would allow housing and production sites to co-exist within the same development (which also reduces traffic).

Although the zoning has yet to be adopted in Cremorne, Cassaignau and Jung see it as a means of maintaining the area’s mix of family residences, music venues, creative spaces and small manufacturing enterprises. Cremorne is at a crossroads, they say. Will it continue to evolve as a diverse, lively urban hub? Or will big money be allowed to have its way, regardless of its impact on the streetscape and community life?

A mixed bag

New developments in Cremorne are both good and bad, they say. They largely approve of the new mixed development under the Nylex sign, because it contains apartments big enough for families, and not only singles or couples. It also allows for people to live above their workspace if they choose, and it has shops on the ground level, drawing passers-by into the precinct.

However, they’re less enthusiastic about the new Seek headquarters in Cremorne Street, which incorporates parking and restaurants (for its staff only), overwhelms the streetscape, and blocks views of the city.

Cassaignau and Jung say Tokyo provides an inspiring example of how a city can accommodate intense developments as well as the character and atmosphere of a small village.

“Tokyo has grown gradually, and it's very dense, but it's at a medium-height-density level; only strategic areas have got these high-rise buildings,” says Jung. “Shibuya, for instance, is one of the busiest intersections in the world, but two minutes’ walk from Shibuya station you’ve got the old yakitori restaurant, and people manufacturing things, and the old supermarket … it’s very charming.”

Retaining character

Ideally, as Melbourne grows, the city will retain its individual historic neighbourhoods – Cremorne feels different from Fitzroy and Collingwood, for instance, and from South Yarra across the river.

The book ends with a statement of what urban design can achieve: “We can strengthen our urban centres, rather than challenging them with new green field developments and monotonous inner-city speculation playgrounds. We can challenge investments to upgrade existing urban living areas rather than replacing them with partially vacant developments. We can increase long-term economic and social diversity by offering mixed developments with affordable spaces. We can include opportunities for emerging businesses and industries, and we can direct more effort into cities for living and working, rather than accept an emptiness that awaits speculative investment.”

Building Mixity, Cremorne2025/37.83°S/144.993°E is published by Monash University Publishing.