Could Australia’s housing crisis be solved, not with a bold expensive plan, but with sneaky, under-the-radar remedies? Architectural researcher Alysia Bennett has been working on some strategies she thinks might work.

Dr Bennett knows that more affordable housing is urgently needed. She comes from Hobart, which has the tightest rental market in Australia, and has worked in Sydney, home of the nation’s most expensive real estate.

These days she lives in a leafy Melbourne suburb with her young family. The streetscapes are pleasing; she understands why Save our Suburbs members might object to insensitive developments throwing shadows over their home turf.

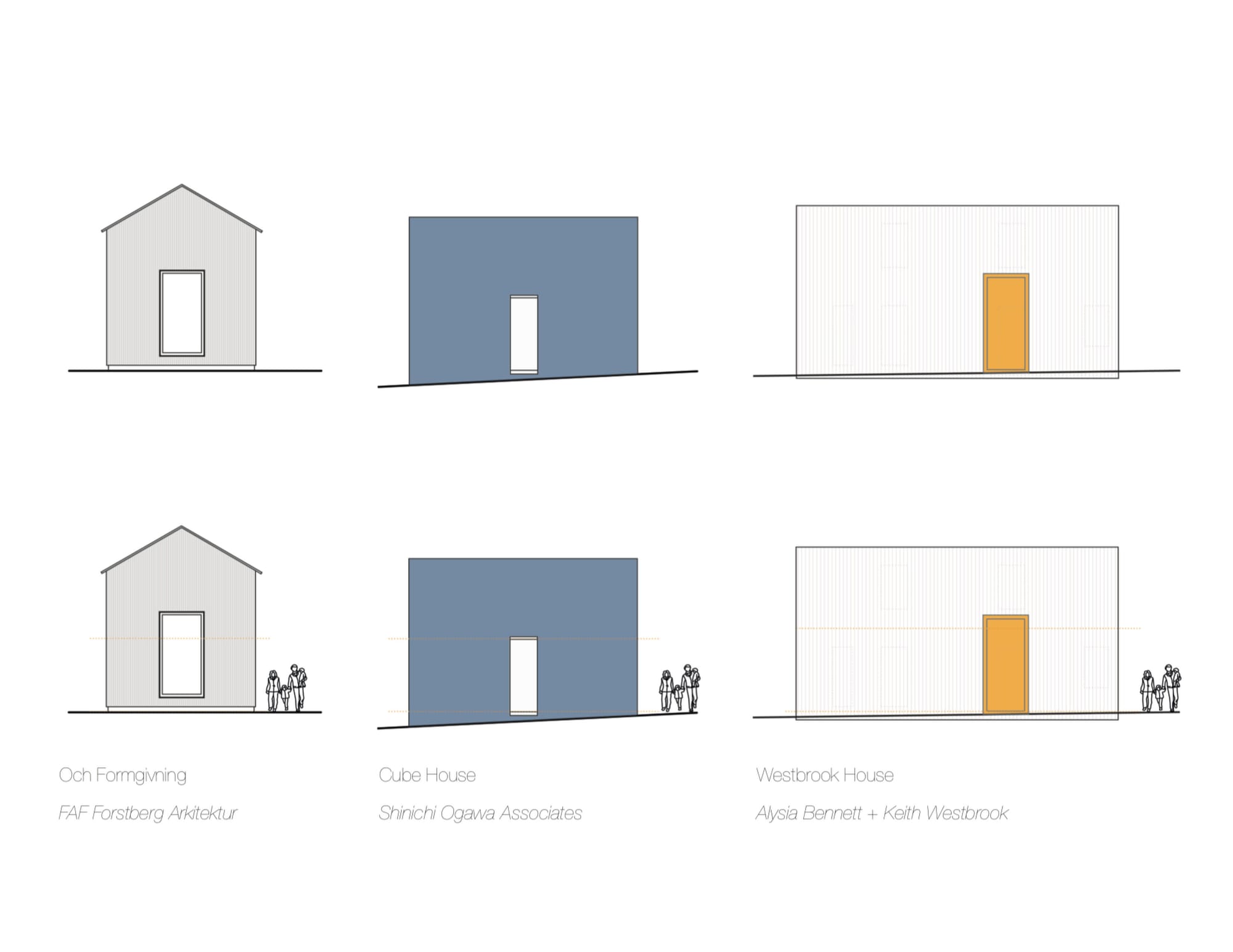

Source: Alysia Bennett

She's been working on solutions that give everybody what they want – cheaper accommodation for those locked out of the housing market, while retaining the original housing stock and the backyard. The strategy involves making simple changes to the floor plans of existing houses to allow smaller households to live side by side. Importantly, the changes she advocates may not require planning approval, but take advantage of the grey areas in existing planning regulations.

“Finding the grey areas isn't necessarily about finding things that are illegal, but actually just removing blockages for types of housing that we actually need,” she says. Stealth Urbanism was the title of Dr Bennett’s doctoral thesis.

The alterations – which might be as simple as moving a door – are potentially within the scope of a DIY enthusiast.

“Whether that's the homeowner physically doing it themselves, or directing a contractor to do a very small renovation,” she says, “it’s what can be done within a household’s means with their available cash.”

A bathroom can be added by installing an en-suite, for instance. Or a small kitchen can be added to a living space by adding a sink, a bench and an inexpensive induction cooktop.

"An apartment block can take five years to develop if you take it all the way from sourcing land to getting it through the planning process – longer if the neighbours object.”

Changes to household demographics make it possible to tackle the housing crisis in this low-key, yet practical way, Dr Bennett explains.

The houses in the middle suburbs typically provided shelter for two parents and two or three children, while new houses on the urban fringes are even larger with four or five bedrooms.

“But the most common household configuration in Australia is one or two people,” she says. “And at the other end of the spectrum, you might have a multi-generational configuration. Say, mum and dad, who might have been empty-nesters, but then the boomerang kids come back, or an elderly parent moves in. Or you might have a couple sharing with another couple.

“In Sydney you’ve got quite extreme conditions, like boarding house configurations, particularly with international migrants who are renting rooms in houses. Or you might have many people, sometimes as many as eight, living in a one-bedroom dwelling.”

Right time for Rightsize

Dr Bennett developed the initiative with the help of Dr Damian Madigan from the University of South Australia, and adjunct Monash Professor Dana Cuff from the University of California, Los Angeles. They put the model forward when the City of Sydney called for alternative housing proposals earlier this year.

Their initiative, called The Rightsize Service, was described as partly a design solution and partly a finance and management model. It made a shortlist of seven, out of 230 entrants.

Because the model combines financing and design elements, it can be adapted in many ways. A Rightsize renovation could be a DIY project started by a father to accommodate his daughter and her child, allowing them to live separately on the same premises. Or a single woman on a pension living alone in a large residence, but who wants to stay in the suburb she's lived in all her life, might apply for community financing to Rightsize her home. In return, the agency would determine the tenant based on need.

Supervision by an outside agency could also ensure the adaptations comply with safety regulations, Dr Bennett says.

Homelessness can be triggered when people are locked out of the rental market because they don’t have a credit history, or a rental history, or a solid employment record. This can be a barrier for casual workers in the gig economy, some new immigrants, and also older women who, before their marriage ended and their children left home, may have been homemakers with a joint bank account. In Australia today, women older than 55 are the fastest-growing category of people experiencing homelessness.

Dr Bennett says all of the finalists in the City of Sydney’s call for alternative housing had viable ideas – ideally, they would all be implemented side by side. Rightsize has the advantage of being quick and easy.

“By contrast, an apartment block can take five years to develop if you take it all the way from sourcing land to getting it through the planning process – longer if the neighbours object.”

Homelessness is on the rise in many cities around the world. In 2017, Professor Dana Cuff co-authored a bill that became law in California, permitting backyard homes, or granny flats, on all single-family properties. This resulted in granny flats accounting for 20 per cent of all new dwellings constructed in Los Angeles in 2018.

Granny flats are another way of productively using existing suburban space, but they're rare in Victoria because of tough and inflexible planning regulations.

“The Rightsize concept does take granny flats into account,” Dr Bennett says. “But we're trying to focus on the internal reconfigurations of houses as a first take.”