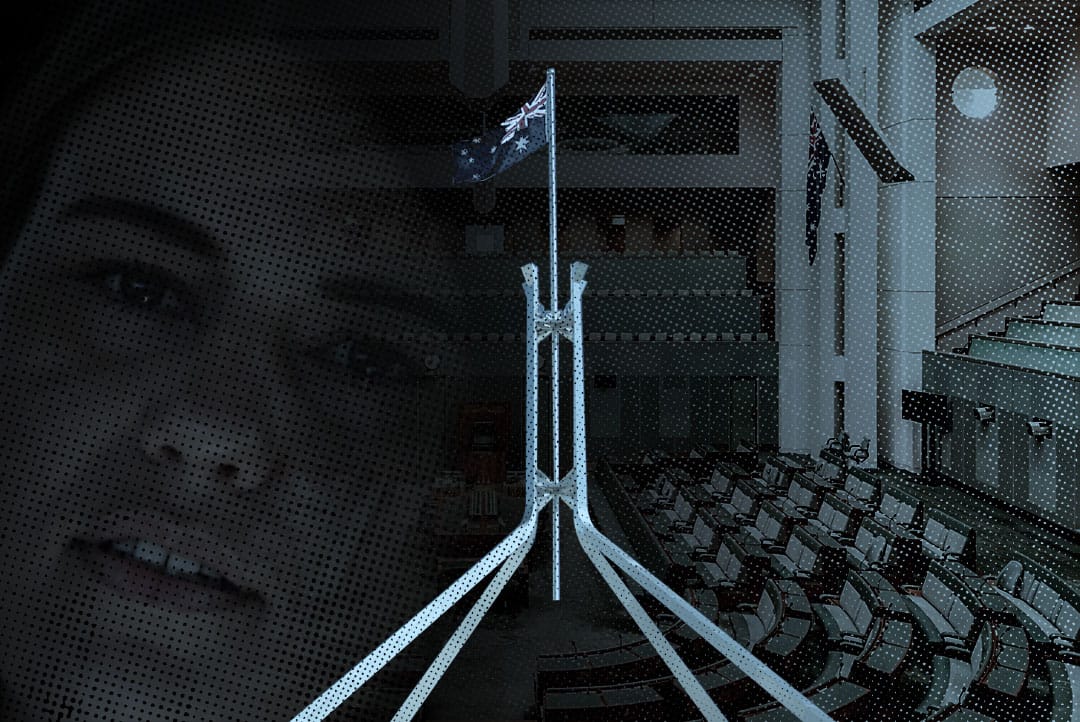

Federal Parliament has long been accused of fostering a misogynist culture. Then Labor Party prime minister Julia Gillard’s 2012 internationally-renowned misogyny speech condemned this culture, and the men in politics that perpetuate and benefit from it.

More recently, former Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins’ public disclosure of an alleged rape in 2019 by a colleague inside the office of the senior minister she worked for galvanised wide spread public outrage.

Higgins went public in February 2021 after feeling unsupported by those in the office she disclosed to, including the minister. The minister was subsequently exposed as having referred to Higgins as a “lying cow”, forcing her to retract the comment and apologise.

Anger over the treatment of Higgins, and the lack of government action to better support victims and hold perpetrators to account, culminated on 4 March, 2021, in rallies around Australia attended by tens of thousands, under the banner #EnoughIsEnough#.

Higgins told those rallying outside Parliament House:

“I was raped inside Parliament House by a colleague, and for so long it felt like the people around me only cared because of where it happened and what it might mean for them.”

Speaking to the media earlier, she indicated that her perception, after disclosing the rape to the minister and senior people in her office, was that she had to choose between her job and seeking justice.

Higgins’ revelations highlight problems in the system for staff who wish to complain about behaviour they’ve endured, witnessed or uncovered in Commonwealth parliamentary workplaces.

So, not only did Kunkel not find what he was not looking for, he backgrounded Brittany Higgins' partner in the report that ‘found’ no backgrounding had happened...

There is no low that is too low for the Liberal/National parties. They disgrace Australia.https://t.co/FTkDdmpvnb— Sir Autumn Mandrake (@AutumnMandrake) 26 May, 2021

These difficulties are not unique to these workplaces.

Focusing on sexual harassment specifically, the 2020 Respect@Work report by the Sex Discrimination Commissioner found that opaque and complex procedures for complaining existed across many workplaces, with victims “often the unintended casualties” of such processes.

But there are additional specific disincentives for parliamentary staff who wish to make a complaint. The Department of Finance is nominally the employer and the department to which staff complain, but it has very limited powers.

It has no powers to sanction a parliamentarian's office, even if a complaint is found to be valid. On the other hand, the provisions of the Members of Parliament (Staff Act) gives individual MPs enormous power to hire and fire staff, allowing staff to be sacked at any time without reason. In addition, the complaint process isn’t independent, because the Department of Finance is accountable to the executive branch of government.

As Higgins puts it:

“The Department of Finance is required to police the conduct of the people who give them directives. This is naturally a conflict and has the potential to inhibit the impartiality of the Department of Finance.”

In December 2020, the Commonwealth Public Sector Union undertook a survey of almost 100 political staffers. More than three-quarters of those surveyed indicated they didn’t believe the Department of Finance would support them if they reported serious workplace incidents. Two years since the alleged rape of Brittany Higgins, there’s been no change to the complaint process.

The lack of effective independent complaints mechanisms has been highlighted by Higgins as a key part of any reform agenda.

She’s recommended an independent parliamentary human resources authority to provide guidance, advice and rulings for MPs at arm’s length to government, and reform of the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act to stop staffers from being fired on the spot, and ensure appropriate cause is used as grounds for dismissal.

What we can learn from United Kingdom reforms

Given the focus on what are widely considered inadequate and ineffective complaint mechanisms for those working in Australian parliamentary workplaces, it’s instructive to consider the significant reforms to such processes that have recently been made in the United Kingdom.

The UK Parliament was the first in the world to introduce independent scrutiny of MPs with the establishment of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards role, and the appointment of lay members of the House of Commons Committee on Standards, as well as the Independent Expert Panel.

Oversight and complaint mechanisms in the UK House of Commons have evolved over time, the impetus for change arising from scandal or public concerns about the behaviour of MPs (for example, the problems around MPs claiming expenses had a significant impact on the reputation of MPs).

The issue of bullying and harassment was brought into sharp focus in a report by Barrister Laura Cox QC in 2018.

Looking specifically at House of Commons staff, she identified:

“… a culture, cascading from the top down of deference, subservience, acquiescence and silence in which bullying, and harassment and sexual harassment have been able to thrive, and have long been tolerated and concealed …”

Complaints were investigated by the Commissioner for Standards (an independent post) and adjudicated by the Committee on Standards, a select committee of the House that contained (non-voting) lay members as well as MPs.

There was, however, a lack of confidence among women in the procedures in place for complaints. It was important, Cox argued, that the most effective way of determining complaints of bullying, harassment, and sexual harassment brought by staff against MPs would be to ensure that MPs had no involvement in the process.

In response to the Cox report, the House of Commons agreed to establish a further independent inquiry to consider allegations of bullying and harassment relating to MPs and their staff.

It subsequently endorsed the creation of an Independent Complaints and Grievance Scheme (ICGS). The new approach included a new behaviour code (in addition to the code of conduct for MPs), a bullying and harassment policy, a sexual misconduct policy, the elimination of the threat of exposure that prevented many coming forward, the establishment of independent helplines, and an increase in the powers of the Commissioner for Standards.

In June 2020, the House approved the establishment of an independent expert Panel to consider cases raised under the ICGS, and in November it approved the appointment of the eight members of the panel.

Investigations and adjudications into complaints about the misconduct of MPs was thus taken entirely out of their hands.

Read more: Brittany Higgins: The #MeToo moment was a wake-up call, but when will we actually wake up?

The independent panel has the power to determine ICGS cases and decide on sanctions. The House of Commons has the final say on any recommended sanctions to be imposed on MPs.

Non-ICGS complaints (relating to the code of conduct) remained the responsibility of the Committee on Standards, in which lay members now had full voting rights (the only select committee of the House to have non-MPs as members).

The creation of an independent panel was a significant step in attempting to improve confidence in the complaints process, though it’s too early to judge the overall impact of the changes.

After meeting with Higgins in April, the Prime Minister stated:

“I am committed to achieving an independent process to deal with these difficult issues.”

The UK provides an example of such a process in stark contrast to the current situation in Australia, which offers no effective avenue for complaint, and thus little protection for those working in federal parliamentary workplaces.

Dr Maguire is a Lay Member of the UK House of Commons Select Committee on Standards. He is writing in a personal capacity. He is also a professor of practice at Monash University.