On 3 December it was International Day of People with Disability, a day dedicated to understanding disability rights, issues and promotion of disability inclusion, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals.

A core focus of this day is to recognise both how far we have come, and the remaining challenges in making inclusion a reality in education, employment, and the community.

To achieve this, we need to celebrate accomplishments of people with disability and the progress made towards disability inclusion.

We also need to examine the uncomfortable truths that make some barriers so hard to shift and leave structural inequity entrenched.

Part of my research during the past year has been dedicated to exactly this, examining the structural and economic barriers within our education system, and understanding where they came from and why they persist.

My research found that eugenics, a theory popular from the late nineteenth century until World War II, had an early but profound influence on educational policy that lingers to this day in the rationale for, and funding of, educational provisions for students with disability.

As a teacher for more than a decade, and a teacher educator and researcher in this field for more than a decade, I am intimately acquainted with the desires, frustrations and beliefs that people hold regarding the education of young people with disability.

In my experience, I tend to find that through genuine and respectful discussion, we agree on more points than we differ.

Students with disability can be some of the most disadvantaged in the system and can grow up to have some of the poorest post-school outcomes regarding rates of further study and training, employment, independent living, health and incarceration.

What I have found during my years in secondary and higher education is that we all agree that these shocking outcomes need to change.

Some of the people who contacted me argued that I was proposing a flawed theory or set of beliefs. Yet my recent research is not based on theory or beliefs nor does it offer any.

Rather, I analysed historical documents from policy and published research to understand how public education began and how we ended up with segregated ‘special’ schools in Victoria.

What I learnt is that Victoria’s legislation is unique, arising from the vision and tenacity of a radical conservative, Justice George Higinbotham.

After chairing a royal commission into public instruction, Higinbotham successfully convinced the voting public and legislators that to address rising crime and increasingly divisive sectarianism, a state-funded compulsory, secular and free education for all children must be provided.

Yet this vision was never realised for young people with disability, many of whom were, from the outset, segregated into separate institutions.

Such segregated settings have persisted in the face of decades of evidence that students with disability achieve better social and academic outcomes from receiving their education in mainstream schools.

They have persisted despite national disability anti-discrimination legislation and standards for compliance for schools which permit segregation under a special exemption clause. And they have persisted in the face of international human rights obligations to cease running a dual-track system of ‘special’ and ‘mainstream’.

My research found that segregated schools and classrooms came into being because of concurrent historical circumstances.

At about the same time that Victoria’s public education act passed, Galton’s theory of eugenics was published and became immensely popular.

Sir Francis Galton’s pseudoscientific views that certain races and ‘feeble-minded’ people were defective and were more disposed to criminality were promoted around the world, including by the Australian Medical Association and their state-based counterparts. These had a profound influence on educational policy.

In direct contrast to Higinbotham’s proposal that education be universally provided to reduce criminal behaviour, Galton argued that people with disability were hereditarily prone to criminality. He advocated for curbing these unwanted traits in the human race through selective breeding, isolation and control by segregating them for the good of society.

Eugenicists argued that to achieve mass identification of ‘deviant’ people, a scalable system of screening was needed and set about developing the tools through which these decisions could be made about who was ‘defective’ and who was not.

Accordingly, a booming industry of testing for defects in children arose and recommendations for policies and practices to achieve segregation and exclusion.

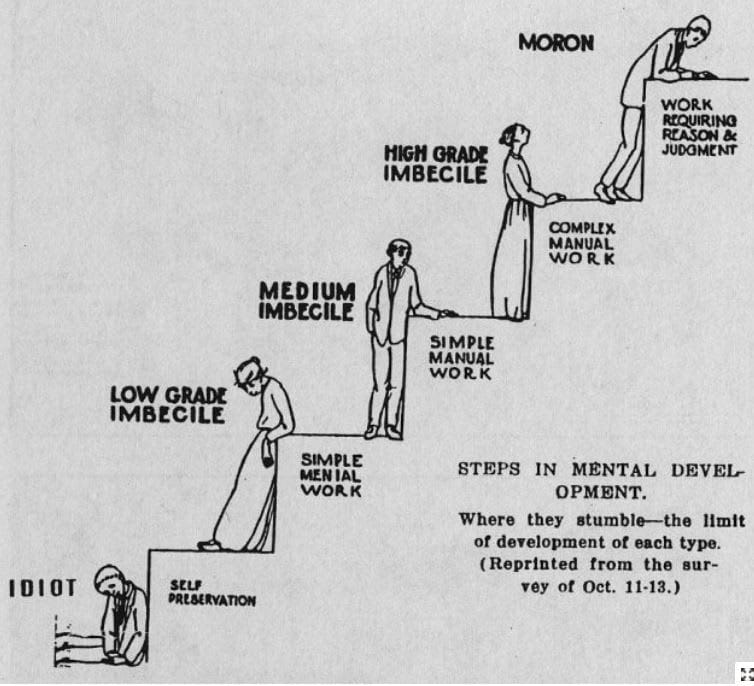

The rise of the testing and assessment industry was fuelled by the work of eugenicists such as Henry Goddard, Stanley Porteus and Edgar Doll.

In their work at the Vineland Training School for Feeble-Minded Boys and Girls, they expanded Binet’s Intelligence Quotient (IQ) assessment, used to calculate a ‘mental age’, and place students into categories of ‘feeble-mindedness’ (Kearl, 2016; Kline, 2014). based on their usefulness to society in carrying out work.

The tests that developed for mass screening for defects remain widely used today, such as the Burt Word Reading Test, the Porteus Maze Test, and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.

At the time, these assessments were used to screen for defects and to isolate people into residential institutions and to protect broader society under the Mental Hygiene Act.

Institutions such as Melbourne’s Janefield Colony for the Treatment of Mental Defectives were built and expanded, justified on the basis that in doing so they were keeping society safe and improving the human race.

The more tests were developed and the more children were screened, the more the demand for separate placements rose and the more that were built.

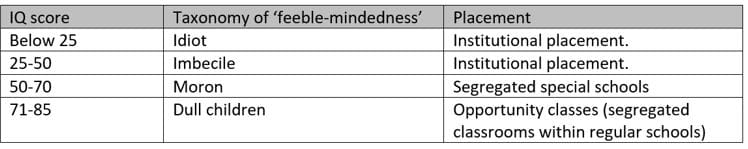

Mirroring the expanded taxonomy of ‘feeblemindedness’ developed by Goddard, and his selection of the number 70 on the IQ scale as the point at which feeble-mindedness began, the Victorian Department of Education developed a suite of increasingly segregated placements for people with disabilities that can be summarised as follows:

In my research, I found that following the end of World War II, when eugenics had been thoroughly discredited, moral arguments continued to be espoused to justify the systemic segregation of children with disability.

While challenging the notion of heritability in relation to disability, and using terms seen to be more palatable at the time such as ‘handicapped’ or ‘retarded’, segregation continued to be championed as offering welfare and treatment for children with disability and many continued to be regarded as ‘ineducable’.

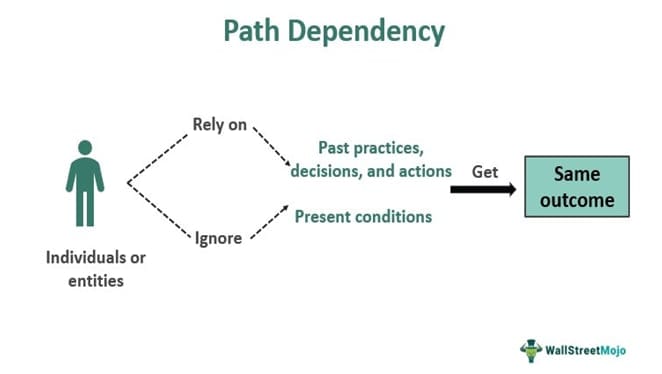

My research found that since that time, segregated education for students with disability in Australia has become path dependent, with prior events and decisions made in the past continuing to influence conclusions as a result of limited understanding or anxieties about costs, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Path dependency is well-known in the field of economics, but equally applicable to other fields such as social sciences, including education.

Today, educational provisions for students with disability remain in a long shadow cast by the darker parts of history, cloaked in respectability woven only by the passage of time, their origins obscured and almost forgotten.

The same tools – the IQ test, the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scale – continue to be used to classify and segregate students using the same cut points developed by eugenicists to determine ‘feeble-mindedness’.

These have become embedded within funding models for providing support for students with disability, such as Victoria’s criterion of a score below 70 on a Vineland assessment within the eligibility criteria to receive targeted funding under the Disability Inclusion reform

They also remain the decision-making tool for determining the eligibility to enrol students into the suite of increasingly segregated settings in Victoria. Typically, students are deemed eligible to enrol in Special Schools if their IQ is between 50 and 70, and in a Special Developmental School if their IQ is lower than 50.

'This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to finally create a single system that provides appropriate support for all children, addresses structural inequity, and achieves societal change.'

It is time to remember the origins of these criteria for enrolment and re-examine their relevance. Path dependency scholars argue that to address ongoing and institutionalised cycles by which decisions of the past persist into the present, the mechanisms that maintain the cycle must be challenged.

We must combat ignorance with information, challenge false beliefs, and remove the perverse incentives within funding mechanisms that institutionalise segregation.

We can achieve this by drawing back the curtains and letting the sunlight in, chasing away the historical shadows that shroud unchallenged conventions in segregated education, re-examining the rationale for our actions and using evidence to drive our actions.

These tools and decision scores are only used because they always have been, they offer nothing but history and convention.

IQ and adaptive behaviour assessments do not inform the particular supports that students require to make progress at school. They are not aligned to the curriculum and they do not offer any guidance on instructional strategies.

We do not need them and we have much better alternatives already being developed.

One example is Victoria’s new tool for determining the intensity and types of support students may require to participate in educational activities.

To abandon these outdated tools and adopt newer ones based on a needs-based logic will require change at scale, political bravery, a roadmap to reform, and a commitment to basing policy on robust evidence.

The means of such progressive and scalable change is offered by existing approaches adopted internationally, such as the multi-tiered systems of support.

Victoria’s education system was born of an equally radical and progressive aim for education and was catalysed by the findings of a royal commission. Given that we are, once again, in the throes of a royal commission, there is the promise of hope and change that seems tantalisingly close.

Let’s hope that Higinbotham’s vision can inspire our commissioners and politicians to make brave and progressive recommendations to end segregation.

This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to finally create a single system that provides appropriate support for all children, addresses structural inequity, and achieves societal change.

Let’s hope that the next International Day of People with Disability can celebrate some steps to making these a reality.