Despite the absence of clear climate or energy policy over the past 10 years, the Australian energy market has experienced a series of transformational disruptions that have fundamentally changed its nature.

The centralised ‘base load’ coal-dominated business model of the past 50 years is defunct, and an incredible opportunity now lies ahead to reimagine how we generate, purchase, store and share clean energy within an affordable system powered by businesses, communities and individuals.

A decade ago, the sector was relatively stable. Large coal and hydro generators, mostly built and paid for by government many years earlier, dominated the market, with gas generators burning cheap gas supporting the summer peak periods. Wind and solar power were just emerging in Australia and considered a relatively expensive novelty.

But the state of play was about to change.

The first disruption came in the form of slowing demand driven by a global economy reeling from the global financial crisis (GFC), global manufacturing migration, and advances in energy efficiency technology.

By 2014, demand had bottomed out and the wholesale market was operating close to the marginal cost of generation. For large ageing power plants with looming refurbishment requirements, this period of operation tested their long-term viability, and consequently, in 2015, we saw the closure of the first major coal station, in South Australia.

This tipping point irreversibly changed the South Australian market, and with strong state government leadership (now bipartisan), the state was set on a course to become a global leader in renewable energy transformation.

The next disruption came shortly after, with the start of natural gas export from the eastern seaboard heralding a rapid rise in energy prices. With exporters buying up gas to meet international contracts, prices for large gas users – including Monash University – tripled. Electricity prices quickly followed as the cost to run gas generators to meet peak demands shot up in an increasingly undersupplied market. The effects of this are still being felt today.

During this time, wind and solar power were penetrating the market at scale, helped by falling technology costs and state government support.

The combination of new variable generation coupled with a large uptake in air-conditioning resulted in a significant change to the shape of our energy demand – a more dynamic profile with higher peaks and lower troughs.

Unlike fuel-based generators, the cost of renewables is primarily driven by the financing costs of building the plant, as operating costs are very low (near zero). This means that once established, it still makes financial sense for a renewable facility to continue generating energy even if the wholesale market is very low.

Also, for generators eligible to generate renewable energy certificates, it can be worth generating even if the wholesale market goes negative (for example, in situations where generators pay to put power into the grid), as they can sell the certificate on the secondary market and still make a net profit.

For coal generators already struggling and unable to easily ramp up and down generation, this change further undermined their viability. Consequently, Hazelwood Power Station closed, and a ‘pro-free market’ federal government scramble ensued in an attempt to prop up the very industry with the greatest contribution to climate change.

Despite their best efforts, the writing was on the wall, and a series of closures is confirmed for the coming years, with all of the major generators and lending institutions in agreement that a business case for coal generation no longer exists.

So, after a series of disruptions, we find ourselves in a market where:

- large coal power stations are exiting the market (predominantly those built and paid for by government before being privatised)

- high internationally driven gas prices are pushing up the top of the market

- new low-cost capacity in wind and solar power is pushing down the base of the market, creating dynamic wholesale prices contingent on weather conditions.

Rather than federal government providing a steady hand through clear and consistent energy policy, we’ve seen the disruption exacerbated by investment uncertainty created by partisan-factional politics.

As a result, we’re experiencing periods of abundant, cheap wholesale electricity mixed with periods of extremely expensive power, destabilising the traditional retail business model and increasing prices for consumers.

In South Australia, where renewable energy generation is rapidly approaching 75 per cent of the state’s energy mix, new market opportunities are emerging for large companies with dynamic load, generation assets and storage capacity.

By using and storing power when it’s cheap, and generating down when prices are high, these companies are effectively neutralising their multimillion-dollar energy bills through active market participation.

Across the country, we’re seeing large energy users insulating themselves against a dynamic market by proactively building or using their purchasing power to underwrite solar and wind farms to take advantage of predictable low-cost energy.

A sustainable energy market horizon

With the market irreversibly changed, we now have the opportunity to imagine something new.

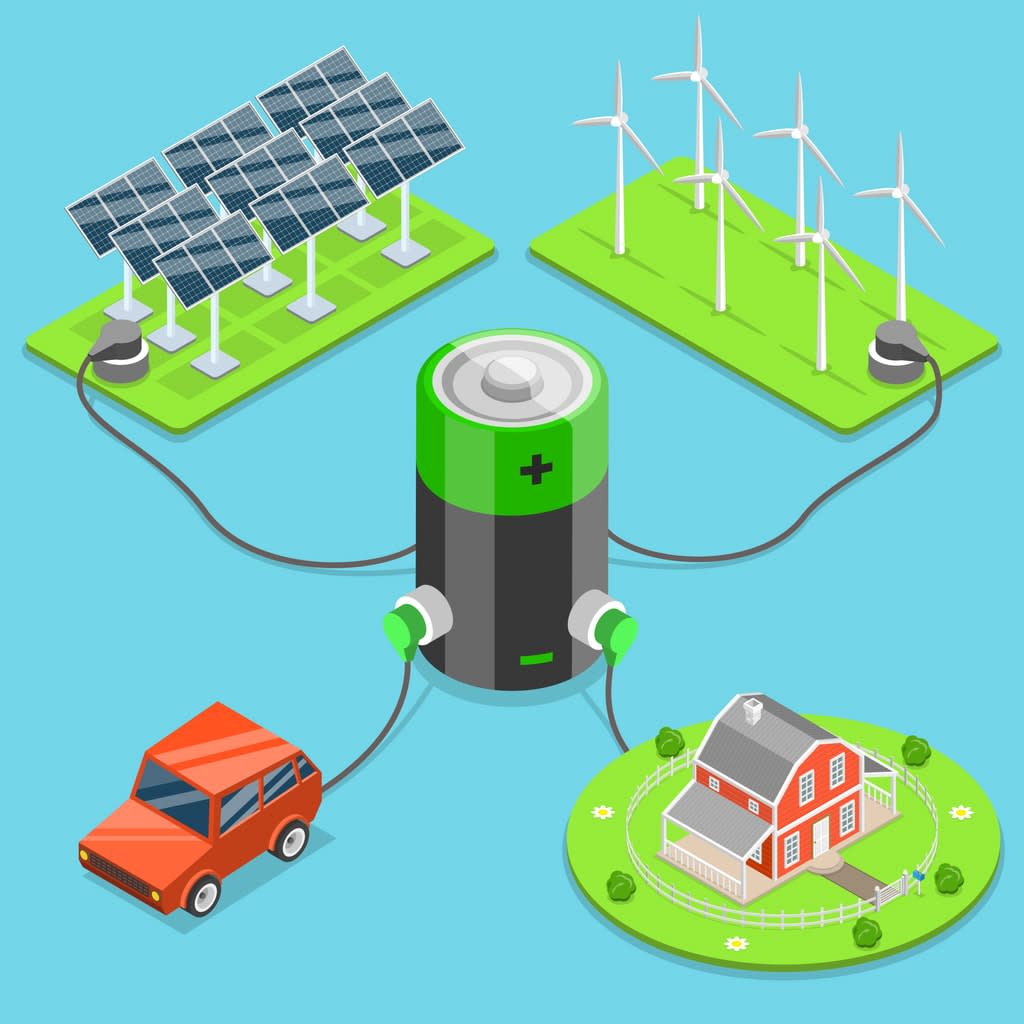

Contrasting with the traditional model of centralised one-way flow of power from generator to user, with generation following relatively smooth and predictable consumer demand, we’re moving towards a decentralised model where the grid and market is made up of interconnected energy precincts dynamically generating, storing and using energy.

A market-driven collective of self-managed energy hubs is emerging to solve local requirements and trade between precincts to create a national network where generation and demand follow each other.

A series of closures is confirmed for the coming years, with all of the major generators and lending institutions in agreement that a business case for coal generation no longer exists.

These precincts would likely include community organisations comprising residences with roof-top solar, domestic energy storage batteries, smart devices and community-funded wind or solar farms, working together as a virtual power plant to support the local and broader network while providing power and market opportunity for residence and investors.

Such precincts would be balanced at a state or national level by complementary precincts such as renewable generation hubs made up of wind and solar generation, balanced by large-scale storage or embedded microgrids such as Monash, with a private network of high-energy buildings, solar generation and storage.

Read more: Can blockchain transform the energy industry?

Each precinct would optimise for local stability and energy requirements while collectively solving national balance through an interconnected dynamic market of diverse participants.

Moving from a vertically integrated oligopoly to a distributed system thriving off the bespoke efficiencies and opportunities of individual communities, organisations and businesses can collectively create a resilient, competitive and sustainable national energy market.