Paige Druce has spent a lifetime on both sides of the operating theatre door. Born with transposition of the great arteries, she underwent her first open-heart surgery at just 10 days old and a second operation at six.

Much of her childhood was spent in and out of hospital – an experience that, while challenging, also sparked a curiosity about health, science and the inner workings of the medical system.

That early exposure ultimately guided her to undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in science, and into a career in clinical trials.

Her lived experience as a patient has never sat apart from her professional life; instead, it’s shaped how she approaches research questions, patient engagement and the ethics of trial design.

“My journey as a patient began the day I was born,” she reflects, “and it’s influenced every decision I’ve made since.”

Her perspective deepened further when her father suffered a heart attack and required a triple bypass operation. Travelling from Melbourne back to her home town in Queensland to help care for him, she found herself once again navigating the system, this time as both a carer and a researcher.

The experience reinforced something she already believed to be true – patients and their families hold critical knowledge that can strengthen clinical research.

“Because I’ve been a patient and a carer,” she says, “it’s important to me that patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives are incorporated into the work that we do.”

The value of lived experience

That is the lens she brings to the PUMA trial, which seeks to answer whether the routine use of a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) in low-risk cardiac surgery patients is justified.

She advocates for research that’s not only scientifically rigorous, but also grounded in respect, relevance and transparency. For decades, cardiac surgery has relied on invasive monitors that promise precision, but carry risk.

As a lived-experience investigator, she’s worked with clinicians to co-design the trial around outcomes that matter to patients – safety, recovery time, clarity about what each procedure adds – and what it might take away.

“As a patient, you want to feel confident that every procedure is truly necessary,” she says. Confidence, she argues, should be earned with evidence, not inherited from tradition.

Bridging two worlds

Druce’s story is the bridge between two worlds often kept apart – the day-to-day reality of heart surgery and the rigour of modern clinical science.

Her presence anchors PUMA in the lived experience of the people it aims to serve, while holding the research to a higher bar; one that measures benefit not only in numbers, but in days at home, trust at the bedside, and the right care, at the right time, for the right reasons.

By integrating consumer voices from the outset, Druce hopes the trial will serve as a model for how cardiac research can evolve – collaborative, patient-centred and attuned to the real-world experiences of those it aims to help.

Australians who undergo open-heart surgery are among the sickest patients in the health system. Their operations are complex, resource-intensive and often lifesaving, but they also come with significant risks, including prolonged stays in intensive care, serious complications and long recoveries away from family and work.

The question of the catheter

Despite major advances in surgical techniques and postoperative care, some of the tools routinely used to monitor these patients have changed little in decades, and their benefits are increasingly being questioned.

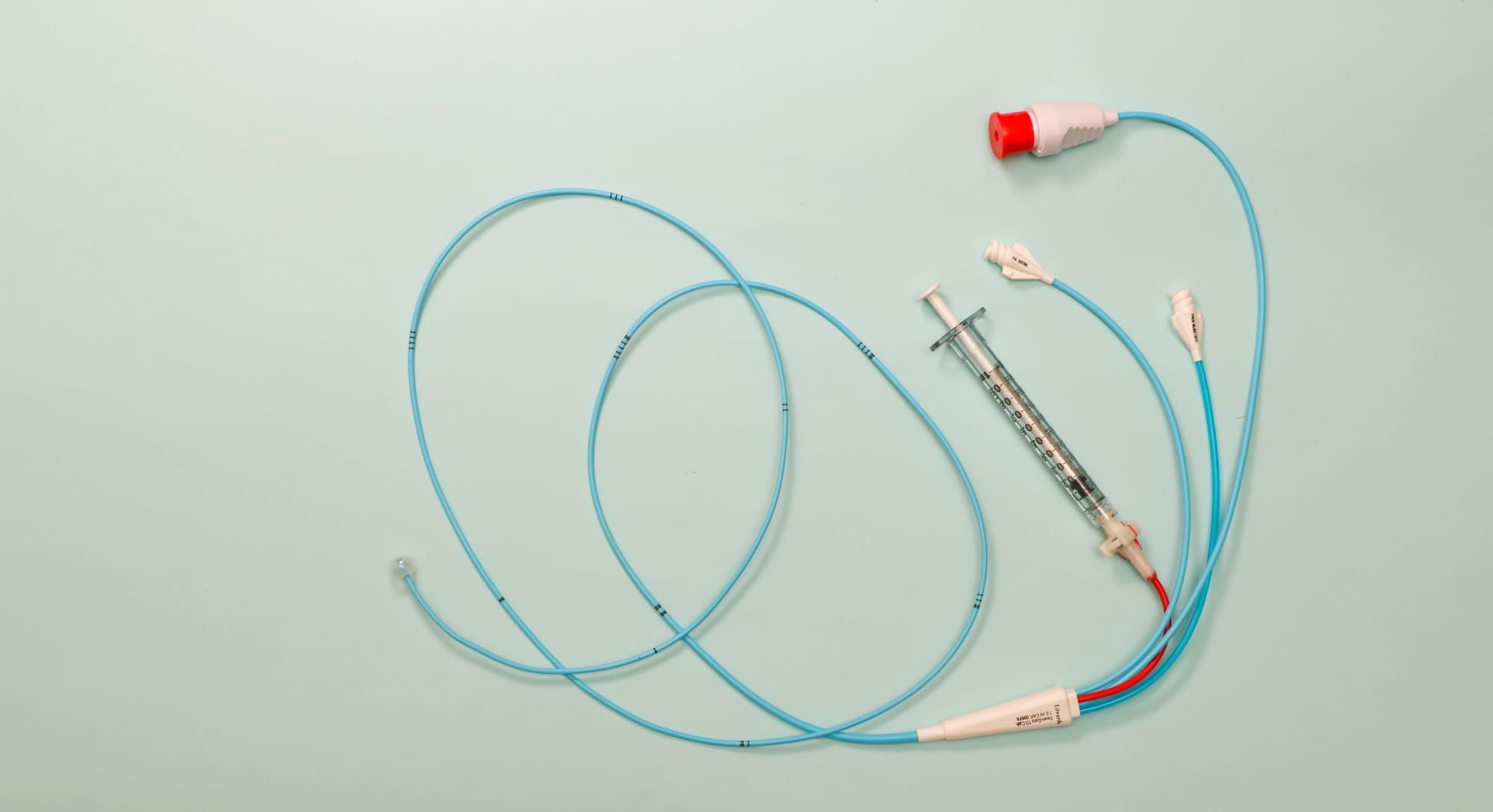

The pulmonary artery catheter, a long, flexible tube threaded through a vein in the neck and into the heart and lungs, is one such tool.

For years, it’s been considered a gold standard for monitoring heart function during and after major cardiac surgery. By measuring pressures inside the heart and pulmonary artery, clinicians can make decisions about fluids, medications and life-supporting treatments. But the device is invasive, technically demanding and not without risk.

Across other areas of medicine, similar invasive monitoring devices have steadily fallen out of favour.

Large international trials in critically ill patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome and those undergoing non-cardiac surgery have failed to show that pulmonary artery catheters improve outcomes.

In some cases, their use has been linked to unnecessary treatments, higher complication rates and longer hospital stays. As a result, many specialties have moved on, but cardiac surgery has largely been left behind.

A lack of monitoring evidence

Each year, more than two million people worldwide require open-heart surgery to treat life-threatening conditions such as blocked coronary arteries or failing heart valves. Yet, despite the scale of this population, there remains a striking lack of modern, high-quality evidence to guide one of the most fundamental aspects of their care – how best to monitor the heart during recovery.

That gap in evidence is what the new Australian-led PUMA clinical trial aims to address.

Researchers from Monash University’s Victorian Heart Institute have been awarded a $3.7 million grant from the Medical Research Future Fund to lead a world-first study known as PUMA.

The trial will compare the traditional pulmonary artery catheter with a simpler and less-invasive alternative – the central venous catheter – to determine whether the added complexity and risk of the older device actually translates into better outcomes for patients.

Lead investigator Dr Luke Perry, Head of Anaesthetic Research at the Victorian Heart Institute, says the field of cardiac surgery has been waiting decades for this kind of definitive evidence.

“These invasive devices have been broadly de-adopted in other high-risk patient groups after large clinical trials failed to show a benefit to patients,” says Dr Perry. “Cardiac surgery is decades behind, and PUMA will finally catch the field up.”

Too much information?

Central venous catheters are already widely used in intensive care. Inserted into a large vein, they provide access for medications and basic information about blood flow without entering the heart or lungs.

While they don’t deliver the same level of detailed data as pulmonary artery catheters, proponents argue that modern imaging, blood tests and clinical assessment may make that extra information unnecessary.

According to Associate Professor Lachlan Miles, Head of Research in the Department of Anaesthesia at Austin Health and a co-investigator on the trial, the question is no longer whether pulmonary artery catheters provide information, but whether that information helps patients.

“Pulmonary artery catheters give unique insights into heart function,” he says. “Unfortunately, they’re not without risk, and they could even trigger unnecessary treatments, increase complications and prolong hospital admissions.”

A distinctive co-design model

What makes PUMA distinctive is not only its scale – a planned enrolment of 2000 patients across Australia and internationally – but also how it’s been designed.

Over the past three years, the trial has been co-designed with patients and their families through the Victorian Heart Institute’s Community Pulse platform. Consumers have been involved at every stage, from early workshops and surveys to a formal co-design symposium.

The result is a study shaped around what patients say matters most – surviving surgery, avoiding complications and getting home sooner.

At the centre of this consumer-led approach is lived-experience investigator Druce, whose perspective has influenced the trial from its earliest pilot phase.

As both a patient advocate and a researcher, she says co-design helps ensure clinical trials are not just scientifically rigorous, but also ethically grounded.

“As a patient, it’s important to feel confident that every procedure is truly necessary,” she said. “Co-designing clinical trials with people who have lived experience helps make sure the research focuses on what matters to the people it’s meant to help, and that it’s done in a way that feels fair and respectful.”

That sentiment is echoed by participants such as Anne, a heart surgery survivor who took part in the PUMA pilot study.

For her, involvement in research was a way of giving back while also restoring trust during a frightening period of ill health.

“When you’re experiencing bad health and have worrying feelings, research helps you feel confident you are in the best hands,” she said.

A broad coalition

The trial brings together an unusually broad coalition of partners, including the ANZCA Clinical Trials Network, Monash Health, the University of Melbourne, Weill Cornell Medicine, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, and international collaborators such as MIT.

Patient advocacy groups, including the Heart Foundation, hearts4heart, Heart Support Australia and Her Heart, are also closely involved.

If the study shows that central venous catheters are just as effective, or safer, than pulmonary artery catheters, the implications could be significant. Reducing unnecessary invasive procedures could shorten intensive care stays, lower healthcare costs and improve patient recovery.

There may also be environmental benefits, with fewer devices and interventions contributing to a smaller carbon footprint for intensive care by 2030.

Recruitment for the PUMA trial is scheduled to begin this year. For patients facing open-heart surgery, the findings could help redefine what “best practice” really means and ensure that the care they receive is guided not by tradition, but by evidence that puts their safety, recovery and lives first.