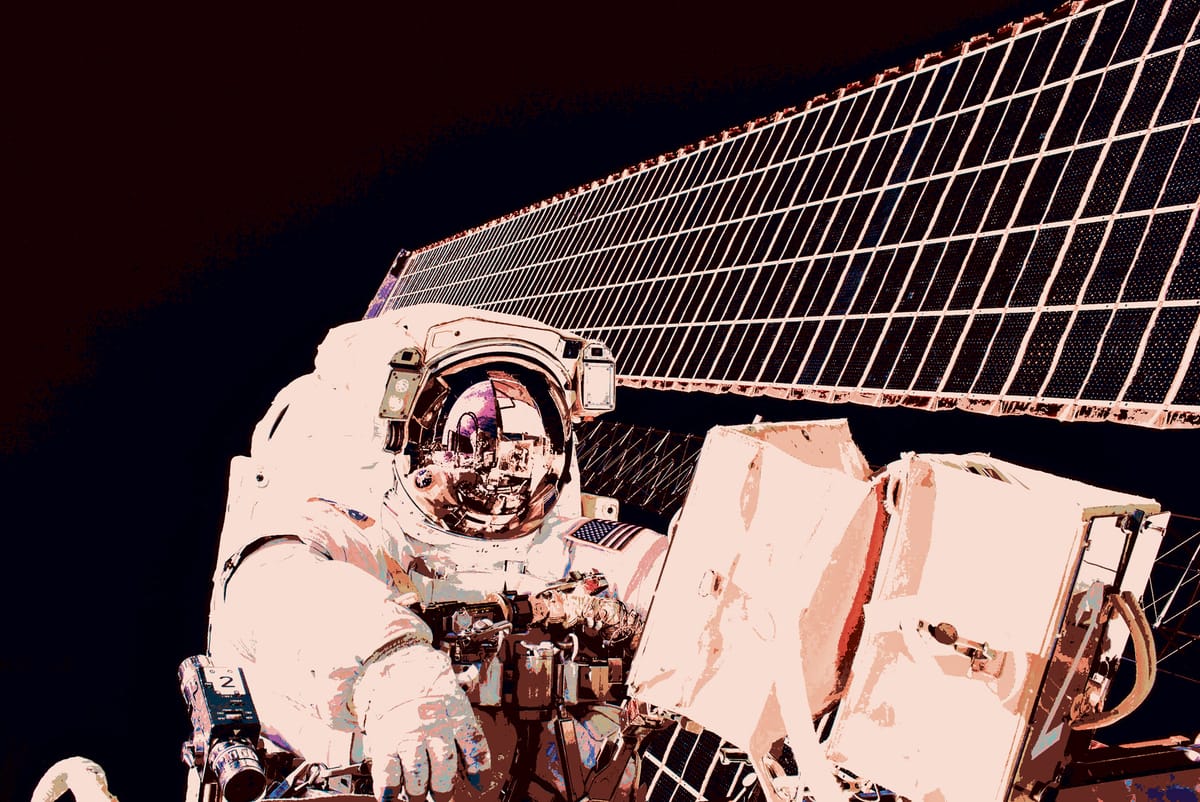

What if we stop exploring space? What do we lose? What are the opportunity costs? What’s next for space exploration and what could it tell us/do for us? How can it make our lives better?

This theme will look at why space exploration not only helps us understand how we came to exist, but can also help us solve some of the biggest challenges we face here on earth. We'll talk to experts ranging from astronomers to architects about why it's vital we keep exploring beyond the earth.

"I think if we stopped exploring space and stopped appreciating space, we wouldn't really have a sense of where we are in the universe. And both the significance and insignificance of us, the rarity of life in the universe."

Michael Brown, observational astronomer

Transcript

Susan Carland: This time on what happens next, we’re exploring space. Not physically, sadly, but its impact on the world we live in today and the way we live in the future.We'll look at why space exploration not only helps us understand how we came to exist, but it could also help solve some of the biggest challenges we face here on Earth. Now we'll talk to experts ranging from astronomers to architects about why it's vital we keep exploring beyond the Earth. In this episode, we'll talk to astronomer Michael Brown. Michael is an Associate Professor of the School of Physics and Astronomy in the Monash Faculty of Science. We'll find out what happens if we stop exploring space. What do we lose? What are the opportunity costs? And is the sun really going to die? Let's hear from Michael Brown.

Michael Brown: Hello, I’m Associate Professor Michael Brown. I'm an astronomer at Monash University and I study how galaxies grow and evolve over cosmic time.

SC: Associate Professor Michael Brown, what's the problem with us no longer exploring space?

MB: I think if we stopped exploring space and stopped appreciating space, we wouldn't really have a sense of where we are in the universe. And both the significance and insignificance of us, the rarity of life in the universe, the fact that, you know, the atmosphere of the earth is just this incredibly thin layer on top of the planet, the fact that things are finite, in some sense the sun has a finite lifetime. The Earth has finite resources, but also that the universe is spectacularly old, spectacularly large. So there's much to explore beyond this. So I think if we stop looking at space, stop exploring space, we have a loss of perspective that we've only recently gained.

SC: Are there things about ourselves, our future, that maybe would be lost?

MB: We’d certainly lose a sense of where we came from, the sense of the entire universe. You know, the big bang is sort of central to how we understand our place in the universe now, the fact that the earth is many billions of years old, that life has been on Earth for many, many millions of years and that our existence on the Earth has only been for a very small amount of time. I think that very big perspective has been informed by astronomy and space, and then the fragility and uniqueness of the Earth, when we look at the earth from the moon and see that blue ball, we compare that to the other lifeless planets, there's something really, really important there that I think we really need to hold on to.

SC: How has space exploration shaped our understanding of our lives?

MB: I think there's a couple of different ways that it informs how we look at our lives. So I think there's a couple of, sort of the mundane aspects, so we're so used to weather forecasting now that we expect to have a pretty good seven day forecast. And part of that is because we have all this wonderful data from the satellites that can inform meteorologists about what's going to be happening and that's sort of mundane in a way, it's like, ‘should I plan a picnic Saturday?’ it would be nice to plan a picnic for Saturday, come to think of it, but hey. But that sort of mundane aspect, which just sort of comes in, you know, we use the GPS to navigate somewhere new. But then there is that bigger picture as well, that informs our lives. So things such as climate change are informed by measurements of satellites, measurements of the atmosphere, of the Earth, the fact that the Earth is so, that the atmosphere is so thin compared to the Earth as a whole, you know, that there's really this tiny layer of atmosphere on top of this ball of rock and that’s so unique in our solar system. So it works on a couple of different levels, a couple of very different time scales. It could be a picnic next week, it could be the future of the sun in billions of years.

SC: Do you feel positive about the future of space exploration? Do you think there's enough societal and political will for it?

MB: I think there is. I think it’s changing and the purposes of space change and so that when we think of the sort of start of the space race and the Apollo missions, it was very tied up in cold war politics, it was about people planting flags, etcetera, and we could see also an era which is very much driven by science and space exploration - space probes going to all sorts of planets, Rovers on Mars, spacecraft going to Saturn or flying past Neptune, Pluto, driven by science, which could be about putting out planet in the context of all the other planets. It can be just about pure curiosity, you know. And then we have the commercial aspect as well, which I think is sort of coming to the fore now where communication satellites, internet satellites, perhaps even space tourism and that is a driver for space exploration. And, you know, at some point in the future, the survival of the human race is gonna have to be driven by space exploration because in billions of years from now the sun is not going to be as tolerable for life as it is now. And so, at some point, if humanity or the descendants of humanity are to survive. We have to move beyond the Earth. And, you know, that's gonna be driven by just survival and not just exploration or commercial interests or or curiosity.

SC: Do you think we're moving in that direction fast enough?

MB: It's always sort of hard to tell where the momentum is going right now and where the priorities should be. Human spaceflight isn't as central to the story of space right now as it used to be, and it's not necessarily clear that that's a particularly good or bad thing. Putting people into space is very, very expensive. People are very, very fragile. Space is not a particularly pleasant place for fragile people. So perhaps having it driven by robots, by the commercial aspect is okay, I guess at some point people traveling in space has to become part of what we do, so whether that happens in the next few decades or, you know, in centuries, people on Mars, that sort of thing, well, we’ll have to see.

SC: What criticism about space exploration really annoys you?

MB: What really annoys me? Oh, I'm just trying to think. I'm not necessarily sure that the criticism sets me off. Besides, I think there's a lot of valid criticism of space exploration. It can be extremely expensive. It can be a rich guy's game. It can be used for purposes that aren't necessarily altruistic. So, you know, spy satellites and things like that. And so some of those criticisms are totally valid. I'm not sure that criticism necessarily annoys me, per say, and I think that it's worth having a debate. I think the criticism that perhaps ‘this money is going on a Mars rover when it could be used to feed the poor’. I think that, yeah, it's an interesting argument to make, but I think it's somewhat of a false dichotomy because often the people making the criticism aren’t actually donating money to the poor themselves. It’s a bit of a weak argument to make. And I do think that there's - you know, we can walk and chew gum at the same time, and we should be doing better on Earth to look after people in poverty, you know, food poverty and food security, etcetera. But our lives are enriched by science, by art, by curiosity, by knowing where we are in the universe, and I think that's worth spending money on. So to see if there was once life on Mars, I think, is worth spending a lot of money on. It's also worth spending a lot of money on improving food security. I don't think that's a one or the other choice. So maybe that's the one that sets me off.

SC: What about the criticism that if Hollywood has told us anything, it's that aliens will definitely want to kill us?

MB: That's an interesting one. I certainly wouldn't - how should I put it - I'd be a little bit cautious about broadcasting messages to aliens if we found them. I think, not necessarily because they would or wouldn't want to kill us, just because, you know we don't know…

SC: Yeah, we don't wanna look too eager. Like maybe they should make the first move. And we should just, you know, be chill about it?

MB: Yeah, exactly. You know - if they send a message to us on Saturday night, we don't … you know, we chill. We don't send something on Sunday morning, that would look wrong. You know, you wait til Monday, Tuesday, that kind of thing.

But It is something that we would have to seriously contemplate if we received a message from an alien civilisation, do we respond to it? On the plus side, if we are, if we have concerns about alien civilisations, from the looks of things there is probably not an alien civilisation, that’s at least emitting radio waves, particularly near us. We've been looking for a while, and that probably means that the nearest sophisticated alien civilisation could be hundreds of light years away. So, even traveling at the speed of light, they take centuries to get here. So, how should I put it? Aliens arriving, demanding to see our leader and up to no good? Probably unlikely. I think if we find evidence for life, it might at first be quite - it might be quite boring. Most of life throughout the Earth's history has been boring.

SC: Speak for yourself, Michael!

MB: Well, yeah. Single-celled organisms are not great to be in a conversation with. T Rex, to be fair, wasn't good at dinner conversation either. So, it's possible that, you know, we might detect the planet, show signatures of life. It might have oxygen and it might have methane as well, which would be an unexpected combination unless there's life there. And we might just see no signs of civilisation from it because it’s got animals, the largest animals it’s got are fish, or the equivalent of fish. Or, you know, it's got dinosaurs or it has a civilisation, but it's not a civilisation that transmits radio waves, a civilisation as of 3000 years ago. There's a lot of life out there potentially, but it might not be necessarily a direct mirror of us or a frightening projection of them.

SC: Would you ever do space travel? Would you sign up to be one of those space holidayers?

MB: Maybe when I was younger, maybe I probably would have. I’m less sure of it now that I've got a family, and it's still a risky venture, definitely. Accidents happen. There was the Virgin Galactic test flight that crashed. Obviously the space shuttle disasters. It is a risky game. Perhaps when I was younger and I used to do things like tandem parachute jumps, maybe I would have leapt at the chance. I'm not sure I would leap at the chance now, maybe I would, but I'm not sure at this this point in my life.

SC: My last question for you is what has been a recent space discovery that you've been really excited about?

MB: Oh, what's been an exciting one? I think I've really enjoyed Comet Neowise, , uh, comment Neo wise, which has been visible in the Northern Hemisphere. I think it's going to fade before it comes to the South, and it's just a beautiful comment, and anyone can see it. It's really accessible. People can take photos off it with their mobile phones, and it's just there, and there have been beautiful pictures of it above Stonehenge, and there’s a photo of it above one of the space X rockets at Cape Canaveral and it's just accessible astronomy. And I think one of the things I like about astronomy as a science and also perhaps beyond the science, is it can be so accessible that there can be a comet and you can look up and see it. And I remember when I first moved back to Australia in 2007 or so and there was a bright comet and I was walking along St Kilda beach and you could point it out to people and go ‘Look, there's a comet’ and it was just, you know, wonderful. And so I think that kind of thing does get me excited about astronomy again. I can get caught up in the minutiae of emails and admin and, editing papers, etcetera, etcetera. But there are these exciting discoveries, and they can be very accessible, and I think that's what gets me excited about astronomy and keeps me connected with astronomy.

SC: It's that undertone of wonder that astronomy in particular seems to facilitate in all of us.

MB: Yeah, I think that's true. And sometimes it can be strangely familiar, that Mars can feel, you see the photos of Mars and it can seem different, but familiar, and that makes it tangible. And the fact that you could look up and see it and that makes it tangible and then occasionally that you know, it's completely bizarre and different. That could make it, it could put the sense that we are unique, that our planet is very unique. And I think that makes a connection with people that some other sciences don't have that kind of opportunity.

SC : Michael, paint us a picture. Imagine tomorrow every leader of every country around the world Russia, Australia, China, the US, everywhere they all announced that due to Covid all funding to all space exploration has to stop, private and public. We just don't have the time or the money for it. What would happen to the world a year from now? 10 years from now?

MB: So I think, um, a year from now, 10 years from now, I think it's really significant. There's a lot of stuff in space that informs us on a sort of grand scale and also on a much more mundane scale. The grand scale stuff, you know, life on Mars, the origin of the universe, that kind of stuff would be curtailed. A lot of our increasing understanding of physics would be curtailed as well. There's new physics that was discovered using, or leveraging off space exploration, you know, [inaudible] Nobel prizes are an example of that. I think on the more practical level it would limit our ability to know about the earth. You sort of flag that as a sort of hypothetical. But there are politicians in United States who want to reduce the amount of money that's available to NASA for their fencing missions, and what that is about is to try and reduce the amount of data that we have available on climate change. They really do not want NASA to be producing more data showing that climate change is occurring. The rate of climate change, the impacts of climate change and so there is a deliberate desire there for ignorance. And I think if we curtail space exploration, there would be ignorance, we would be limiting our knowledge and that would ultimately put us at risk.

SC: Associate Professor Michael Brown . This was very exciting, A bit terrifying. I'm glad to hear we've still got a billion years before we need to sort out the sun, but thank you so much for your time.

MB: It’s been a pleasure.

SC: That was a fascinating discussion. More information on what we talked about today can be found in the show notes. Next time we'll talk to an astrophysicist about life on Mars and how it might be the key to a better life on Earth, architects learning to design in space and Australia's very own rocket man. See you then.

Listen to more What Happens Next? podcast episodes