The eight-hour day. The secret ballot. Universal suffrage. A society that places the common good above individual achievement. How did modern Australia come to be?

Convicts aren’t often celebrated for their contribution to the nation’s progressive political traditions, and that’s something Associate Professor Tony Moore, Monash historian and head of Communications and Media Studies, is trying to change. He argues that the Australian story is more interesting, more inspiring and more surprising than the history we learn at school.

As a teenager, he remembers thinking Australian history was “parochial and tedious” with its “focus on the gold rush or explorers”.

We’re generally not taught how Australia formed part of “a global system of imperialism, where the dispossessed in the United Kingdom were ensnared by the criminal system and transported as forced convict labour to develop colonies”, he says.

The British Empire, with the assistance of merchant ships and the Royal Navy, facilitated “a global movement of unfree workers, together with administrators who moved across colonies forming an imperial ruling class”, he says. Many of those who were sent to Australia represent “the discontents of that ruling class, people who were protesting and agitating for democracy”.

"We achieved democratic constitutions in advance of the UK in the 19th century, and we don't even celebrate or understand that. Why?"

In 1788, when the First Fleet arrived at Sydney Cove, five years had passed since Britain lost the American War of Independence, and with it the right to send prisoners across the Atlantic. One year later, the people of Paris stormed the Bastille, marking the beginning of the French Revolution. And in 1792, the new French Republic declared war on Britain.

One reason Britain didn’t experience a political revolution of its own “is because they exported their political activists to Australia”, Dr Moore says. Transportation to a distant continent was almost as frightening as a death sentence – and in some cases did end in death due to privations in the colonies.

“One line says we achieved democracy because of Federation or because we defended it in the First World War,” Dr Moore says. “Yes, those things did protect it or advance it, but we achieved democratic constitutions in advance of the UK in the 19th century, and we don't even celebrate or understand that. Why? Why did Australia lead the world? One of the least-free jurisdictions on the planet become quite free and quite democratic in the late 1850s and 1860s.”

The forgotten political convicts

Instead of celebrating the bravery and resilience of the political convicts, Australia has largely forgotten them. “There was a turning in the '70s when having a convict ancestor wasn’t considered a bad thing,” Dr Moore says. “There was a reclaiming of that heritage. But, with a few exceptions, they didn't take it any further.”

In 2010, Professor Moore published his book Death or Liberty, describing our debt to the political convicts. About one in 45 of the 164,000 prisoners sent to Australia (about 3600 people) were citizens whose quest for political liberty in their homeland was considered deeply threatening to the status quo.

They included Chartists, a working-class political reform movement in England that existed between the late 1830s and 1857. The Chartists are considered a failed movement in their home country, but their program lived on in Australia, which was one of the first nations to introduce the secret ballot, and was an early adopter of manhood suffrage and payment for members of parliament – all Chartist demands.

William Cuffay was one of them. He was sentenced to 21 years in Australia, after being accused of “conspiring to levy a war” against Queen Victoria (he pleaded not guilty). His political activities in England included campaigning for an eight-hour day.

The son of a West Indian slave and an English woman, Cuffay gained his freedom in Tasmania after three years in the penal system. He stayed on the island, where he worked as a tailor and as an influential union official who led the successful campaign to reform the punitive Masters and Servants Act, dying in poverty in 1870.

At the time of his death, obituaries celebrating his achievements were published around the nation. They included a call for a Cuffay memorial to be built in Hobart – a call that continues today.

Other transported political prisoners included more than 2000 Irish revolutionaries and resistors – who called for their followers to join them in Australia – and Canadians protesting against British rule (they have their monument at Canada Bay, NSW).

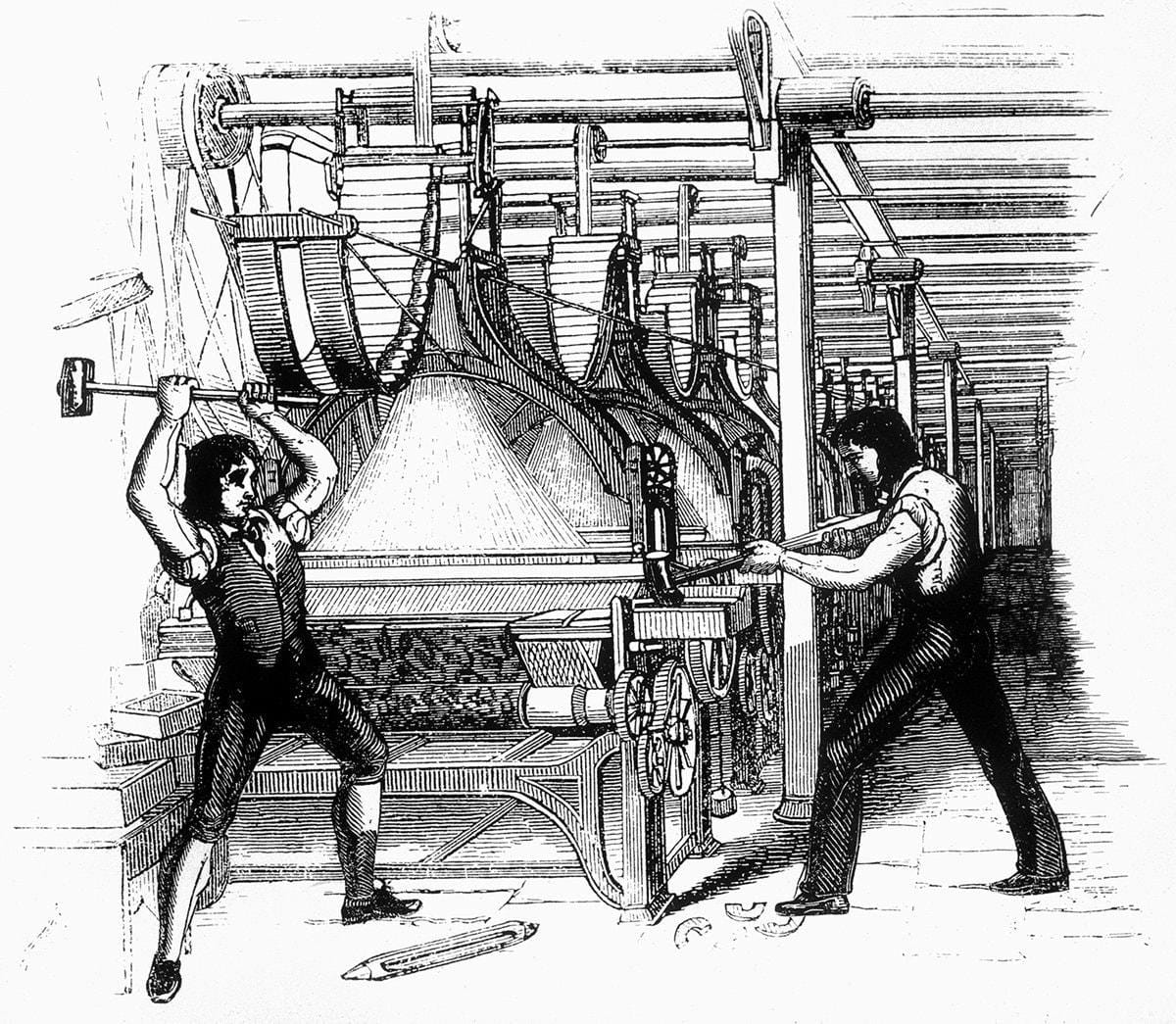

Britain also exported prisoners who opposed privatisation and the new machine age. Among them were the Luddites, textile workers who broke machinery and burned mills to protest against factory wages and conditions; the Tolpuddle Martyrs, agricultural workers transported for demonstrating against a fall in wages; and the Swing Rioters, agricultural workers who destroyed threshing machines in southern England.

In England and Wales, rural workers were disenfranchised by the loss of the commons – land traditionally used for hunting, fishing and foraging. Between 1604 and 1914, successive enclosure acts saw wealthy landowners acquire some 2.8 million hectares.

Dr Moore says the injustice was passed on and amplified in Australia when early settlers – including some serving and pardoned convicts – forcibly acquired land that had been held in common by Indigenous people. Indigenous resistance to British occupation led to both brutal reprisals and massacres by the colonists, and also their detention as political prisoners in their own land. They joined Indigenous resistance fighters from New Zealand and the Cape colony who were transported to Australia.

Dr Moore has received an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant of $757,205, together with cash contributions from industry partners of $310,000, to raise awareness of our convict legacy. The work partly involves coding, analysing and visualising recently digitised convict archives.

Convict records now separated in national collections will be connected for the first time via an open-access online hub. The digital archive will also help historians gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which the convicts resisted their servitude.

“The convict records in Australia are the most detailed, complex records of ordinary people up to that time,” he says. “It's the beginning of modern bureaucracy. Australia was at the cutting edge of keeping files on people. There's court files for when they leave the UK, or Ireland, and there are files here including conduct registers of what happens to them in Australia.”

Even from the earliest days in the colony, convicts went on strike for better wages and conditions, he says. Research from Professor Michael Quinlan from the University of NSW shows that convicts were forming “embryonic, primitive trade unions” in the early 19th century.

Many convicts worked on government farms, growing food for the new settlement. Others were assigned to land owners. If a convict refused to work, this was recorded as an individual act of disobedience. But an analysis of the digital record reveals “patterns of collective resistance”, Dr Moore says. He also wants to trace convict escapes – another form of protest – to see if prisoner strategies can be discerned.

Death or Liberty was made into a documentary for ABC-TV in 2015. Dr Moore hopes to spread the convict story more widely with this project. One hundred micro documentaries telling individual convict stories will be made, ready for viewing on mobile phones. Musicians Billy Bragg, Mick Thomas and Lisa O’Neill will contribute original songs. A travelling exhibition celebrating Australia’s political convicts beginning at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, crossing the country and moving to the UK and Ireland, is also in the works.

Delving into activist media

As a media scholar, Dr Moore will be investigating the innovative media used by many of the activists in their home countries and in Australia – journalism, songs, pamphlets, novels, memoirs, poems, cartoons, posters and banners. Monash SensiLab professors Jon McCormack and Kim Mariott will help bring the project to life.

Dr Moore’s belief is that our convict legacy has much to teach us in this political moment – when almost 2.5 million Australians are employed as casuals, when unions are under attack from politicians and some businesses, when housing is unaffordable for many, and when citizens’ rights are being eroded in the name of national security.

“Australians need to understand how we got to the world our parents were in and we're in, to know what they're defending and how to defend it,” he says. “There are important lessons about being citizens that I think we can learn from these brave people.”