Disinformation is a problem that has over recent decades grown to pandemic proportions, with damaging social impacts on a global scale.

It’s become the tool of choice not only for governments hostile to democracy, but is increasingly employed in domestic politics and for the promotion of toxic ideological agendas.

Disinformation is used to fracture existing beliefs, and to implant false beliefs, seducing its victims to serve the agenda of the player who produced it. Its explosive growth over the past three decades directly follows the growth of digital networks and now ubiquitous social media.

There’s no novelty in the mass distribution of disinformation to promote political and ideological agendas. The advent of Gutenberg’s printing press almost six centuries ago resulted in its large-scale exploitation for the distribution of propaganda.

Less well-known is that one of the first uses of television 90 years ago was for the broadcast of toxic Nazi propaganda.

History shows that newer and faster media for the distribution of information will be exploited for purposes both good and bad.

For purveyors of disinformation, be they rogue states, political groups, ideological movements, or activists promoting malign or dubious causes, the digital age has created unprecedented opportunities.

Ubiquitous access to fast networks via smartphones, and household and workplace computers, permits direct distribution to audiences on the scale of billions.

Advancing digital technologies such as AI permit “microtargeting” with individually customised narratives, and production of convincing “deepfakes” to seduce audiences – my prediction of the impending “deepfake” problem in a conference paper 25 years ago went unheeded.

While deception has been well-studied in the humanities, scientific study of the problem has lagged. Robust mathematical models for deception only appeared 25 years ago, and are not widely known.

Understanding disinformation and deception

Disinformation is an instance of deception framed within a social context, and is frequently associated with governments and political discourse.

While the term “misinformation” is often used instead, current literature usually identifies disinformation as intentional deception, while misinformation is incidental or accidental. Both or either are often labelled as “fake news”.

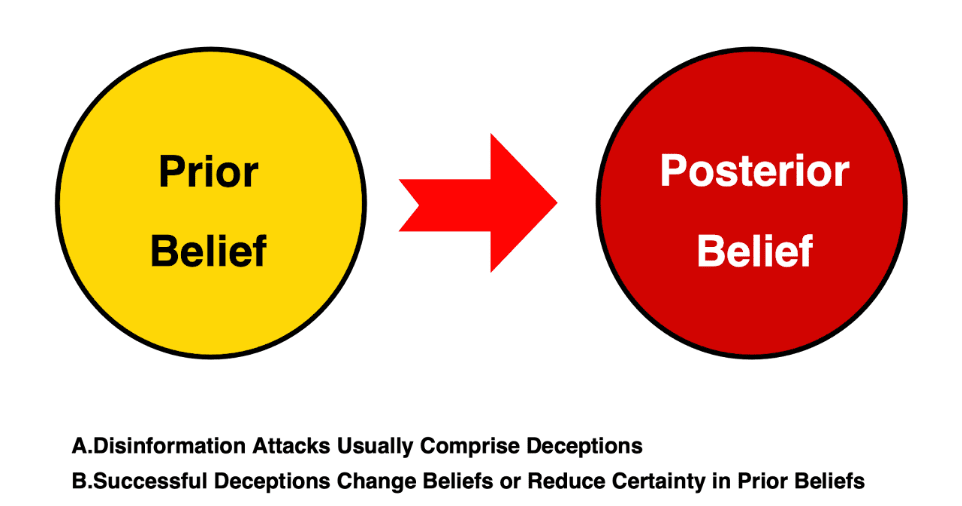

Deception is about changing beliefs – either eroding confidence in an existing belief, or replacing it with a new belief.

Formally: “We define a deception as an action, or an intentional inaction, that aims to bring a second party to a false belief state, or to maintain a false belief state. The intent of a party producing a deception may or may not be to disadvantage the deceived party.”

Disinformation is used to fracture existing beliefs, and to implant false beliefs, seducing its victims to serve the agenda of the player who produced it. Image: Author provided

While deception is often thought to be unique to social systems, its origins are in biology as an evolved survival tool, to aid both prey and predators.

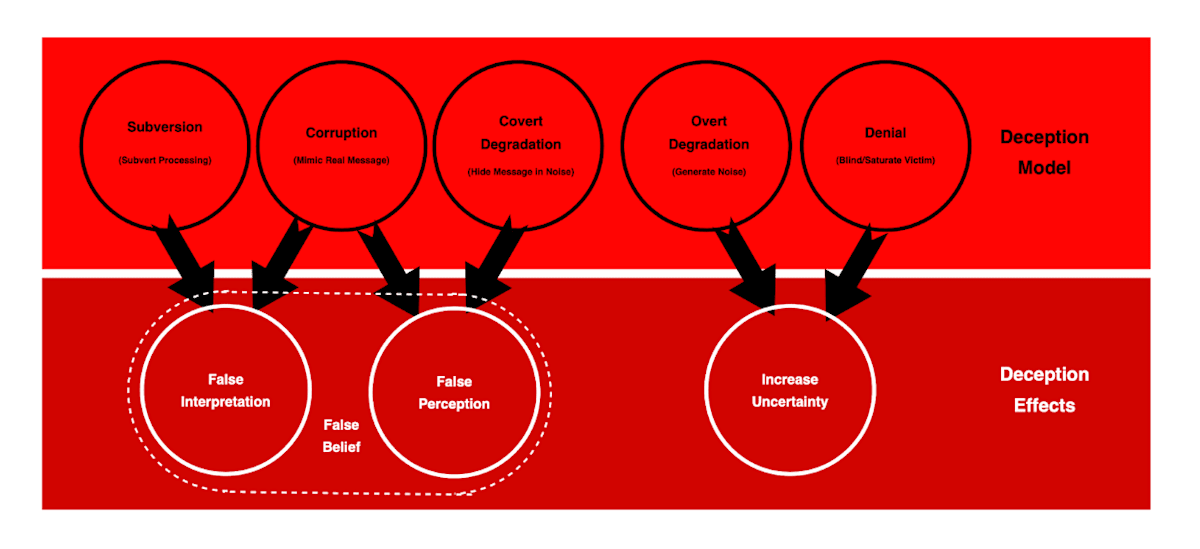

The simplest mathematical model that accurately captures deception is the Borden-Kopp model, developed 25 years ago independently by mathematician Andrew Borden and myself, published one month apart. This model is based on Shannon’s information theory.

This model describes four different ways in which deceptions can be carried out, noting that in practice we often see compound deceptions, where several of these methods are combined to deceive the victim.

Degradation of information is based on hiding a fact by burying in a background signal or noise. In biology it’s exemplified by camouflage and concealment.

There are two possible effects – the victim of the deception may become uncertain of reality, or believe that nothing is present if the concealment is highly effective.

Contemporary flooding of audiences with irrelevant messages to distract from real messages is a good example.

Corruption of information is based on mimicry, where a fake is made to appear sufficiently similar to something real, that the victim is tricked into a false belief. In biology it’s exemplified by mimics, such as moths that appear to be dangerous wasps.

Contemporary “deepfakes” are a good example of corruption.

Denial of information is based on rendering the channel carrying information unusable, temporarily or permanently. Good examples in biology are squid squirting ink to blind predators, or skunks squirting smelly fluids to disable a predator’s sense of smell.

Contemporary examples are “deplatforming” an influencer or blocking a website.

Subversion is the cleverest deception, in which the victim’s processing of information is manipulated to advantage the attacker. While this may involve altering the victim’s goals or agendas, more commonly it involves altering how the victim interprets a situation or fact.

In biology, the best examples are cuckoo species that trick others into feeding them. The best contemporary example is Bernays’ “spin doctoring” in political discourse, where the audience is encouraged to re-interpret unwanted realities as something less odious.

Because the model is based largely on Shannon’s information theory, it is completely general, and this is apparent from testing it against a vast number of real world examples in biology, social systems, and machine systems.

Examples in politics and marketing show this very clearly. The models have been used in simulations to accurately reproduce deception behaviours.

While information theoretic models can accurately reproduce deceptions, their use can be challenging as the mechanisms used to form and alter beliefs can be difficult to describe in math.

The impact of dysfunctional cognition

Why are some people more vulnerable to deceptions than others? This depends on how individuals process what they perceive.

Individuals who are naturally sceptical, and critically assess what they observe, can often unmask deceptions and reject them. Naive individuals are vulnerable to deception ,as they are either unable or unwilling to critically assess their observations.

Human cognition is an evolved survival aid, and evolution often favours solutions that minimise both effort and reaction times. The result is the frequent use of shortcuts in processing perceptions, usually at the expense of accuracy. The adage of “near enough is good enough” often applies, and skilled deceivers know how to exploit this vulnerability.

Common cognitive vulnerabilities include confirmation bias, its sibling motivated cognition, the Dunning-Kruger effect, and a wide range of identified cognitive biases, many of which are instances of the preceding vulnerabilities.

The spreading of disinformation

The problem of why deceptive messages spread well has been studied extensively.

One identified cause is because deceptive messages can be crafted to seduce audiences with known cognitive biases, a technique widely used in politically polarised media, social media, and fact checking. This taps into confirmation bias and motivated cognition. Truthful messages are usually much less enticing than fakes.

The other identified cause is the behaviour of social networks, especially when connected by pervasive high-bandwidth digital networks.

Analysis of vast amounts of traffic on social media platforms, and extensive simulation modelling, has found that most often deceptive messages spread in a manner well-described by the mathematical models used by epidemiologists in medicine. Social media “influencers” are often “superspreaders” of disinformation.

The scientific study of how disinformation works, how it seduces its victims, and how it spreads, is gathering momentum, after decades of being largely ignored. As with many areas of science, the best is yet to come.