Men dominate the upper tiers of publishing, but it’s women who are more likely to write and edit books, often for meagre financial reward.

Women also write more books than men, yet it remains easier for male authors to be published, and once published, men are more likely to be reviewed.

Monash’s Associate Professor Simone Murray has spent her academic career studying the evolving business of books.

She first began examining the relationship between women and books in 1995, when she left Australia for England to start a three-year PhD at University College London about feminism and the book industry.

Virago Press, a British publisher devoted to women’s writing, sparked her interest in what she calls the “sociology” of books. Virago began in the 1970s, and has published influential feminist authors of fiction and non-fiction including Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter and Tillie Olsen.

Just as importantly, it republishes once celebrated women writers who may have fallen out of contemporary favour, including Christina Stead, Vera Brittain and Rebecca West.

“I became aware of Virago when I studied for my undergraduate degree,” Dr Murray says, “but we only ever talked about the contents of the book. We never talked about how these books came to be and how they’d been rediscovered, and what the effect of that was. So, I got interested in looking at literary studies beyond the words on the page that would start to ask, who produces these books? How do they circulate? Who reads them? How do they get read?”

"Women have been published, but the terms on which they've been published and the numbers who have been published, the ways in which they've been reviewed and the ways they're forgotten, really aren't equal with males.”

When Virago began, some people said a feminist publishing house was not necessary because “writing’s about the only art form in which women can claim a long history, from Austen and the Brontes and George Eliot, and so on”.

“But as the founders of Virago pointed out, women have been published, but the terms on which they've been published and the numbers who have been published, the ways in which they've been reviewed and the ways they're forgotten, really aren't equal with males.”

Since 2010, volunteers across the US have tracked how male and female authors are treated by the literary press in the Vida Count, an annual snapshot of book reviewing practices.

“The volume of women getting reviewed is around 30 per cent of the total coverage,” Dr Murray says. “And so, they use this statistical evidence to make the case that women are published in great numbers, and have been for a long time. But once they’re in a literary system, their work is very often sidelined or reviewed in a dismissive way, or given a capsule review of 100 words, whereas someone else gets the featured review on the front page.

“And every year they bring out the accounts with the little blue and red pie charts. And every year the literary editors of journals smack their foreheads in horror and go, ‘This can't be true’. But it’s actually hard for them to argue with the numbers.”

Untimely beginnings

Dr Murray says 1995 was “probably the worst time to start a PhD about the book industry, because it was the absolute peak of fear around the future of the book”.

“There were umpteen academic conferences and journal special issues talking about the way that digital was going to eclipse print, and that the book was on the way out.”

That same year, feminist author Dale Spender, an Australian who had been living in London, published a book called Nattering on the Net. In the book, “she makes that case that we should chuck books. It's a superseded medium, there's no point in women getting in on that medium given its time has passed; we need to get in on the digital”.

Spender’s predictions about the death of books haven’t come to pass, although the industry has had to make difficult adjustments, with the “bricks and mortar” retail sector facing stiff competition from online sales and the digital market, and smaller publishers finding it harder to survive.

“After the Kindle came out, there was a dip in hardback and paperback sales,” Dr Murray says. “But that's actually started to plateau, and now e-books are really big in genre fiction categories like romance, particularly paranormal romance and horror. But literary fiction and non-fiction are actually seeing a resurgence in print sales.”

The reasons are many, she says. We like to hold the books we love, to return to them, to mark favourite passages, to see them on our shelves – an eBook purchase confers a non-transferrable licence, not ownership of the book. Also, “we have enough screen time”, Dr Murray says. “The last thing some people want to do late at night is get a whole blast of blue light that messes with your sleep patterns while you're sitting in bed.

“In fact, there's this movement now, called the 'slow reading movement'. It's big in New Zealand, and also in San Francisco. People convene in a bar or a restaurant, and then they talk for about 20 minutes. And then, everyone brings their book, and then they sit in a back room and no one talks for an hour. It's understood that they're not being antisocial. All devices have to go off. It's almost like a meditation practice.”

A false division

These days, print versus digital is a false dichotomy, Dr Murray says. Readers, writers and the industry have all found ways to interact with books online. (She’s written about this phenomenon in The Digital Literary Sphere: Reading, Writing, and Selling Books in the Internet Era.) Book clubs, author blogs and online book reviews all thrive on the internet. And many authors have social media accounts, in which they communicate directly with their readers.

Writers’ festivals have become more popular, too, and offer opportunities for live-streaming, live-tweeting and Instagram shares. The contemporary literary scene favours writers who are comfortable performing before an audience and sharing on Facebook, but can be brutal for more introverted personalities – an author’s social media presence can even influence whether a publisher is prepared to take them on.

Dr Murray has worked in publishing as well as academia. She was at HarperCollins just before the Lord of the Rings trilogy became a movie franchise, while the publisher was bracing itself for the bonanza that duly came.

This led her to investigate why big media companies were buying publishing houses (and to write The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation). She argues that for these companies, books have value in “the same way that cutting-edge fashion designers see their runway shows as a kind of loss leader for their other markets”. Publishing is their “research and development arm where they do their big ideas. And things that prove popular can then be leveraged to create a whole raft of products which will cross-promote each other.”

Book clubs and loyalty

In this diverse and changing landscape, why do women continue to be so loyal to books? “That’s a huge question,” Dr Murray says. “I think women have often looked to books as a way of role-modelling potential ways of being in the world.” She cites the phenomenon of book clubs, in which women gather to discuss books they select together. “They facilitate an idea of sociability around books, of empathetic engagement.”

Books also allow women writers to put some distance between themselves and their creative identity – to some extent, it’s still possible for an author hide behind their book.

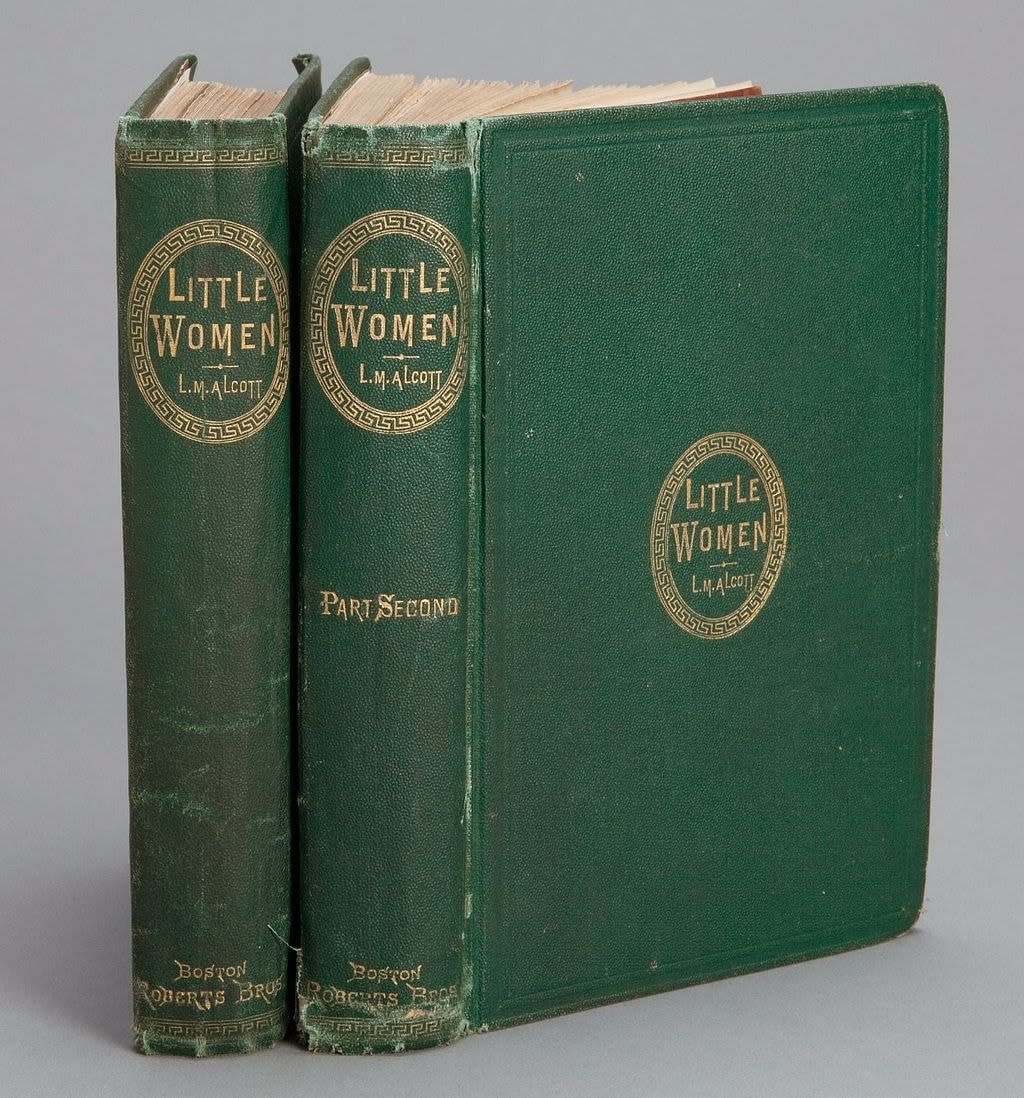

In a book, a woman can describe the world as they understand it and as they want it to be. The limits of both are explored in Greta Gerwig’s acclaimed film adaptation of Little Women. The writer-director drew on Louisa May Alcott’s personal letters and diaries to frame her screenplay about the four sisters in 19th-century Massachusetts.

Alcott’s publisher told her no one would buy her book if Jo (Alcott’s alter ego) did not marry by the end. And so Alcott, who remained unmarried in life, duly invented a suitable husband for Jo, although in her book she denied her readers the sentimental satisfaction of seeing Jo married to Laurie, the boy next door.

The final scene in Gerwig’s movie is not Jo’s marriage, but the printing of Little Women itself. She shows the book on the press, how the pages were sewn together, and how the title was embossed in gold foil.

Finally, we see Jo (played by Saorise Ronan) clasping the completed book. Dr Murray says her expression – intense pride, followed by apprehension – is how many women authors still feel when they publish their book and realise that they cannot control how the world will receive it.