If slang is the people’s poetry, then Australia lost a poet last week.

Barry Humphries breathed life into Australia’s “slanguage” – but it was often an imagined life. When it comes to their lexicon, Australians take pride in skirting the thin line between reality, romanticisation, and furphies.

Humphries took linguistic invention to extremes – plucking words and phrases out of obscurity, but also pushing or exceeding acceptability.

In this way, Humphries joined others who have guided Australia into a sense of nationhood by contributing words, attitudes and a few porkies to our national lexicon.

‘Slangy philosophers’ in Australian history

Slangy philosophers emerge at Australia’s key points, and elevate certain words, phrases and verse to help us make sense of our national experience.

In his 1898 dictionary, E.E. Morris famously noted the impoverished state of “Austral English”: “There never was an instance in history when so many new names were needed, and there never will be such an occasion again.”

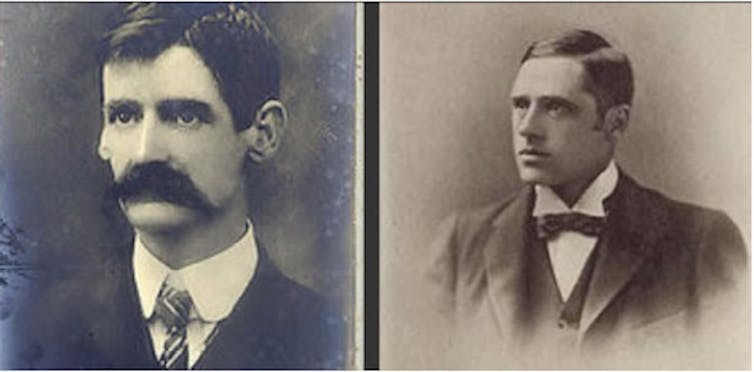

Australia’s slangy philosophers have historically risen to the occasion. Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson wrote on topics of billies boiling, mateship, and waltzing Matilda. However, they didn’t always agree on whether and to what degree the bush should or might be romanticised.

Lawson was perhaps the less sentimental of the pair, writing in his poem The City Bushman (1892):

“Don’t you fancy that the poets better give the bush a rest, Ere they raise a just rebellion in the over-written west?”

A certain romanticisation of Australian ways of speaking, and disagreement about those ways of speaking, seem to be part of Australia’s linguistic landscape. During a great period of Australian myth-making (1890-1925), newspapers and magazines such as The Argus, Australian Tit-Bits and The Bulletin enabled the public to write letters or stories and debate one another.

Readers aggressively debated Australian word etymologies – and the degree to which these words were or were not Australian. For instance, a Bulletin writer by the name of “Blue Duck” dismissed the emerging Australian slang, writing, “Much Australian slang is simply cockney flash, introduced every mailboat by stewards.”

While Mr. B. Duck might be overstating the case, his comment hints at a wider truth. Many aspects of the Australian lexicon first emerge in Britain, or in the imaginations of our middle-class citizens or artists.

For instance, C.J. Dennis’s fictional larrikin Ginger Mick – one of Australia’s original slangy philosophers – had a style of speaking that was more a middle-class flight of fancy; some argue more cockney than Australian.

But Mick’s imagined ways of speaking became loved by Australians, and played a role in our emerging nationhood. We might argue that Barry Humphries and Bazza McKenzie did the same, albeit in a different era.

Humphries and the lexicon of New Nationalism

Barry Humphries’ Bazza McKenzie character emerged during Australia’s New Nationalism in the 1960s and ’70s. In linguistic terms, this was an era of growing colloquiality in Australian English.

Linguists Peter Collins and Xinyue Yao linked the identifiable rise in Australian colloquialisms from 1961-1991 to:

“... an upsurge of nationalistic fervour in Australia at this time, epitomised most colourfully and infamously in the cult of “Ockerdom” of the 1970s, and heralding the decline of Britishness in Australia.”

In other words, while Australians have long been noted to speak more colloquially than their American and British counterparts, this bloomed during the era of New Nationalism – and shows little signs of stopping.

Bazza McKenzie – in the British magazine Private Eye – leaned into the Ockerdom of the era. Humphries noted that:

“... words like cobber and bonzer still intrude as a sop to Pommy readers, though such words are seldom, if ever, used in present-day Australia.”

However, Bazza might have thrown such words a lifeline. Humphries took pride in giving old Aussie words and phrases a second life, drawing inspiration from school days, public life, or friends like “Shearing Bill, who had spent most of his life in the outback […] collecting arcane vernacular”.

In 1965, Humphries noted he’d first heard chunder in Victoria’s elite private schools 10 years earlier (though it was already being used “by the Surfies, a repellent breed of sunbronzed hedonists […]”). When it hit the big screen chunderama-style, it was Bazza who popularised its (probably false) origin story, the nautical warning for others to “watch under” – successful slang is usually buttressed by tall etymological tales.

Bazza, taboo and the Australian lexicon

Of course, Humphries – especially through Bazza McKenzie – didn’t just breath life into old Australian words, but coined many of his own.

Slang generally flourishes wherever things go bump in the night, and Humphries had in his sights Victorian taboos regarding body parts and bodily effluvia. These taboos guided our public imagination (or euphemism) at least into the 1980s, and for some beyond.

Humphries coined or popularised cheeky ways to discuss vomiting (for example, technicolour yawn, liquid laugh (down the great white telephone)), urinating (such as drain the dragon, point Percy at the porcelain), and masturbation (flog the lizard, jerking the gherkin). He was also a master of the frankenphrase – pulling together bits and pieces of the Australian lexicon, and reinventing them.

Read more: ‘No worries’ looks to be a simple little expression – but it’s anything but

Through Bazza, Humphries took phrases based on ugly as […] to new levels, popularising a shift away from religious connotations of “ugly” (such as ugly as the devil, ugly as sin) toward containers and orifices as the standard of comparison (for example, ugly as a hatful of arseholes) – in Australia at least.

In some cases, Humphries went too far, especially for modern sensibilities – his character Sir Les Patterson deliberately sought to offend. Humphries popularised more than a few pejorative terms for marginalised people – words that we won’t repeat here.

Beer-swilling Bazza and our slang from ‘Down Under’

Not only did Humphries change Aussie slang, he changed the way we thought about it. Colin Hay cites the influence of Bazza McKenzie on Men at Work’s iconic song Down Under:

“He’s a master of comedy, and he had a lot of expressions that we grew up listening to and emulating. The verses were very much inspired by a character he had called Barry McKenzie, who was a beer-swilling Australian who travelled to England – a very larger-than-life character.”

To survive, slang expressions require what Ben Zimmer once described as a “perfect lexicographical storm”. We think there are usually four things that create this storm, and successful Bazza-isms have them all – celebrity endorsement, handiness, imagination, and a magic furphy or two.

Sure, Bazza’s wondrous contributions may not be part of most people’s active vocab, but they do belong to a kind of (national) lexical Wunderkammer – loved, admired and trotted out as stellar examples of Australian slang.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.