What can you do with 99 seconds? Check your email? Fire off a tweet? Walk 100 metres?

For current men’s marathon world record-holder, Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge, 99 seconds is all that stands between him and the sub-two-hour (or “sub-2”) marathon run.

Breaking the two-hour barrier in the men’s marathon could be the defining moment of Kipchoge’s illustrious career, if he can achieve it.

Read more: Five tips to help your kid succeed in sport – or maybe just enjoy it

But how close is he? How hard is dropping 99 seconds, really?

To find out, in a study published today in Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise, I crunched the data on all male and female marathon world record times since 1950.

The barrier broken

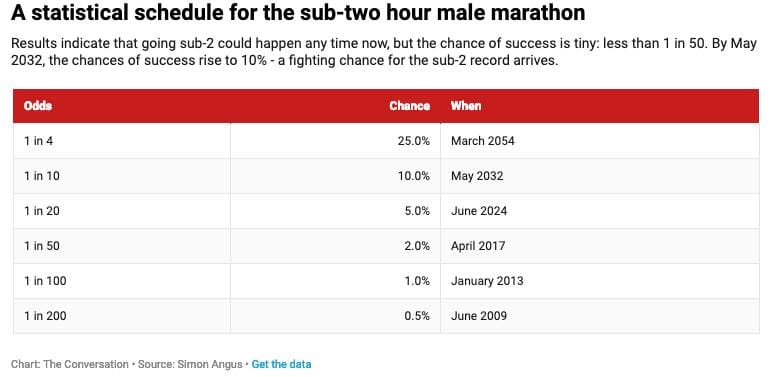

Kipchoge could break the sub-2 barrier tomorrow, but it's very, very unlikely – there’s just a 2 per cent chance of it ever happening, to be precise.

The more likely answer is that we'll have to wait until May 2032 to see someone – most likely not Kipchoge – go sub-2 in an official event. By that time, the chance of someone going sub-2 increases to 10 per cent.

But we may have to be even more patient – 2054 sees the probability of a sub-2 marathon rising to 25 per cent.

The reason for the shifting date is that from the standpoint of statistics, there's a direct connection between the predicted date of arrival of the sub-2 moment, and its probability of happening.

The key insight of the approach comes down to the difference between what's likely to happen on average, and what's likely to happen in just one single realisation of the future.

The Bradman average

Take Australian cricketing legend Don Bradman’s phenomenal test batting average of 99.94 runs. This number represents the average over Bradman’s 80 innings (including 10 not-outs).

But what we should remember is that, when using this average to predict the future, the average has some variation associated with it. So actually, we should probably quote the Don’s average as 99.94, within the range 71.0 to 128.8.

What these numbers mean is that if Bradman were to have played another 10 test innings, then the average of those 10 innings would lie, with 95 per cent chance, within the range 71.0 to 128.8. (For the statistician in all of us, yes, that’s a confidence interval.)

Which is helpful. But what if the English skipper who faced Bradman, Norman Yardley, is playing one of those fictional next games? He cares more about what Bradman might score right now, at the crease, not over a series of 10 such events.

At this point, Yardley needs what's called a “prediction interval” – the likely range of a single inning’s score (not the average over a number of innings).

Sorry Yardley. The answer is a tad demoralising – the prediction interval for Bradman’s test innings is from 0 to 343.5 runs!

In other words, with 95 per cent likelihood, a single Bradman innings will fall anywhere in the interval 0 to 343.5 runs.

A marathon prediction

Back to the marathon. It's exactly this insight that helps us to make a more accurate point-prediction for when the sub-2 marathon will be run, leading to our May 2032 estimate (with 10 per cent likelihood).

The neat thing about the modelling framework is that we can also calculate the likely fastest ever men’s marathon time, again at 10 per cent likelihood. That comes in at 1:58:05, a prediction that turns out to be remarkably close (within seven seconds) to one made on entirely physiological grounds in 1991.

Importantly, we can also explore female marathon times in the same way.

For instance, in the analysis, the likely fastest ever women’s marathon time equates to 2:05:31, about 10 minutes faster than the current world record, set in 2003, of Paula Radcliffe (UK).

But what time target would be the equivalent for women of the men’s sub-2?

Knowing the limits of male performance, we can simply calculate the distance from the male limiting time (1:58:05) to the two-hour time, a difference of one minute, 55 seconds.

We can then express this difference as a percentage of the male limiting time, giving 1.62 per cent, and add it to the female limiting time. This procedure gives us a time that is the same distance, in performance terms, from the female limiting time as the sub-2 barrier is from the men’s.

The result is 2:07:33 – which doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

The sub-120 and the sub-130

For this reason, I suggest that a reasonable choice for an arbitrary focus for elite female performance could be 130 minutes. Let’s call it the “sub-130-minute marathon”. (Remember, the sub-2 – or sub-120-minute – barrier is itself entirely arbitrary.)

Which leads us to another important observation.

Paula Radcliffe’s remarkable 2:15:25 world record was set one sunny day in London in April 2003 – and here we are, almost 16 years later, and the time still stands.

For context, the male world record mark has been improved on seven times over the same period. So where are all the female world-record marathoners?

Read more: The science of parkour, the sport that seems reckless but takes poise and skill

I don’t have a full answer to that question. But a fascinating study from 2014 of the characteristics of the best male and female marathon runners in recent times gives us an important clue.

While for male marathoners, African runners better their best non-African counterparts to the tune of about 2.5 per cent, for female marathoners, no difference presently exists between African runners and the best of the rest by continent.

It would seem to me that there's likely a group of world-record-smashing African female marathon runners living somewhere on the planet today, but nobody knows who they are. Yet.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.