A public architect designs the spaces that are open to everyone – train stations and libraries, squares and parks, museums and university campuses.

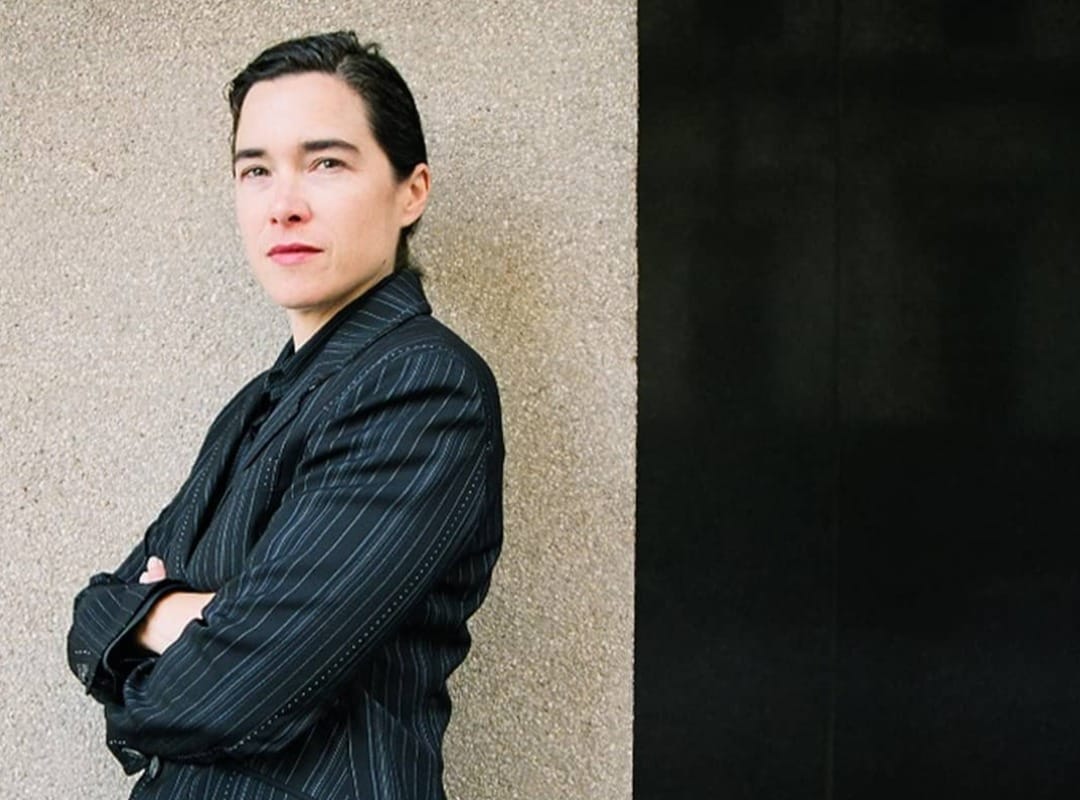

Shelley Penn, who recently became a Member (AM) of the Order of Australia for her services to public architecture, says well-designed public places respect the people who use them, allowing beauty to become part of our daily experience.

Since 2016, she’s also been the Monash University Architect, where her role is not to design, but to advise the University – to help ensure the highest quality is achieved in its campus environments.

Her biggest immediate challenge is supporting the University’s work with the Suburban Rail Loop Authority on the long-awaited Monash rail link at its Clayton campus, with works scheduled to begin in 2022.

The underground station will be on the Normanby Road edge of the campus. It will cater to two cohorts – University students and staff, and also people who live and work nearby, including at the Monash Technology Precinct.

Ideally, the station will be “easy to get to and comfortable and safe, and feel like a positive place to be”, she says.

“It should also create more uplift and economic vibrancy, bringing more people from the community to the north of the campus. It’s a real opportunity for the University to engage and extend its place connections.”

Because people will walk and cycle to the station, she says it’s vital that Normanby Road is also safe, and “that means slowing traffic down”.

“We’re trying to create this sense that there’s not a hard border [with the campus], that it’s permeable and part of the wider community,” she says.

“I know the Uni welcomes people in. We can set a benchmark for the quality of an urban environment that positively affects the surrounding areas.”

A similar opportunity will be created by the Monash-based Victorian Heart Hospital, on the southern side of the campus at Blackburn Road, when it opens next year.

A vision to improve pedestrian access

Adjunct Professor Penn acknowledges that one of the design challenges facing Monash Clayton is the multi-lane roads that border the campus, creating a physical and psychological barrier with the surrounding area.

She says the University is “developing a vision” to improve pedestrian access along and across Blackburn Road, including where the University’s Jock Marshall Reserve wetlands and boardwalk are also located.

Part of Professor Penn’s role involves advising on a refresh of the Monash masterplan, originally devised by architects McGauran Giannini Soon in 2009.

Living, working and having access to well-designed places “makes a huge difference to people’s wellbeing and to social equity, and to our health individually”, she believes.

This means “places that are amenable, that feel safe and inclusive, that are sustainable and easy to use, and, importantly, are fit for purpose; that offer some delight. They’re lovely to be in. They give something to our spirit.”

She became a public architect about 20 years ago after becoming “a little bit disillusioned” with private practice.

A step into public architecture

“I felt like another lovely living room or renovation wasn’t really going to change the world,” she says. “So I stepped away for a while, and that serendipitously led to a role in public architecture in Sydney.”

When the Victorian Government Architect role was created in 2006 with the appointment of John Denton, she was also appointed as the Associate Government Architect.

“We make the case for design quality,” she says. “There tends to be a perception that quality is about the frills and the dispensable stuff that you can take or leave; if you can’t afford [it], you chop it off.”

But she argues that “it doesn't matter how much money you’ve got. The budget is what it is – let's do the best we possibly can within that.”

Read more: Reconciliation through architecture: A chance to build on the past

Government architects are now established in almost all states and territories, she says. The role is similar to that of the Monash architect, but the position isn’t common in universities. “Monash is quite advanced in that regard.”

Australian approaches to procurement have “tended to focus on the bits we can measure, time and money”, yet most people respond to a well-designed built environment, and recognise when quality is absent, she believes.

“We desperately need to densify our city in my view, but there’s a very legitimate fear of development because so much of it is indiscriminate and poorly done.

“On the whole, most people doing development don’t want to create poor outcomes, but they often don’t know how to either invest in it, to get it right, or aren’t skilled to make the judgment that something is not good enough, or can be better, and often we need stronger planning policies that enable authorities to say, ‘That’s not acceptable’.

“And so bad developments go up all the time. No wonder people are unhappy about them. Instinctively, they know they’re horrible, but at the drawing stage or the planning stage, it’s harder to make that judgment, without recognising the value of good design, and the skills needed to get it.”

Which is why architectural advisers can play an important role.

Savouring the ‘landscape as a whole’

She says she doesn’t have a favourite Monash building. “I like to wander, walk around the University,” she says.

She enjoys “the landscape as a whole, with its variations and special places, and many excellent buildings within the landscape” – including the planting of local native species on all the campuses.

“Peninsula campus is actually quite extraordinary,” she says. “The landscape there is very special, but different from the Clayton campus. At Peninsula you can sense that the ocean is not far away. You can see that the soil is sandier, the light is different, so you’ve got a sense of your location.

“That’s a key thing about how Monash manages its campuses – the strong sense of place specificity, which is pretty exceptional.”

In high school she wanted to be a writer, but studied architecture at the advice of her careers guidance counsellor.

“When I was 14 or so, I thought, ‘Imagine if I could write something, and somebody who was blind could read what I’d written and feel the feelings that I’m feeling...Wouldn’t that be a fantastic thing?’

“And with architecture, I remember a shift probably a couple of years into architecture school. I was thinking that if the sun came in the window of someone’s room, and the window was particularly beautiful, the depth of the wall, or whatever it happened to be, that would make you feel a bit better in the morning.

“And if you feel a bit better, you’re more likely to smile or be nice to the next person you bump into. And it’s naive in a way, but I also think it’s not.”

Professor Shelley Penn AM is Adjunct Professor of Architecture Practice at Monash Art, Design and Architecture