We know public transport takes traffic off the road and is better for the environment, but most of us prefer driving to taking the bus.

The director of the Monash Mobility Design Lab, Dr Selby Coxon, believes better design could persuade us to think again. People understand design is important when they choose a vehicle, but don’t appreciate how it contributes to their experience on public transport, he says.

The lab has worked on designs for buses, trams, trains, autonomous vehicles and bicycle paths. “As designers, we want to elevate the experience people have on public transport,” Dr Coxon says.

He’s interested in our reactions to crowding, and how that might affect our willingness to use public transport. Can good design ameliorate the effects of overcrowding? How much of our discomfort is cultural, or connected to the greater degree of amenity we can enjoy in our SUV?

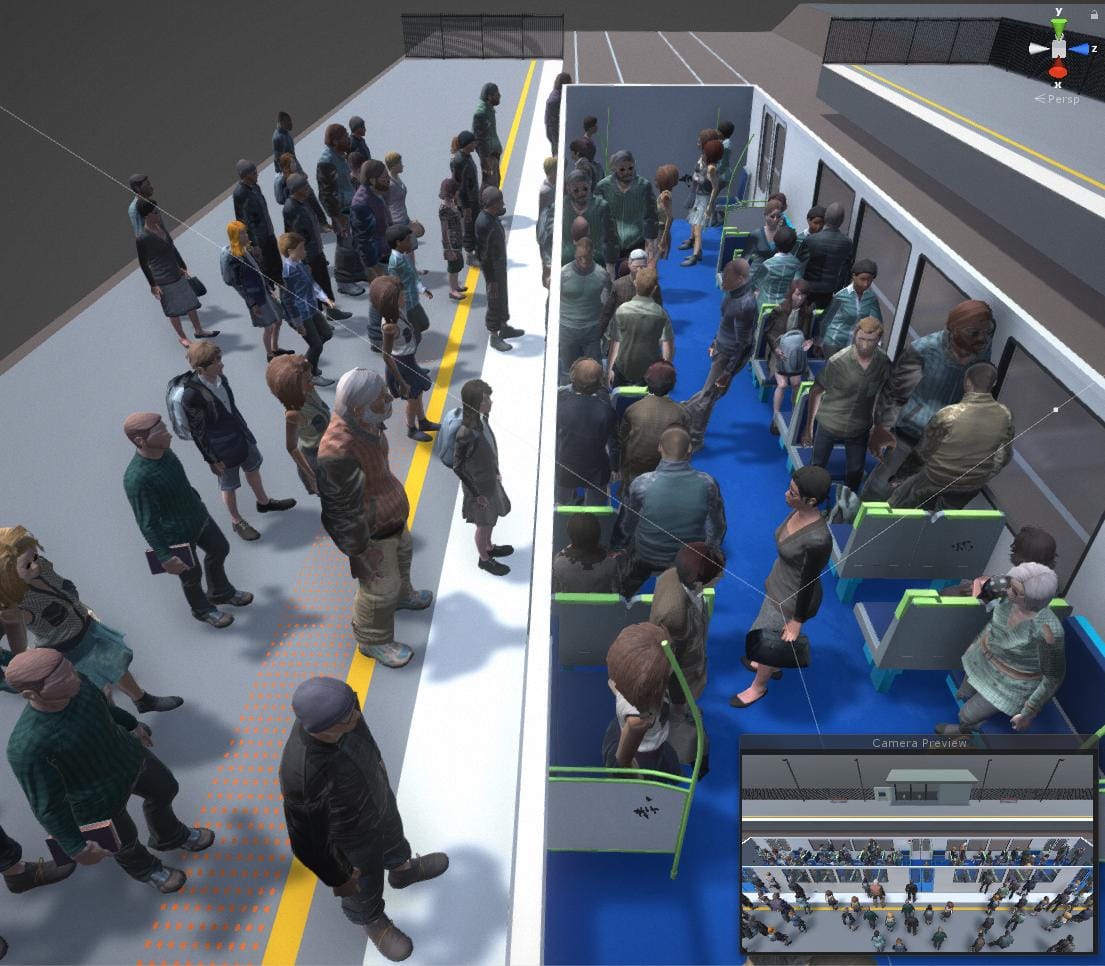

For instance, it’s well-known that trains are becoming more congested, but can train interiors be designed so that people are distributed more optimally throughout the carriage and overcrowding is reduced?

Dr Coxon looked at the issue for his PhD. At the lab he's used computer simulations to see how people would move differently if the doors and seating were configured in new ways.

Accommodating more passengers isn’t simply a matter of taking out the seats, he says.

“People are, understandably perhaps, concerned about being trapped in the middle of a carriage on a crowded train, so that they can’t get off at the stop that they want to. So there is a tendency to crowd into the vestibule area.”

But the design can be tweaked “to support the confidence of the passengers to move further in”.

The Victorian government has ordered new high-capacity trains from China that are designed to carry more passengers. Although their design didn’t come from the Mobility Design Lab studio, “it’s still a space that we work in and we hope to influence”, he says.

Ramping up access for wheelchairs

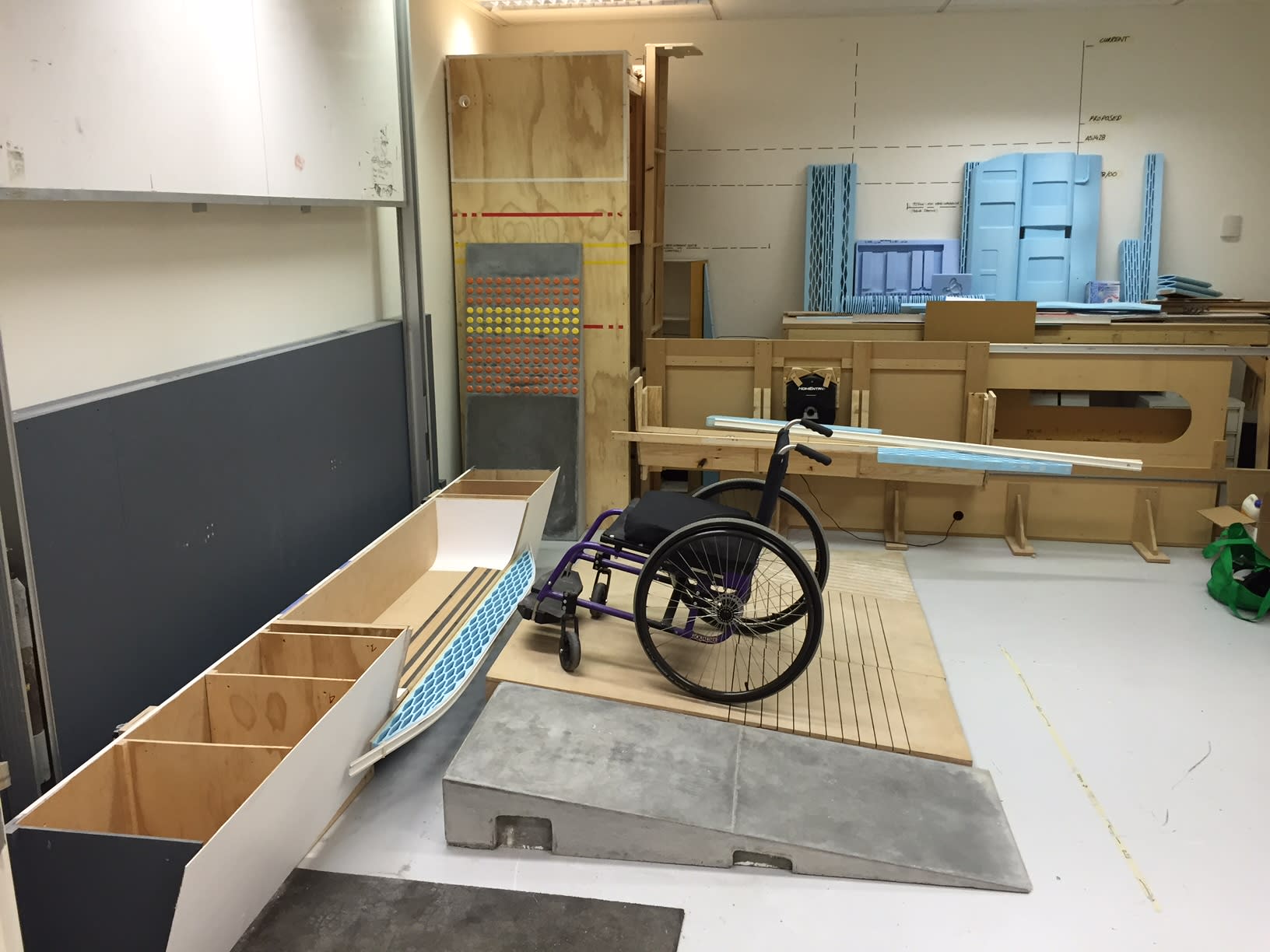

In the meantime, Mobility Design Lab researcher Vincent Moug is investigating how to improve access to trains for people in wheelchairs.

At present, wheelchair-bound passengers on metropolitan trains must position themselves at the end of the platform nearest the train driver so they can be seen when the train comes into the station.

“When the driver sees them, they get out of the train and deploy the ramp,” Dr Coxon explains. “And the disabled person then boards.”

The protocol is time-consuming, disrupts the timetable, and can be stressful for the passenger, who is unable to roll on and off the train without fuss.

Dr Moug’s work, which has industry support, is examining how people in wheelchairs can board and alight from trains without driver assistance.

The research is looking at a design that can close “the gap” between the platform and the train.

“In many respects, boarding and alighting a train across that gap is the ‘holy grail’ of accessibility on trains,” Dr Coxon says. “It’s probably haunted train designers since the first locomotive was rolled out.”

Who goes first?

Outside of the train station, he’s working with Monash intelligent systems engineer Professor Hai Vu, who’s researching autonomous vehicles, particularly how they interact with pedestrians who might cross their path.

At present, foot travellers and drivers communicate wordlessly, assessing whether they’ve been seen and who will give way, usually by means of a nod or small wave. But what happens if you have no driver?

“If a car is pre-programmed to automatically stop the moment a human being comes within a certain distance, then it’s going to take a long time to move along,” Dr Coxon says.

“There has to be some kind of arrangement to enable cars to have priority at certain times, and at other times, at traffic lights, we’re able to then cross into the road. We’re exploring this in a variety of ways and hoping to influence what the rules are going to be in our relationship with these things.”

Dr Coxon is sympathetic to the view of Monash's Professor Graham Currie, director of the Public Transport Research Group, who is sceptical about claims that driverless cars will dominate our roads in the not-too-distant future.

“I think these things are incremental. I suspect that there are benefits to having autonomous vehicles move people around, but they will be in isolated and closed areas.

“We already have examples of that. You can take one in a fun fair or theme park. I imagine the CBD could almost be closed off.”

Trams and driverless transport would be used within certain limits, with normal traffic excluded to outside the border. The design lab’s work on driverless public transport explores this vision.

Dr Coxon doesn’t own a car, but he’s only half-joking when he suggests that walking (or “active transport”) could play a greater role in our transport future.

Flexible work arrangements and better online connections could see even more people staying at home and logging into their virtual office. For these people, a neighbourhood stroll can take on greater importance.

Connecting the dots

Public transport infrastructure (and that includes roads and paths) affects social interactions, too, Dr Coxon says. Are there ways social connections can be strengthened by how our public transport infrastructure is designed?

The Mobility Design Lab also looks at how to improve the experience of cyclists – a particular interest of designer and cyclist Robbie Napper.

Dr Napper is working with the Amy Gillett Foundation to see what can be done to decrease the vulnerability of cyclists to serious injury when cars cross into cycle paths while turning left at intersections.

“Is there a way we can redesign those intersections and junctions to make it easier for the drivers?” Dr Coxon asks. “And for drivers and cyclists to be aware of each other to avoid those collisions?”

New energy sources are also changing public transport design.

The advent of electric buses, for instance, means buses can now be redesigned in positive ways, he says.

“When you have electric motors in the wheels and a different type of energy source, that influences how you can arrange your passengers,” he says. “There’s a better opportunity for level boarding. When passengers are on board, they don’t have to face climbing steps at the back.”

The design lab is now beginning its third year. Dr Coxon says that as far as he knows, the transport expertise gathered at Monash cannot be found elsewhere.

“If you take Graham Currie’s Public Transport Research Group, then there’s Hai Vu’s work on intelligent transport systems, the Monash University Accident Research Centre, the Monash Institute of Rail Technology and then there is us. That grouping is unique.”