The musician Billy Thorpe called Berties the “best live music club Australia has ever had”. This was in the mid-’60s, when Berties was unlicensed and filled with teenagers. The owner, Anthony Knight, sat at the entrance – on the corner of Spring and Flinders streets – dressed in velvet and lace. “Berties was all about local live music, and people came in droves simply because of the bands and the vibe,” Thorpe said.

Melbourne became the centre of Australia’s music scene during the Mod years. Monash urban historian Associate Professor Seamus O’Hanlon says this was partly because Australia’s fashion industry was based in Melbourne and Mods liked to dress well. Another reason was that poker machines had been introduced in Sydney and were replacing live bands. American soldiers on leave from Vietnam also went to the harbour city, which meant “many of the places that had been venues for teenagers were taken over by soldiers”.

Melbourne band The Loved Ones were a fine example of the Mods. “The look was smart, the men were in suits,” Dr O’Hanlon says. The Beatles tour of 1964 inspired The Loved Ones, who had a wilder R&B sound. The Melbourne music scene was tribal – the Rockers versus the Mods – but “one of the unusual things about Melbourne was that the Mods and Rockers liked the same music,” says Dr O’Hanlon, “whereas in England they didn’t and would fight each other everywhere. Here they would go to the same venues.”

Dr O’Hanlon is researching music in Melbourne from the ’60s to the present as part of an Australian Research Council Discovery Project, Interrogating the Music City: Cultural Economy and Popular Music in Melbourne. The project is led by Associate Professor Shane Homan from the Monash School of Media, Film and Journalism. Working with them is John Tebbutt, a senior lecturer from the Monash School of Media, and Catherine Strong, a senior lecturer in media and communication at RMIT.

"What struck me moving to Melbourne [from Sydney] was how passionate audiences are here. I can’t give a theoretical underpinning to that. But Melbourne audiences have always been engaged.”

The ’60s also saw the publication of the local music magazine Go Set, and the rise of Melbourne-based TV shows – the hugely popular Go!! Show and Kommotion, both on Channel O (which later became Channel 10). Sadly, most of the footage from the shows has been destroyed, although remnants can be seen on YouTube.

Each of the four researchers on the music project have their own specialty; Dr Homan is known for his research into music policy – he’s looking at the policy settings and conditions that have helped foster the Melbourne music scene.

When he moved to Melbourne in 2009 he “was shocked that no one had written a history of Melbourne music”. “I had written a book about the history of music venues in Sydney, from the ’50s to the 2000s,” he says. “Looking at the Johnny O’Keefe and town hall phases, to the ’60s town hall and early pub scene, to the massive pub-rock era in the ’70s and the ’80s. Then I tracked the decline of that.”

His hope is that the research project will become a book, and possibly a documentary. The team is filming interviews with historic players in the Melbourne music scene – people who participated in important events but aren’t so well known today. They include Marcie Jones, who Dr Homan describes as “an amazing woman who is still singing in her 70s”. She started performing in pubs and town hall dances when she was 15 – the first set would be foxtrots and waltzes, the second half would be pop and rock’n’roll. Then Channel O talent scouts found her and she began appearing on their pop music shows. Another is Bill Amstrong, who started Armstrong Studios in the mid-1960s. “He said he was the first person in Australia to have an eight-track sound mixing desk recorder …If you look at any Melbourne recording from the mid-’60s to the 1980s, he was there,” says Dr Homan.

He says the researchers are interested in the music, genres and scenes, but “also want to tell the larger story. The spine of this narrative is that a music scene doesn’t happen by accident. Yes, you’ll get an upsurge of activity – but what are the conditions that make that activity possible? Is it a change in planning, perhaps? We’re interested in all that stuff as well as the music – we’re trying to meld the two.”

In the 1980s, for instance, the Sydney music scene revived. Sydney became Australia’s creative centre, with international media companies basing their headquarters there. Then the Cain government changed Victoria’s licensing laws in the mid-1980s, sparking a small cultural revolution with compact bars and music venues popping up in city laneways.

Meantime in Sydney, local venues were collapsing. In 1979, 12 people died in a ghost train fire in Luna Park, which led to a state-wide audit of all entertainment areas. New laws, governing fire, noise and licensing were imposed, Dr Homan says. Taken together, they had a chilling effect on the Sydney music scene, as did exploding property prices. Musicians started drifting south again.

Asked if Melbourne music has a particular sound, he says: “There’s something about Melbourne audiences. I was a rock drummer in the ’80s in Sydney, and I played in lots of bands. What struck me moving to Melbourne was how passionate audiences are here. I can’t give a theoretical underpinning to that. But Melbourne audiences have always been engaged.”

He gives the example of the Save Live Australian Music (SLAM) demonstration, held to protect live venues in 2010. “Helen Marcou and Quincy McLean, who run Bakehouse Studios in Richmond, started SLAM and they organised a 20,000-strong march to save live music venues. It went from the State Library to Parliament House. I argued with my Sydney friends that I couldn’t see Sydney organising themselves in the same way, and with the same passion. That made the Brumby government sit up and say, ‘All right, what do you guys really want?’”

The result was the state government’s Live Music Accord, designed to protect live music venues. It has a “first use” clause (that has yet to be tested in the courts), which says that if an apartment block appears near an existing live music venue, the apartment must take responsibility for sound-proofing measures, because the music venue was there first.

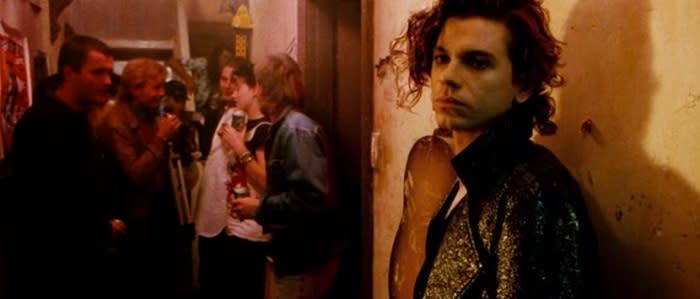

Dr O’Hanlon has a particular affection for the Melbourne punk scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and has written a forthcoming book about it, City Lives (NewSouth). The scene is portrayed in Richard Lowenstein’s feature film, Dogs in Space, and his later documentary about the same era, We’re Livin' on Dog Food. The documentary examines some of the minor characters from an era best known for giving rise to Nick Cave. Singer and guitarist Stuart Grant from the punk band The Primitive Calculators (he’s now a senior lecturer in the Monash Centre for Theatre and Performance) and his fellow musicians were able to survive on the dole, which was then a princely $50 a week. “The state paid us to reject it,” he says.

"The spine of this narrative is that a music scene doesn’t happen by accident. Yes, you’ll get an upsurge of activity – but what are the conditions that make that activity possible?"

The amusing line raises interesting questions about the importance of government support for musicians – and other artists. Punks used to live in Fitzroy and St Kilda, but the once-grungy streets and laneways are now gentrified. Will Melbourne go the way of Sydney, with its lockout laws, which has become too affluent for rock and roll?

Over the past decade or so, the notion of a ‘Music City’ has become a sought-after designation, used to enhance a city’s ‘brand’. On April 19 and 20, Melbourne will host an international Music Cities Convention, to push its case for Music City status. But in the pantheon of UNESCO Creative Cities, Adelaide is Australia’s official Music City, while Melbourne is a City of Literature – according to UNESCO’s rules, the same city cannot be both.

“The state government and the Melbourne City Council see this as an economic plus,” Dr O’Hanlon says. Tourism is part of it – young people are part of it. We don’t make anything anymore; we don’t have any industry anymore. Industry is now culture, and culture is now industry. And that is everywhere – all over the Western world, not only in Melbourne.”

For the time being, at least, Melbourne is managing to support about 500 live music venues, an impressive number for a city of its size. But for how much longer? According to a 2017 report from Music Australia, only 16 per cent of musicians in this country earn more than $50,000 a year (and 56 per cent earn less than $10,000 a year).

Musicians need places to play, and pubs all over the city are being replaced with apartment blocks. Musicians also need places to live. “I’m an urban historian. And what urban historians say is that spaces matter,” Dr O’Hanlon says.

“I think it’s harder for that mid-tier,” says Dr Homan. “For the people who are never going to be recording stars. Up to the mid-’80s I would argue that you could still make a living just playing live, doing some merch, maybe selling some CDs after the show. But it’s now harder for the mid-tier to make a living.”