The world feels a little quieter. Dr Jane Goodall, the primatologist, conservationist, and UN Messenger of Peace, has passed away. For millions, she was an icon. For me, she was a mentor and guide.

Meeting her, I encountered not just a scientist, but a soul of kindness, wisdom, and boundless love for life. She listened fully, smiled gently, and radiated a belief in humanity I will never forget.

Today, the UN family mourns the loss of Dr. Jane Goodall.

The scientist, conservationist and UN Messenger of Peace worked tirelessly for our planet and all its inhabitants, leaving an extraordinary legacy for humanity and nature. pic.twitter.com/C0VMRdKufF— United Nations (@UN) October 1, 2025

My own path to conservation began as a messy, awkward love affair with life itself. I was the child who brought insects to my bedroom similar to how Dr Jane brought wriggling earthworms into bed, both of us more curious than afraid.

I peered at crabs in creeks, though nervous of their pinch. I overturned desert shrubs at night with a torch, finding foxes, beetles and hedgehogs. I devoured Darwin’s writing, lost myself in documentaries, collected specimens, and eventually poured that work into my book, The Year Earth Changed.

Curiosity always came first. Jane often told the story of her own childhood curiosity. She told us that at four, she crawled into a henhouse to wait, four long hours, just to learn where eggs came from. Other parents might have scolded. Hers encouraged. That patience and curiosity created a scientist.

When I first heard her story, I recognised myself in it and I remember thinking, yes, this is the same hunger I felt. That hunger led me to speak at COP28, COY18, TEDx, and to work with Roots & Shoots groups across India and the UAE.

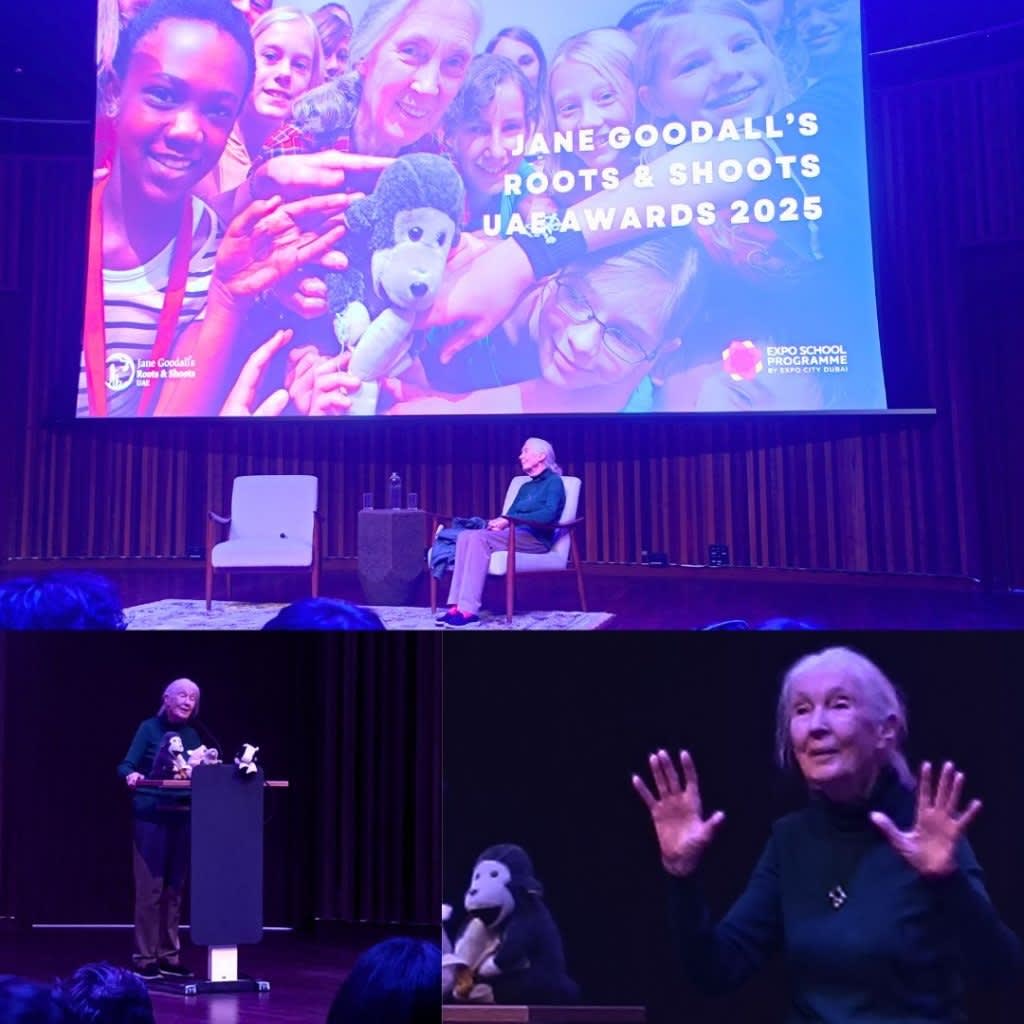

The Expo Terra Pavilion buzzed with energy as students from 12 schools gathered to celebrate Roots & Shoots UAE, a movement Jane started to inspire young people to protect what they love.

She entered quietly, her calm presence commanding attention. When I was introduced to her, my rehearsed lines vanished. I shared my journey, admitting quietly that sometimes the scale of extinctions makes me doubt whether my work matters. She listened fully, her eyes and gentle smile reflecting the patience and connection she once showed chimpanzees at Gombe.

Then she spoke.

“You, young man, are taking Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots around the world.”

Those words landed like a gift and a task all at once. I felt them root inside me. Later, she added to me and to the room, words that have become my armour on hard days:

“With people like you advocating for biodiversity, the future looks bright.”

They were not just words. They were a gift, a charge, and a responsibility. Since then, whenever I lost hope and courage, her voice popped into my head, reignited that flame in me. She showed me that hope is not naive, but a powerful force that fuels action.

I wanted to give her something that spoke beyond words, so I brought a small, delicate gift – a chimpanzee painted on a pheasant feather. The feather, fragile yet carrying the essence of flight and life, symbolised the ecosystems we fight to protect. I painted David Greybeard, her first trusting chimpanzee at Gombe, a reminder of patience, observation, and wonder.

When she held it, she treated it as if it were alive, smiling softly and saying she wanted to take it home, a rare gesture. That moment, knowing something I made had touched her heart, was the most humbling of my life. She also signed my copy of The Book of Hope, a sacred anchor reminding me that hope is not naive but an act of courage, discipline, and practical love.

Our conversation spanned the personal and the global.

She shared how living through World War II showed her that human spirit and leadership can revive hope even in despair, a lesson she carried into her conservation work.

She challenged scientists who dismissed naming chimpanzees, proving through patience that animals feel, mourn, and show individuality.

She spoke of remarkable animals and people – landmine-detecting rats, Pig the painting pig, returning mangroves, and humans overcoming adversity. Even at 91, traveling 300 days a year, she embodied the “indomitable spirit” that kept hope alive through presence and persistence.

And she returned to her refrain, the instruction she passed down to millions of young people:

“Together we can. Together we will. Together we must save the world.”

In October 2024, I led a workshop at the Jane Goodall Institute India, sparking action among young people. With Roots & Shoots UAE, I witnessed small projects with enormous heart – mangrove planting, bee gardens, and educational outreach.

When I told Jane, she smiled and, just before I left for Monash University, invited me to join Roots & Shoots Australia. It was not fame, but trust, a torch passed into my hands.

Jane’s death is a profound loss for science and conservation. She showed that compassion belongs in both the lab and the forest, and that curiosity and persistence can change an entire field.

Her passing is also a summons to act, to mentor, to protect, and to think beyond short-term gain. Her words are not consolation but a charge, one I carry into my studies, podcasts, classrooms and conservation projects, keeping her guidance and spirit alive.

Dr Jane Goodall’s roots run deep, and her shoots now reach farther than she ever could – into classrooms, field stations, mangrove nurseries, and the hearts of young people worldwide who will carry her name forward.

She taught us to listen, watch, wonder, and act. She would not want our grief to end in silence, but for us to transform it into movement – planting trees, protecting forests, rescuing bees and defending life. Hope, she reminded us, is something we create with every act of care.

Goodbye, Jane. The world is quieter without you, but braver and stronger because of you. Your torch burns in our hands, and we will not let it go dark.