Dengue is the world’s fastest-growing tropical disease, with two million people infected each week across more than 100 countries.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito that spreads dengue also carries Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever, infecting about 400 million people a year. The mosquito is active during the day, so the nets that protect sleepers from malaria are powerless against it.

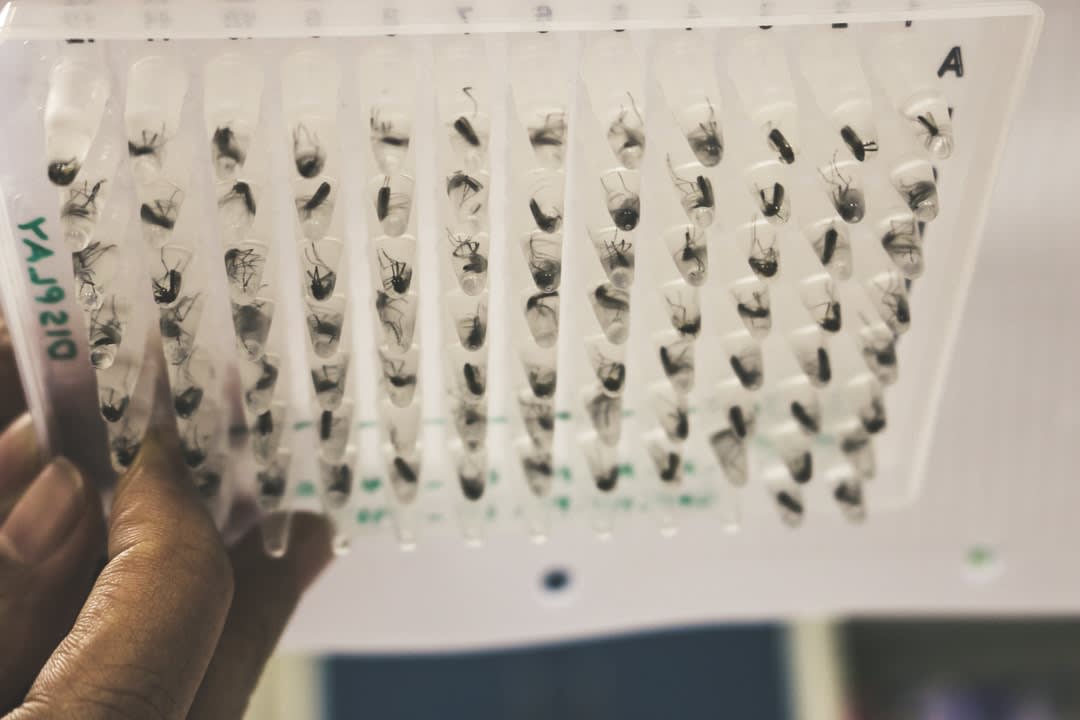

But a common bacterium called Wolbachia that is harmless to humans can stop the Aedes aegypti mosquito from spreading disease. When Wolbachia is introduced into Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, it reduces the ability of dengue and other viruses to replicate in the mosquito and therefore to be passed on.

Scott O’Neill is the Monash-based scientist who discovered the good Wolbachia can do. He also directs the World Mosquito Program, which releases Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into communities that have agreed to the intervention.

The program is now operating in 12 countries around the world – in Australia, the Pacific Islands, Latin America and Southeast Asia. Now, research in Yogyakarta, an Indonesian city where the Wolbachia mosquitoes were released more than two years ago, has confirmed the program’s effectiveness.

The first results of a randomised controlled trial of the Wolbachia method have shown the incidence of dengue is 77% less in those parts of the city where Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes circulate, compared with uninfected areas.

The research, the culmination of a decade of laboratory and field studies, was conducted by the World Mosquito Program and its Indonesian partners, the Tahija Foundation and Universitas Gadjah Mada. The largest trial of its kind was led by Cameron Simmons, Director of the Institute of Vector-Borne Disease at Monash.

"We have evidence our Wolbachia method is safe, sustainable and reduces incidence of dengue. It gives us great confidence for how we can scale this work worldwide across large urban populations." – Scott O'Neill, Director, WMP

Professor Simmons, who is also the Oceania director of the World Mosquito Program, described the result as “incredibly exciting”, and “just what the global community needs”.

It demonstrates that the Wolbachia method can be scaled across a large urban setting, and has huge potential for large cities in the tropics where dengue is endemic.

The program aims to protect 100 million people from mosquito-borne diseases by 2023.

“This is the result we’ve been waiting for,” Professor O’Neill says. “We have evidence our Wolbachia method is safe, sustainable and reduces incidence of dengue. It gives us great confidence for how we can scale this work worldwide across large urban populations.”

The Yogyakarta result also illustrates the importance of community support, which has been central to the program from its inception.

“We have always, in all our work, indicated that if communities are not accepting of it, then we will not push it on to people,” Professor O’Neill says.

This means that about a quarter of the program’s budget “or more” is spent on community engagement.

“If you’re starting from the premise that you will only do work if the community accepts it, then the onus is on you to engage the community and get the acceptance,” he says.

The principle is worth bearing in mind as politicians and medical experts debate the ethics of making a future COVID-19 vaccine compulsory.

Interestingly, in the early days of the World Mosquito Program, Yogyakarta was the only city where a small number of people organised to reject the intervention. (Indonesia was the third country where Wolbachia-implanted mosquitoes were released.)

Read more: A breakthrough in reducing mosquito-spread diseases with Wolbachia

Yogyakarta has 38 universities, and an “amazing number of students and academics”, Professor O’Neill says. “So, people there are maybe more questioning than in other communities.

“One university academic was fairly critical of what we were doing … so we didn’t release our mosquitoes in one area. Interestingly, some years later, the community asked us to come back and do the releases. The opposition was fairly short-lived.”

In the trial, 12 of 24 areas of Yogyakarta were randomly chosen to receive Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in addition to routine dengue control measures – these “vector control” strategies target mosquitoes and their breeding sites, and involve pesticides. The approach has failed to stop disease transmission in almost all countries where dengue is endemic.

The trial area contained about 312,000 people. The remaining 12 areas continued to receive the vector control treatments only.

The trial also enrolled 8144 participants aged between three and 45, with acute fever lasting one to four days, who attended one of 18 clinics. The research measured how effective the Wolbachia intervention had been in reducing dengue cases over 27 months.

Listen to Monash Vice-Chancellor Margaret Gardner's message of support for the World Mosquito Program's work

The World Mosquito Program’s Director of Impact Assessment, Katie Anders, said: “This is the first trial of an intervention against the dengue mosquito to demonstrate an impact on disease incidence.

“The trial result is consistent with our findings from previous non-randomised studies in Yogyakarta and northern Queensland, and with epidemiological modelling predictions of a substantial reduction in dengue disease burden following Wolbachia deployments.”

Dengue thrives in urban environments. It's expanding rapidly, and threatens almost half the world’s population. In 2019, the World Health Organisation declared it one of the top 10 global health threats.

Mild cases typically present with fever, lethargy, headache, nausea and rash for five to seven days. More severe cases may present with severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, rapid breathing, bleeding and vascular leakage.

Severe dengue is a leading cause of serious illness in some tropical countries, requiring intensive care.