Predictive data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) and automated decision-making (ADM) are gradually, almost unnoticed, entering the vocabularies of our news, and becoming part of our everyday lives.

They arrive through the technologies we already use in our mundane and necessary activities, and become part of daily routines without us even noticing them. As this happens in our quotidian worlds, the realities of emerging technologies come about as mundane, boring and seemingly of little consequence.

Yet the emergence of some new technologies remind us of the spectacular anxieties and hopes of science fiction, and generate public fantasies of futures where technologies will dramatically change the ways we live and feel.

The question of autonomous vehicles

Self-driving cars have inhabited our popular imaginations for decades, and are the perfect example of how unrealistic the popular and policy imaginations of our technological futures can be, and why we need rigorous research into how such technologies could really become part of the lives of people and societies.

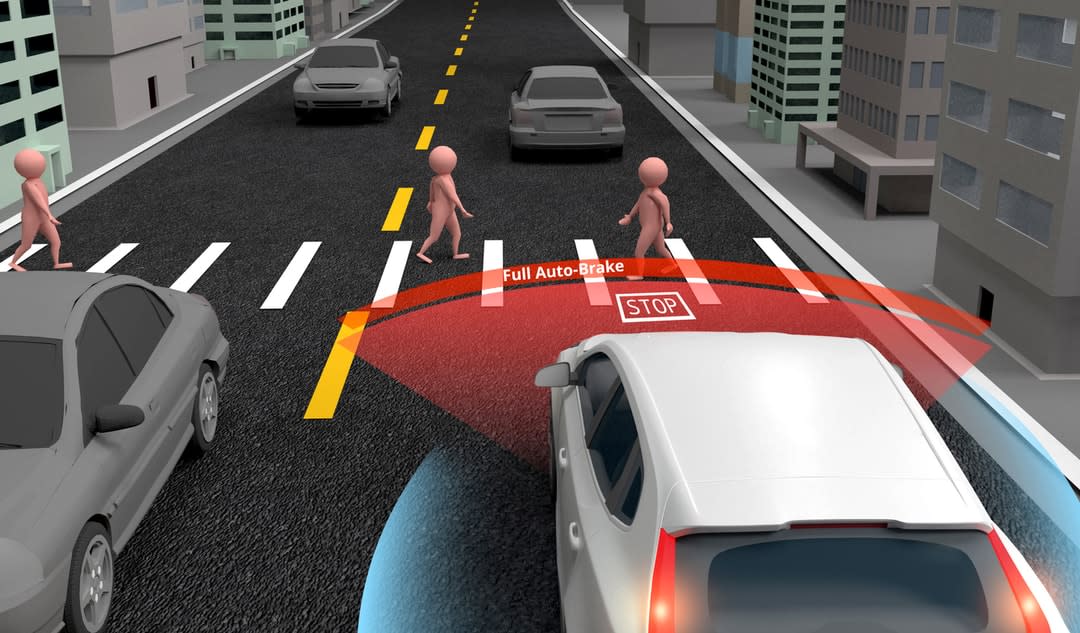

In 2015, self-driving cars were said to have been the most-hyped emerging technology, and continue to be in the news every day. They're commonly associated with bright utopian futures, where they're seen as a technologically-driven solution to problems such as reducing carbon emissions and road safety, as well as promising to free up drivers’ time for other activities.

Self-driving cars will also be capable of collecting, producing and using significant amounts of data about us, will enable machine learning that could improve our experience of being in vehicles, as well as having predictive capabilities in the organisation of our travel and our everyday lives.

On the darker side, however, self-driving cars are seen by some as raising issues of safety – the safety of our personal data, and our personal safety. In accident scenarios, they say, artificial intelligence might use our data to determine who is of most value to those who are powerful in society, and who to save based on the value attributed to individuals through data analytics.

Of course, along with the hype is sensationalism. News is much more enticing when we're presented with the threat of a robot-car deciding whose life to take, instead of discussing the more plausible widespread futures of the boredom of the everyday commute, which is where self-driving cars are actually likely to have much more significance in our lives.

Shaping a more plausible future

But the more deeply rooted problem is that the fundamental beliefs that inform this hype and sensationalism are based on simple assumptions, and not on rigorous research into how people really live with technologies in everyday life, or on social scientific understandings of the societal problems that frame the fear that future self-driving cars will kill us.

This is why it is so important that our research into what data really means, and how to shape our future lives with artificial intelligence, machine learning and automated decision-making, accounts not simply for the possible utopian or dystopian impacts that these technologies could have on society, but that it also accounts for what people’s future needs will be, and how emerging technologies such as self-driving cars can be designed to be most useful to us.

To do this I develop, with teams of researchers, design anthropology techniques. This method is much deeper than superficial surveys and questionnaires, because it means we can get under the surface of human life, experience and imagined futures to gain knowledge about what's really happening and what plausible futures might look like.

Their entry into our future lives won’t be sensational; rather, it will be quite mundane and boring.

To ensure that self-driving cars and other emerging technologies are safe, we need to attend to societal questions – to questions of regulation and governance in terms of how data is used.

Self-driving cars won’t kill us; rather, the societal power relations and inequalities that already exist, and already make some people’s life expectancy shorter than that of others, are what will be responsible for any deaths that were to happen in such circumstances.

To know how to make emerging technologies safe and equitable, we require knowledge concerning how personal and machine data can be given plausible meaning, how it can effectively engage with everyday life as lived to the benefit of real people living in specific circumstances – with the why and the how, as well as what can be measured.

Self-driving cars won't save the future world from anything. That will be down to how people fit them into their lives and how they become part of future wider mobility systems. Humans might use self-driving cars to improve aspects of our future lives, but the changes will be driven by people, not the technology.

In fact, when we consider what self-driving cars will be used for – part of people’s everyday commutes to work, taking the kids to sports clubs after school, doing the grocery shopping – it's hard to understand why there's so much hype. Their entry into our future lives won’t be sensational; rather, it will be quite mundane and boring. How your car picked up your weekly shop of breakfast cereals, toilet paper and pasta, or the first kilometre of your daily commute, isn't exactly what you’ll want to chat about to impress professional colleagues or new friends.

All of these ways that self-driving cars might come into our future lives is, however, fascinating for social researchers from two perspectives.

First, because as academics we're not just interested in self-driving cars; they're an example of a technology that helps us to learn about the evolution of the relationships between people AI, ADM and machine learning, and helps us to better understand how we need to shape our human futures with technologies.

At the same time, social research in this field means we can collaborate in the technological research and design of self-driving cars in such a way that acknowledges how they'll fit into life itself, as well as the continually evolving landscape of emerging mobilities technologies, services and more.

The case of self-driving cars shows clearly that we need to move away from the idea that research and design of emerging technologies is simply an engineering or IT problem. It raises questions that need to be addressed from the perspective of the social sciences, design, policy and governance, and business disciplines. This, of course, is a lesson for all research into our futures with data, AI, ADM and ML, so that we can come together, across our disciplines, to create better, more equitable and more responsible futures.

Interdisciplinary approach

The Emerging Technologies Research Lab at Monash University is committed to these principles. We focus on the social, cultural and experiential dimensions of existing and future emerging technologies, including future mobilities technologies, energy technologies, digital health, personal data, and the problem of e-waste – frequently through interdisciplinary collaboration.

We're passionate about ensuring that our future shared environments – with technologies, other species and other future things – are ethical, equitable, sustainable and safe.

With our colleagues at Halmstad University and Volvo Cars in Sweden, we've been researching human experience and expectations of self-driving cars and future mobility systems for the past four years. Our international collaboration makes us the first academic-industry research group in the world to have pioneered design anthropological research in this area.

Through Monash Data Futures, we’re investing in applied AI as a force for social good.

Find out more about this topic and study opportunities at the Graduate Study Expo