Monash University’s Associate Professor Sanjiva Wijesinha served as a doctor in two defence forces for a combined 30 years – in the Sri Lankan Army’s Medical Corps (for his home country), and then in the Royal Australian Army’s Medical Corps. He's interested in defence forces and mental health – particularly the question of how to transition from military to civilian life.

Early in April, Dr Wijesinha, from Monash’s Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, packed his stoutest walking shoes and did what he often does – a pilgrimage walk. This month it was the 88-temple trail on Japan’s smallest island, Shikoku.

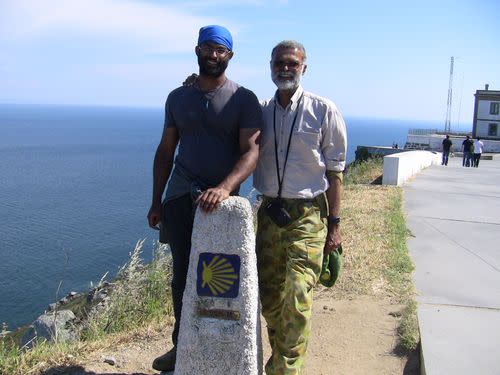

Dr Wijesinha practises what he preaches; he says former soldiers and military personnel can find an immense sense of meaning from pilgrimage walks, and he regularly does them himself, particularly the renowned 800-kilometre Camino de Santiago trail in northern Spain.

Dr Wijesinha, along with his Monash role, is also a Melbourne GP and writer – he’s written books on travel and health, as well as fictional short stories. He's written a book on walking the Camino with his son, titled Strangers On The Camino.

“Transitioning from service in the military back to civilian life can be an extremely challenging period,” he writes in a new article based on a 2017 speech to the Australasian Military Medical Association. It can “precipitate the onset or exacerbation of mental health problems”.

He argues that a pilgrimage, a “journey of spiritual healing”, even for a secular ex-soldier and “undertaken in the company of like-minded companions”, can be “one way of helping veterans through this particularly vulnerable transition period”.

He cites the book A Soldier to Santiago by a US Navy veteran, former senior chief petty officer Brad Genereux, who wrote: "For over 22 years and with pride I represented my country by wearing the uniform of my nation. And when my service was all over? Life had passed me by and I found that I fit in – nowhere."

Genereux founded a group called Veterans on the Camino, a project aimed at helping military veterans having problems transitioning back to civilian life by taking them over the Camino trail to the shrine of the Apostle St James the Great in a cathedral in Galicia. It's a Christian pilgrimage dating to the Middle Ages; now it attracts (on various routes) hundreds of thousands of Christians and others on foot or on bike every year.

Dr Wijesinha writes that for some ex-military people a pilgrimage can help mental health for the following reasons:

IDENTITY

Leaving behind a military uniform and the status that it brings can be “profound”. The soldier or serviceperson becomes just another civilian with nothing to set him or her apart. A pilgrimage can essentially be a reinvention.

TRADITION

Like military service, a pilgrimage is steeped in thousands of years of tradition, rules and ritual.

ACTION

Soldiers execute planned missions. So do modern-day pilgrims – “a shared direction of movement toward a common end”.

COMMUNITY

“Walking in a community of others who are on a similar quest and so becoming part of a community brings about a sense of mutual respect,” Dr Wijesinha writes.

He recognises that walking on a pilgrimage won't help all ex-military people with poor or potentially poor mental health. But he says for some it could be very helpful, and even a lifesaver.

Dr Wijesinha cites data from two major studies into the mental health of ex-military personnel. Last year's Department of Defence and Department of Veterans' Affairs Mental Health and Wellbeing Transition Study outlined that the move from military to civilian life was “significant and stressful” worldwide because of identity crises, changes in community and living arrangements, social networks and status, family, work, money, routines and new responsibilities.

The study showed that Australian Defence Force (ADF) members transitioning back to civilian life would benefit from “proactive strategies” to lessen the mental health burden. It estimated 46 per cent of ADF members transitioning in the previous five years met the diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder.

Read more Hope for thousands with PTSD

In 2017, in the second study cited, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare released a specific report on suicide among serving and ex-serving ADF personnel. Those studied had served between 2001-2005. It found the suicide rate of ex-serving men was more than twice as high as serving men and 14 per cent higher than non-military men. He says there was scant data on women in the report.

“It's not unreasonable to speculate that such a high rate of suicide in Australian [male] veterans after they're discharged from the ADF indicates a high rate of mental illness in this population,” Dr Wijesinha writes.

He says ex-soldiers can lose self-respect, stability, status in society (“they virtually become nobodies”), and have to start their lives again.

Embarking on a pilgrimage, he says, can bring back “joy and comradery ... the world and its travails seems a thousand miles away. One feels so very small, and yet one feels part of humanity – and a part of the universe.”