In recent years, AI-generated deepfake technology that can convincingly replace one person’s likeness with another has evolved from a technical curiosity into a powerful tool for abuse.

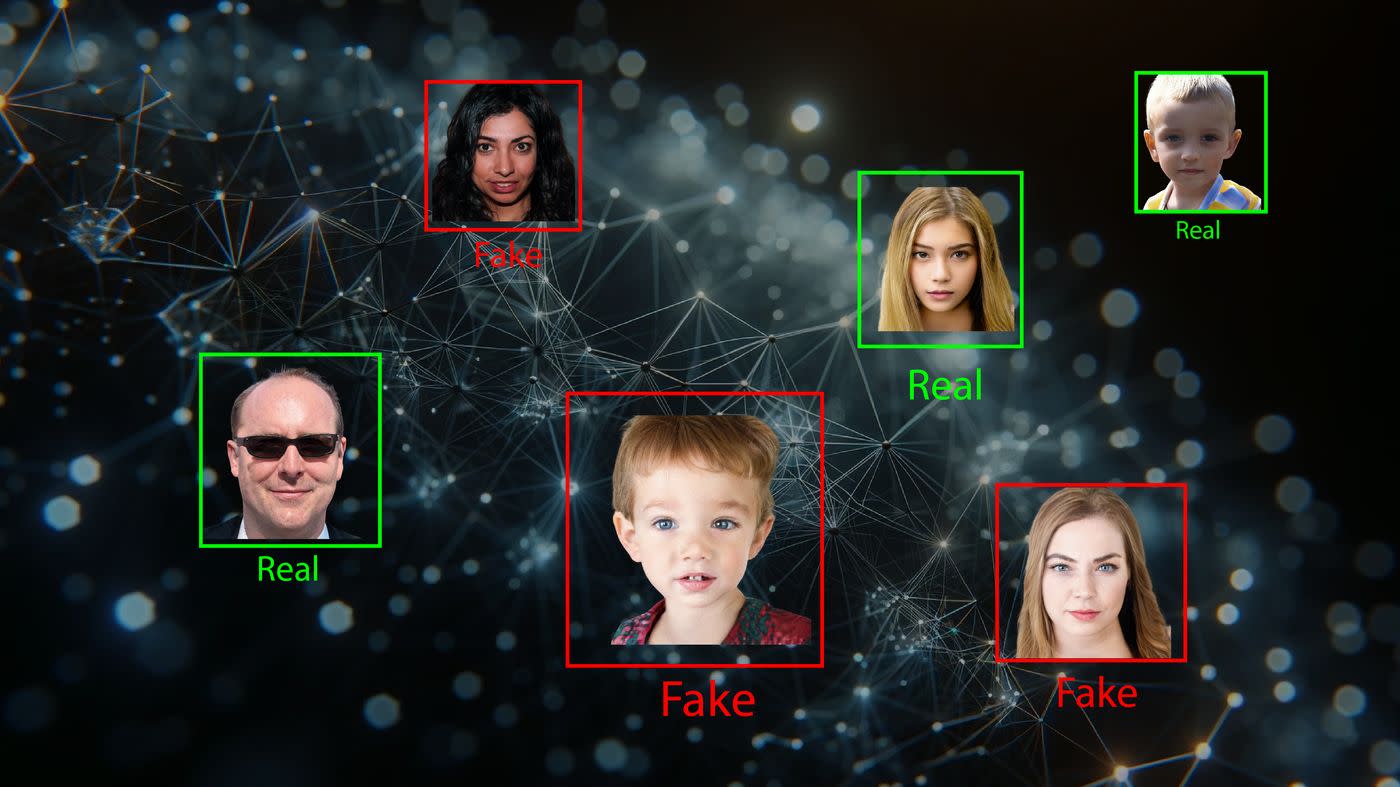

Once requiring specialist knowledge and expensive software, these tools are now widely available through free or low-cost online platforms and mobile apps.

This accessibility has dramatically increased the potential for misuse, particularly in the form of sexualised deepfake abuse, where non-consensual pornographic, nude or sexualised imagery is created or circulated using real people’s faces.

Victims range from celebrities to everyday individuals, particularly young women, who have been digitally “nudified” or inserted into explicit videos without consent.

It’s now recognised as one of the fastest-growing forms of technology-facilitated gender-based violence, intersecting with issues of privacy, consent and digital ethics.

Experts warn that the rapid normalisation of these practices, often trivialised as jokes or internet “experiments”, is eroding social norms regarding respect and accountability, while legal systems struggle to keep pace with the technology’s reach and sophistication.

Perpetrators’ motivations examined

Against this backdrop, a research team led by Monash University has, for the first time, interviewed the perpetrators of sexualised deepfake abuse to examine their motivations.

The research is published via open access in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence, and addresses the increased accessibility of AI tools to help create realistic and clearly harmful non-consensual fake sexualised imagery. It also considers the regulations on the marketing of AI tools and laws regarding sexualised deepfake abuse.

The study’s lead author is Professor Asher Flynn, a globally-recognised criminologist and social scientist specialising in the nexus between sexual abuse and technology. She’s from the School of Social Sciences and is also Chief Investigator on the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (CEVAW).

The research, which also included interviews with victims of sexualised deepfake abuse, is funded by the Australian Research Council.

Sharing encouraged for ‘status’

Professor Flynn says creating and sharing sexualised deepfake imagery is not only normalised among some young men, but encouraged as a way to bond or gain status. The study found that male perpetrators tended to downplay the harms caused, and they shifted the blame away from themselves to instead focus on how rapidly-escalating AI technologies made the images easy to create and experiment with.

“There’s a clear disconnect between many of the participants’ understanding of sexualised deepfake abuse as harmful, and acknowledging the harm in their own actions,” Professor Flynn says.

“Many engaged in blaming the victim or the technologies, claiming their behaviour was just a joke or they outright denied the harm their actions would cause – echoing patterns we see in other forms of sexual violence both on and offline.”

She says the new generation of AI tools, “combined with the acceptance or normalising of the creation of deepfakes more generally, such as FaceSwap [where you swap your face onto a celebrities’ body or vice-versa] or other tools considered harmless or ‘fun’, gives access and motivation to a broader range of people, which can also have the effect of weakening deterrent effects or interventions”.

The rise of deepfake imagery

The paper explains that sexualised deepfake imagery first emerged in 2017 on Reddit when a user uploaded fake imagery they had non-consensually created with female celebrities’ faces transposed onto the bodies of pornography actors. Since then, there’s been a growing number of websites and digital platforms becoming available that provide the resources and tools for users to create fake imagery of a sexual nature.

Further, it describes both free and pay-to-use “nudify” apps that can create a sexualised deepfake using any image, simply by digitally erasing the person’s clothing.

The paper looks back on the past 12 months where there have been substantial increases in reports of sexualised deepfake abuse globally, including high-profile celebrities (such as Taylor Swift), as well as incidents involving schoolgirls and female teachers. Recently in Sydney, police began investigating reports of deepfakes using the faces of female students from a high school that were circulated online.

In addition to exploring why perpetrators say they’re engaging in these behaviours, the study contributes new knowledge on the nature of sexualised deepfake abuse and the effects on victims.

The researchers interviewed 10 perpetrators and 15 victims in Australia. Despite the severity of the harm, none of the perpetrators interviewed had faced legal consequences. Victims also reported little to no recourse – even when incidents were reported to police. The paper has two primary questions:

- What types of sexualised deepfake abuse behaviours are engaged in and experienced in Australia?

- What are the self-disclosed and perceived motivations of sexualised deepfake abuse perpetration, as identified by perpetrators and victims of sexualised deepfake abuse?

The study found four forms of sexualised deepfake abuse, including non-consensually creating, sharing, threatening to create and threatening to share sexualised deepfake imagery.

All 10 perpetrators reported having engaged in both the creation and sharing of images. “Sharing” here means sent directly to the victim, to family or friends, sharing the imagery within chat groups (such as WhatsApp) or via Air Drop, and distributing the imagery on platforms such as Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook Messenger, Telegram and dating apps including Grindr. One perpetrator printed images on t-shirts.

In some instances, the study found images were shared (uploaded) on pornographic websites, in addition to being shared in private messaging groups.

The four perpetrator motivations identified included monetary gain (sextortion), curiosity, causing harm, and peer reinforcement. Describing his motivations to the researchers, one perpetrator expressed a desire to gain affirmation and acceptance from his peers:

“They say, ‘Wow, that’s awesome’. You know, like, they were in awe. ‘How’d you do that?’ It was more self-pride in the image more than anything, like, we weren’t, you know, anti-women … No-one said, “Don’t send that’. It was more, like, it was accepted behaviour.”

A clear theme of the paper was the “disconnect” between participants’ understanding of sexualised deepfake abuse as harmful and acknowledging their own behaviour as harmful.

“Participants would commonly minimise or deny the injury or harm to the victim in their experience, even when acknowledging that the behaviour could be problematic in other contexts,” the paper says.

This “neutralisation” of behaviours was expressed by both perpetrators and victims, “suggesting that minimisation was both a justification technique and a coping mechanism (potentially to reduce stress and maintain control)”.

The paper concludes that there’s a need for responses that recognise the accessibility and ease with which deepfakes can be created, which means looking beyond only responding with laws that criminalise individual behaviours to also consider how we can shift social norms that accept this behaviour or undermine its harms, and that more broadly regulate deepfake tool availability, searches and advertisements.